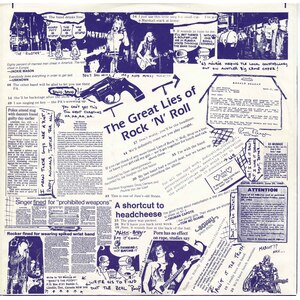

London Underground

London Underground documents one of the most complete and continuous regional music records in Canada, tracing how a mid-sized Ontario city developed its own recording culture over more than a century, from the early twentieth century to the present day. Spanning orchestral dance music, early rockabilly and pop, garage and R&B, private-press rock, experimental and electronic music, funk, soul, hard rock, proto-punk, punk, post-punk, alternative, and independent rock, the archive shows how London functioned as a self-contained musical ecosystem with its own musicians, studios, venues, radio infrastructure, educational programs, manufacturing, publishing, and civic memory, as well as record labels from 1900 through 2025.

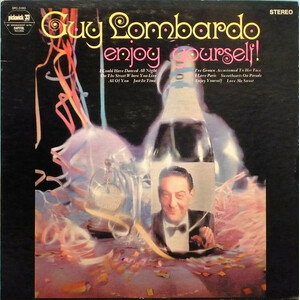

That continuum begins well before rock ’n’ roll. London was the birthplace of Guy Lombardo (born 1902), one of the most successful bandleaders in North American popular music and a pioneer of large-scale recorded and broadcast dance music. Long before independent labels, radio compilations, or underground scenes, Lombardo’s early musical formation in London led to an international recording career that helped define the sound, structure, and commercial reach of twentieth-century popular music. His success represents one of the earliest examples of a London-born artist shaping recorded music far beyond the city’s borders — and establishes London’s connection to recording history at the very start of the modern music industry.

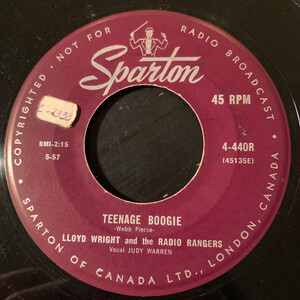

By the 1930s, London was also home to Sparton Records of Canada, one of the most important early industrial pillars of Canadian recorded music. Founded in London in 1930, Sparton became a major manufacturer and distributor, pressing records for labels such as Columbia while also issuing its own catalogue. Although Sparton functioned primarily as a national production and manufacturing centre, its London operation was closely tied to Ontario’s broadcast and community-based music culture, releasing recordings by local artists including Priscilla Wright, Don Wright, and Lloyd Wright and the Radio Rangers, Southwestern Ontario performers such as Guelph’s Velvetones, Cliff McKay, and Ward Allen, and Toronto-area folk, country, and popular acts including Bob Scott and the Canadian Pioneers, the Travellers, the Happy Wanderers, the Rhythm Pals, and the Starlighters. Sparton was also the first company in Canada to manufacture stereo records, and its presence placed London at the centre of Canadian record production decades before the rise of independent rock labels or underground scenes.

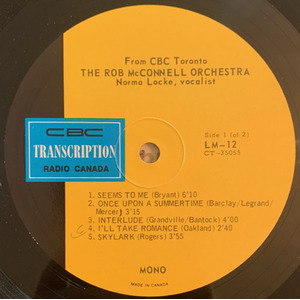

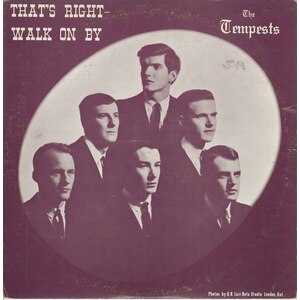

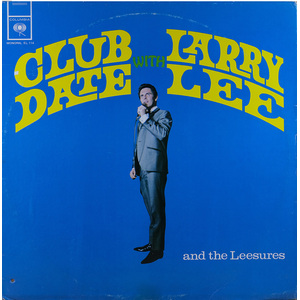

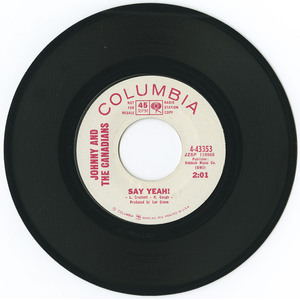

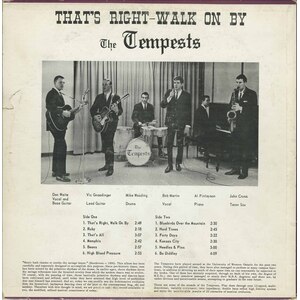

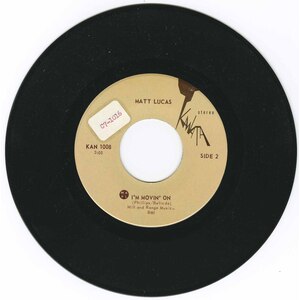

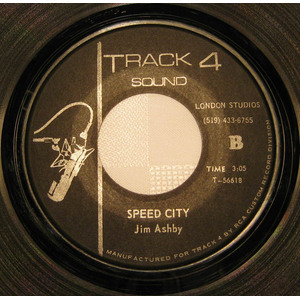

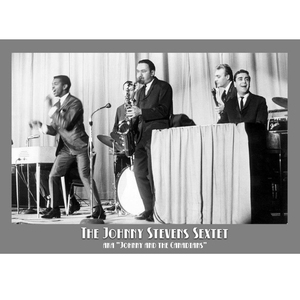

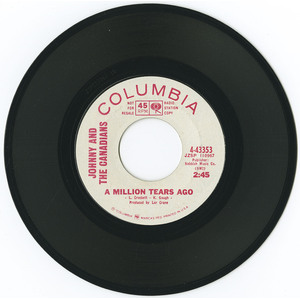

London’s modern recorded history began in earnest in the mid-1950s. Artists such as Priscilla Wright and Lloyd Wright and the Radio Rangers were already recording professionally, supported by CFPL radio and television and a local broadcast culture that actively generated recorded output. By the early 1960s, the city was producing full-length albums and singles by acts like Larry Lee & the Leesures, The Tempests, Ronnie Fray and the Versatile Capers, and Johnny and the Canadians — groups that toured widely, appeared on national bills, and left behind recordings that now stand among the strongest documents of early Canadian rock ’n’ roll, rockabilly, R&B, and garage music.

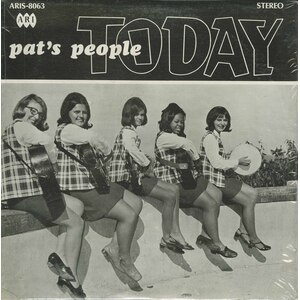

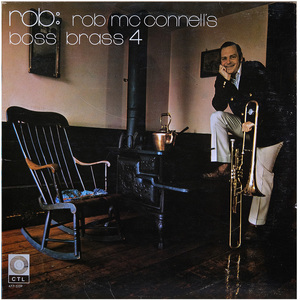

The late 1960s and 1970s saw London broaden stylistically rather than narrow, as funk, soul, jazz-rock, hard rock, and progressive approaches emerged alongside earlier forms within an increasingly album-oriented local scene. This period of expansion coincided with the presence of GRT of Canada, the Canadian arm of General Recorded Tape, which operated out of London in the early 1970s and briefly placed the city inside the national recording industry. During this window, London-origin recordings by Thundermug, Truck, Canadian Conspiracy, and singer-songwriter James Leroy moved from local production into national distribution, while the same London-based GRT operation also handled major Toronto and regional acts including Klaatu, Lighthouse, Dr. Music, and Hamilton’s Grant Smith & The Power, situating London at the intersection of local creativity and Canada’s commercial recording infrastructure.

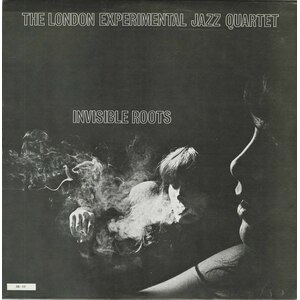

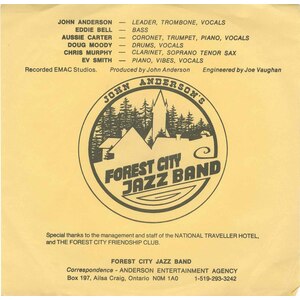

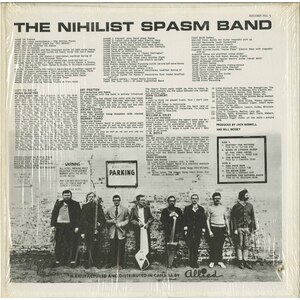

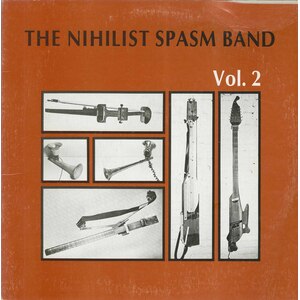

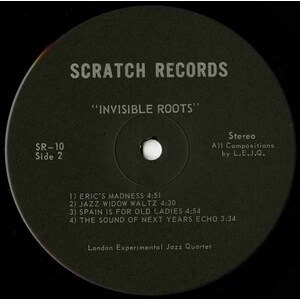

At the same time, London became home to some of the most radical experimental music in the country. The Nihilist Spasm Band — active from the mid-1960s onward — established an internationally recognized free-improvisation practice rooted entirely in London, releasing records, building custom instruments, and proving that the city could sustain long-term avant-garde activity independent of commercial pressures. Groups such as the London Experimental Jazz Quartet further document this parallel experimental lineage, operating alongside — not outside — the city’s broader recording culture.

This same locally rooted ecosystem also extended beyond records and clubs into national broadcast. Running parallel to underground and album-oriented growth, London-born Tommy Hunter became one of the most influential figures in Canadian broadcast music, hosting The Tommy Hunter Show from 1965 through 1992 and using national television to elevate country, folk, and popular music performance standards while launching and supporting generations of Canadian artists.

This experimental and technical current extended into academic and studio contexts. Fanshawe College emerged as a key site for electronic and studio-based experimentation, guided in part by producer Jack Richardson, who helped connect training to industry-level practice. Richardson — best known for producing landmark recordings by The Guess Who, Alice Cooper, Bob Seger, Kim Mitchell, Diana Krall, and later receiving Producer of the Year recognition for work associated with Alanis Morissette and A Tribe Called Red — played a crucial role in connecting London’s training environments to the highest levels of international recording practice.

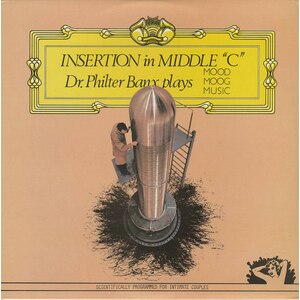

Projects such as Dr. Philter Banx’s 1975 Moog-based LP, created by Fanshawe students working within one of Canada’s earliest post-secondary electronic music programs, were not anomalies. They were direct products of a functioning, locally rooted recording environment that encouraged experimentation alongside professional discipline.

London’s experimental lineage continued into electronic music through figures such as John Acquaviva, whose early work as a DJ, tastemaker, and studio collaborator was grounded in London. Before co-founding the internationally influential Plus 8 label, Acquaviva operated out of London, linking the city’s existing culture of experimentation to Detroit techno and extending London’s underground tradition into new technological forms rather than breaking from it.

London’s continuity is also reflected in artists whose careers bridged local beginnings and national success. Doug Varty emerged from the London scene through early groups such as Homestead and Southcote before charting nationally with Sea Dog and later Lowdown. Other artists with formative London roots include Garth Hudson of The Band, whose early musical development began in the city. Justin Bieber, also born in London, represents a later global extension of this pattern, demonstrating how London-origin artists have continued to shape popular music across eras.

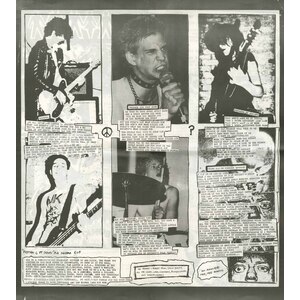

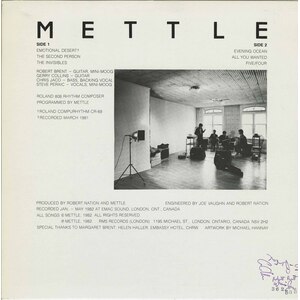

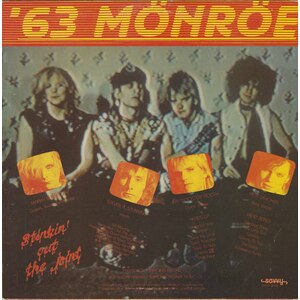

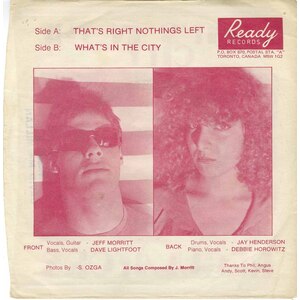

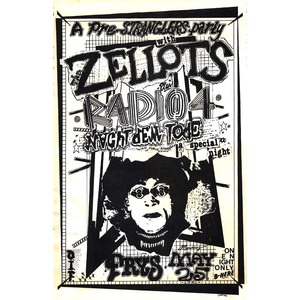

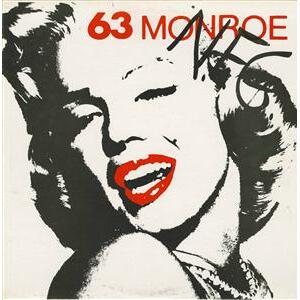

By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, London became one of the most thoroughly documented punk and post-punk centres in the country. Nationally visible releases by Demics and ’63 Monroe sit alongside independent recordings by Crash 80’s, Sheep Look Up, Mettle, Second Thoughts, The Regulators, Conning Tower, The Hippies, Generics, Friendly Fire, and others. These artists operated within an active local circuit supported by venues, print culture, independent labels, and — critically — CHRW Radio Western, whose broadcasts and compilations preserved an extraordinary amount of material that might otherwise have disappeared.

CHRW’s role cannot be overstated. From early cassette and vinyl compilations through later CD projects, the station provided both exposure and documentation, capturing punk, alternative, experimental, and independent music as it happened. Releases such as The 1990 London Compilation, London Underground, and later CHRW projects show a city still recording, still organizing itself, and still leaving a clear historical trail. Animals Fight Back, issued by Yeah Right! Records, stands as a key example — linking local bands, radio, and independent production within the same ongoing network.

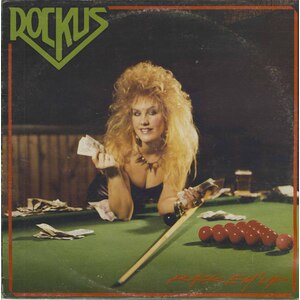

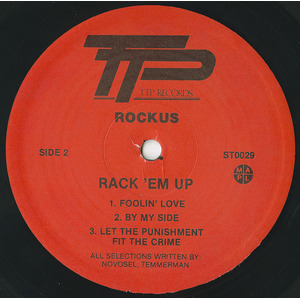

Throughout this period, London sustained its own independent labels and producers, including Auto Records (Peter Brennan), Jaymar Music (publishing), Raven Records in the 1990s, and Yeah Right! Records, creating release pathways that did not depend on outside industry centres. Yeah Right! remains active today, continuing to produce and support London-area artists and reinforcing the city’s long-standing independent label tradition.

This recorded legacy is now also reflected in formal music-specific preservation. The London Music Hall of Fame has documented and celebrated the city’s musical history through curated displays and permanent artifacts honoring artists with deep London ties, including Guy Lombardo, Tommy Hunter, Don and Priscilla Wright, Garth Hudson, Thundermug, ’63 Monroe, Sheep Look Up, and later generations such as Kittie. By presenting physical evidence of recorded and performed music across eras, the Hall of Fame reinforces London’s long-standing role as a place where musical activity was not only created and recorded, but remembered, contextualized, and publicly acknowledged.

Thanks are due to John Berkmortel (Gilded Cage) for his inspiration, materials, and long-standing documentation of the London scene, and to Peter Brennan, whose work as a musician and label operator helped shape the city’s independent recording history.

Taken as a whole, London Underground is a regional archive that shows how music was written, recorded, manufactured, circulated, broadcast, preserved, and institutionalized locally for more than a century. Few Canadian cities outside the largest centres can be reconstructed with this level of specificity. The records exist. The documentation exists. And thanks to sustained local and civic effort, so does the history — now gathered in one place at citizenfreak.com.

-Robert Williston

Notable omissions

This overview emphasizes London’s recording ecosystem rather than assembling a comprehensive list of London-born musicians. As a result, several important figures are omitted intentionally rather than by oversight.

Paul Pesco was born in London, Ontario, and went on to become one of the most successful Canadian-born session guitarists internationally, performing on major recordings by Madonna, Whitney Houston, Sting, Steve Winwood, and others. Pesco’s professional career unfolded almost entirely outside London, and his omission reflects the essay’s focus on locally rooted recording activity rather than later global careers. If included, he would logically belong alongside artists such as Justin Bieber as an example of London-origin talent whose impact was realized elsewhere.

Tom Wilson, the influential producer behind landmark recordings by Bob Dylan, the Velvet Underground, and Frank Zappa, was born in Wingham, Ontario, and maintains indirect ties to Southwestern Ontario through projects such as Central Nervous System and the Pepper Tree lineage. While his historical importance is unquestioned, including Wilson risks shifting the focus away from London itself, and his omission reflects a deliberate effort to keep the narrative geographically precise.

No Comments