Information/Write-up

Guy Lombardo was one of the most successful, influential, and enduring bandleaders in North American popular music, a Canadian-born musician whose polished orchestral sound helped define mainstream dance music from the 1920s through the early television era. Though often associated with American popular culture, Lombardo was born Gaetano Alberto Lombardo on June 19, 1902, in London, Ontario, the eldest of seven musically gifted siblings raised in a disciplined Italian-Canadian household where music was both a vocation and a family enterprise.

Lombardo formed his first band in his teens, initially playing local dances and social functions around southwestern Ontario. In 1924, Guy and his brothers—Carmen Lombardo (saxophone), Lebert Lombardo (trumpet), and Victor Lombardo (saxophone)—officially organized Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians, a name chosen to emphasize both their Canadian identity and the refined image they wished to project. Unlike the hot jazz styles emerging at the time, Lombardo cultivated a smooth, tightly arranged dance orchestra sound that emphasized melody, clarity, and ensemble precision.

The band relocated to the United States in the mid-1920s, securing a long-term residency at the Roosevelt Grill in New York City. Their breakthrough came with a series of hit recordings for Brunswick Records, including the era-defining “Charmaine” (1927), which sold millions of copies and established Lombardo as a national figure. While jazz purists often dismissed the Royal Canadians as overly polished, their appeal to mainstream audiences was enormous, particularly among dancers and radio listeners.

By the early 1930s, Guy Lombardo had become one of the highest-paid bandleaders in America. His orchestra was a fixture on radio, and their New Year’s Eve broadcasts—first from the Roosevelt Grill and later from venues such as the Waldorf-Astoria—became a cultural institution. Lombardo’s association with “Auld Lang Syne”, which he performed annually at midnight on December 31, permanently linked his name with New Year’s celebrations across North America. Though he did not popularize the song originally, his broadcasts effectively made it the modern soundtrack of New Year’s Eve.

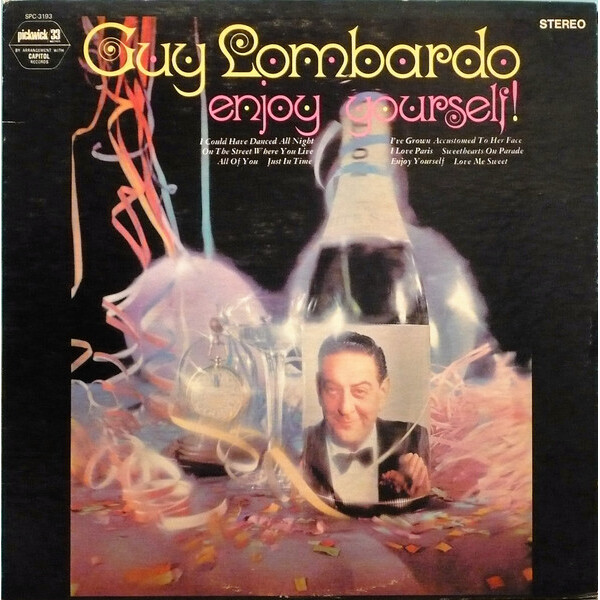

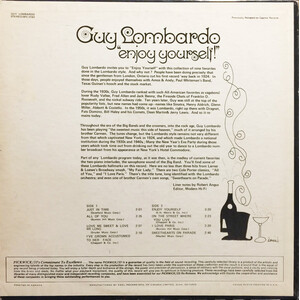

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the Royal Canadians recorded prolifically and scored numerous hits, including “Seems Like Old Times,” “Blue Skies,” “Moonlight Serenade,” “Harbor Lights,” and “Enjoy Yourself (It’s Later Than You Think).” Lombardo’s approach emphasized strict tempos, lush reed sections, and meticulous arrangements—often credited to his brother Carmen—creating a recognizable “sweet band” sound that stood in contrast to swing-era jazz orchestras led by figures such as Benny Goodman or Count Basie.

Despite shifting musical tastes after World War II, Lombardo adapted successfully to new media. He became a regular presence on television in the 1950s, hosting and appearing on variety programs and continuing his annual New Year’s Eve broadcasts, which transitioned seamlessly from radio to television. The band also maintained a heavy touring schedule, performing in ballrooms, hotels, and concert halls well into the rock ’n’ roll era.

Beyond music, Guy Lombardo was a passionate hydroplane racing enthusiast and team owner, achieving significant success in the sport during the 1940s and 1950s. His involvement in powerboat racing became a secondary public identity, reinforcing his image as a disciplined competitor both on and off the bandstand.

Guy Lombardo remained active as a performer and bandleader into the 1970s, eventually passing leadership of the Royal Canadians to his brothers and later family members. He died on November 5, 1977, in Houston, Texas, following heart surgery.

Though sometimes underestimated by critics focused on jazz innovation, Guy Lombardo’s cultural impact is indisputable. He helped standardize the sound of modern ballroom music, pioneered long-form broadcast entertainment, and brought a distinctly Canadian-born sensibility to the heart of American popular culture. His legacy endures not only through thousands of recordings, but through traditions—most notably the sound of Auld Lang Syne at midnight—that continue to echo every year, long after the band has stopped playing.

-Robert Williston

No Comments