Sounds of World War I

Music, Memory, and the Canadian Home Front, 1914–1918

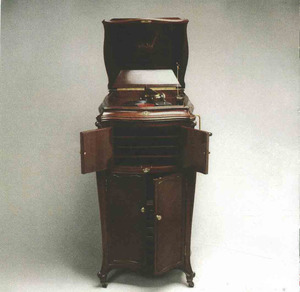

During the First World War, music became an indispensable part of life in Canada—rallying communities, shaping public opinion, and offering comfort amid loss. Whether sung around parlor pianos, performed at recruitment drives, or published as sheet music in downtown Toronto, popular wartime songs helped Canadians make emotional and ideological sense of the Great War.

Unlike in Europe, where soldiers’ trench songs and orchestral laments dominated the musical legacy, Canadian wartime music was shaped largely on the home front. The majority of these songs were published between 1914 and 1918 by small and mid-sized Canadian music houses, such as Whaley, Royce & Co., Thompson Publishing, and Morris Manley, and targeted Anglo-Canadian audiences. These were not concert hall works—they were accessible, catchy, and explicitly designed for mass appeal. Composers such as Geoffrey O’Hara (1882–1967), Daisy May Pratt Erd (1882–1925), and Kenneth McInnis crafted songs that resonated deeply with the public, while others—like Jules Brazil, Alta-Lind Cook, Jean Mulloy, and Frank Madden—emerged as regional figures whose music circulated widely during the war years despite their later obscurity.

🇬🇧 Imperial Loyalty and Recruitment

At the time, Canada’s official flag was the Union Jack, though the Canadian Red Ensign was commonly used as an unofficial national symbol—especially by troops and civilians abroad.

In the early war years, music reinforced Canada’s colonial ties to Britain. Songs like “Good Luck to the Boys of the Allies” (Morris Manley, 1915) and “We’ll Never Let the Old Flag Fall” celebrated enlistment and framed military service as a duty to the King and Empire. Martial rhythms, bugle flourishes, and direct lyrical appeals to “Johnnie Canuck” created rousing calls-to-action. Patriotic music became a staple of recruiting events and fundraising concerts, used to stir public emotion and affirm national resolve.

Notable examples include Hurrah for the Buffs! by Frank Madden, and Do Your Bit (1915), arranged by Jules Brazil. Brazil, active in Toronto throughout the 1910s and 1920s, also arranged Lord Byng (Canada Welcomes You) (1921), while Madden contributed several pieces for Irish-Canadian audiences. One of the most frequently referenced songs of this period was The Maple Leaf Forever, a 19th-century composition by Alexander Muir that regained popularity during WWI. Though not composed for the war, its loyalist lyrics made it a recurring anthem at pro-Empire gatherings.

📚 Robert W. Service: Rhymes of the Red Cross Man

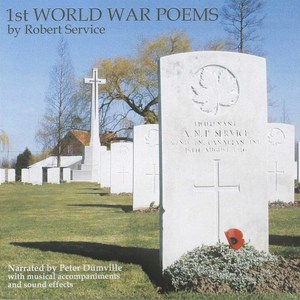

Among Canada’s most enduring literary witnesses to the Great War was Robert W. Service (1874–1958), whose poems captured the grit, sacrifice, and absurdity of modern conflict in rhyming verse. Though already famous for Yukon ballads like The Cremation of Sam McGee, Service served as a Red Cross volunteer and ambulance driver on the Western Front. His 1916 collection Rhymes of a Red Cross Man became one of the war’s most widely read literary works.

With poems such as The Fool, The Coward, and My Mate, Service offered Canadians a raw and relatable glimpse of war through character-driven storytelling and sardonic wit. Other pieces like Only a Boche, Young Fellow My Lad, The Whistle of Sandy McGraw, and When the Piper Plays reflect both the horror and humanity found in wartime trenches. His verses were recited in dugouts, classrooms, and memorial services—becoming part of Canada’s cultural response to the war.

In 2004, a spoken-word CD titled 1st World War Poems by Robert Service was released by Landmark Productions (UK), preserving these works in vivid oral performance. These recordings provide a haunting glimpse into the psyche of trench soldiers, alternating between tenderness and dark humor.

🎭 Satire and Scorn on the Front Lines

Not all wartime music was solemn or reverent. A rich vein of satire and gallows humor ran through the musical and poetic output of the period, especially among those who had served. Robert Service’s Only a Boche pokes caustic fun at the enemy while acknowledging the moral complexity of killing. Similarly, soldier-performers in the trenches often repurposed popular melodies with ironic or subversive lyrics—offering release from the grinding tension of warfare. These satirical expressions became a coping mechanism, and their popularity among troops highlights the darkly comic sensibilities that emerged from life under fire.

🎖️ Gitz Ingraham Rice

Gitz Rice (1891–1947), a Nova Scotian-born songwriter and lieutenant in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, rose to prominence as one of the few Canadian soldiers whose musical contributions directly shaped the war experience. After suffering a gas attack in 1917, he was reassigned from combat and began organizing troop concerts and morale-boosting performances.

His sentimental ballad Dear Old Pal of Mine (1918) became an international hit and was recorded by Irish tenor John McCormack. The song captured the homesick yearning of soldiers overseas and found resonance with audiences across the Allied nations. Other works like Keep Your Head Down, Fritzie Boy were filled with bravado and biting humor, depicting the swagger and sarcasm of the front lines.

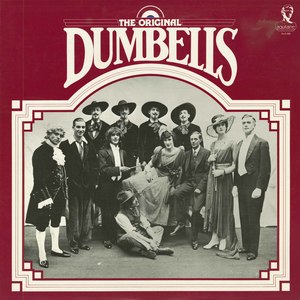

🎭 Morale and Musical Theatre: The Dumbells

In 1917, amid the mire of trench warfare, a uniquely Canadian musical force emerged: The Dumbells, a concert party formed from the 3rd Canadian Division under the leadership of Captain Merton Plunkett. Conceived to raise morale among troops, the group combined satirical skits, sentimental ballads, and spirited ensemble numbers, offering soldiers comic relief and a rare emotional release at the front. Their revue-style shows, performed in makeshift theatres near the trenches, became so popular that they were eventually formalized into The Dumbells Concert Party – The Divisionals.

After the war, the Dumbells became the first Canadian theatrical troupe to tour internationally. They enjoyed a 16-week run at Toronto’s Grand Opera House in 1919, followed by a groundbreaking appearance on Broadway in 1921—an unprecedented feat for a Canadian production. Their touring revue Biff, Bing, Bang featured enduring songs like Gee, Oh Gee! It’s Good to See the Old Home Town Again, Oh! It’s a Lovely War, and My Little Grey Home in the West. These performances bridged wartime experience with postwar nostalgia, reminding Canadian audiences of the resilience and wit forged in battle.

The Dumbells’ recordings and sheet music were widely circulated, and their legacy endured well into the 1930s. They exemplify how music was not only used for propaganda or solemn remembrance, but also for humour, community, and emotional survival. Today, they are recognized as trailblazers in both Canadian music and theatre history.

🌾 Canadian Identity Emerges

By 1916, Canadian patriotism began to shift away from British imagery toward a more autonomous national narrative. This evolution was echoed in songs like I Love You, Canada (Manley & McInnis), which emphasized the vastness and unity of Canada from coast to coast. Sheet music covers began to feature maple leaves, Mounties, and landscapes, subtly replacing the Union Jack with distinctly Canadian symbols. Kenneth McInnis, a co-writer of I Love You, Canada, worked frequently with publisher Morris Manley, contributing to this emerging nationalist sentiment.

At the same time, the Battle of Vimy Ridge (1917) and Canada’s growing international stature contributed to this transformation. Composers and publishers tapped into a public yearning for a uniquely Canadian sense of sacrifice and pride, with songs that spoke not just of loyalty to Britain, but to Canada itself. Lesser-known voices like Jean Mulloy, active in Kingston, Ontario, contributed works such as Johnnie Canuck’s the Boy and Nursing Daddy’s Men, emphasizing the domestic and emotional labor of war in Canadian households.

👩🦰 Gender Roles and Wartime Song

Much of Canadian wartime music addressed—or imposed—roles on women. Songs like I’ll Be Waiting at the Door or Mother, Here’s My Boy cast women as patient supporters and moral anchors of the nation. The typical message: men fought, women waited.

However, not all songs followed this script. The bold 1916 composition Why Can’t a Girl Be a Soldier? by Lindsay Perrin questioned the exclusion of women from combat, asking why they couldn't "carry a gun good as any mother’s son." Perrin’s piece remains one of the few Canadian wartime songs to explicitly challenge gender norms, prefiguring the postwar evolution of women's roles. Similarly, Daisy May Pratt Erd, a Canadian-born composer who served as a Yeomanette in the U.S. Navy, wrote extensively about women’s contributions to the war effort and later advocated for female veterans’ recognition.

🎶 Everyday Life and Emotional Relief

Many wartime songs were less political and more personal. Love ballads, farewell songs, and longing laments—such as Keep the Home Fires Burning and Till the Boys Come Home—were widely sung in drawing rooms and at public events. These tunes offered comfort in the face of separation, and gave voice to the private emotional toll of the war.

Geoffrey O’Hara, one of Canada’s most prolific composers, contributed more than 500 songs during his career, including the iconic K-K-K-Katy (1918), written for a stuttering soldier in love. O’Hara also trained soldiers in patriotic singing and worked to promote morale through music across Canada and the U.S. Community concerts, vaudeville stages, Red Cross drives, and school assemblies all featured live performances of wartime songs, helping to bind communities together in grief, hope, and collective effort.

🪖 Ernest MacMillan and Ruhleben

One of the most remarkable stories of Canadian resilience through music comes from composer Ernest MacMillan. While attending the Bayreuth Festival in Germany in 1914, he was arrested as an enemy alien and interned at the Ruhleben civilian camp near Berlin. Over four years in captivity, MacMillan organized lectures on Beethoven, participated in chamber music ensembles, and conducted performances with other imprisoned musicians. His efforts turned the camp into an unlikely hub of musical activity and cemented his role as a cultural leader—foreshadowing his future influence as a conductor, educator, and nation-builder in postwar Canada.

🗂️ Legacy and Rediscovery

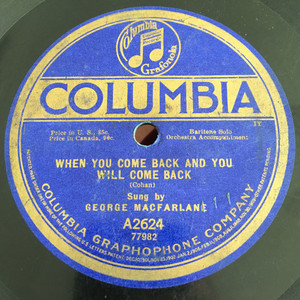

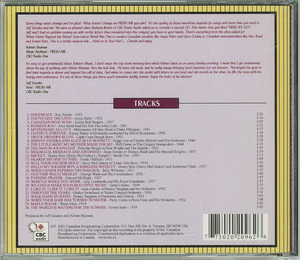

Though many of these songs faded from public memory after the war, their influence endured. The symbolic imagery, gendered language, and imperial loyalty expressed in these works would help shape Canadian music and identity into the interwar years. Today, efforts by historians and archivists—including the digitization of 78 RPM records and sheet music at institutions like Library and Archives Canada, WartimeCanada.ca, the Canadian Museum of History, and The Museum of Canadian Music—have made this music available once again.

Notably, In Flanders Fields by John McCrae was set to music by several composers during and after the war, including G. Geoffrey Booth and W. H. Hewlett. These musical versions helped popularize the poem globally and reinforced its power as a symbol of remembrance.

🎖️ War Songs Related to Canada 🌍 World War I

Songs:

Canada, I Hear You Calling (Harold N. Tennent)

The Canadian Guns (F. E. Parkes)

Do Your Bit (Jules Brazil)

Dear Old Pal of Mine (Gitz Rice)

For the Glory of the Grand Old Flag

Freedom for All Forever

Good Luck to the Boys of the Allies (Morris Manley)

Hats Off to the Flag and the King

Here’s to Tommy

Highlanders! Fix Bayonets!

The Homes They Leave Behind

Hurrah for the Buffs! (Frank Madden)

I Love You, Canada (Kenneth McInnis & Morris Manley)

In Flanders Fields (John McCrae / music by G. Geoffrey Booth or W. H. Hewlett)

Joan of Arc, They Are Calling You (Charles Dumont / Alfred Bryan)

Johnnie Canuck’s the Boy (Jean Mulloy)

Keep Your Head Down, Fritzie Boy (Gitz Rice / Sam M. Lewis / Harry Ruby)

La Brabançonne (François Van Campenhout)

Land of the Maple

Laurentian Echo

The Made in Canada Campaign Song

Maple Leaf Forever (Alexander Muir)

The Old Destroyer Squadron

Our Hearts Go Out to You, Canada

Strike for the Grand Old Flag

Take Me Back to Canada

Take Me Back to the Land of Promise

They Sang God Save the King

Three Cheers for the Army and Navy

Tommy Atkins (S. R. Henry / Frederick Weatherly)

Valcartier

We’re from Canada

We’ll Never Let the Old Flag Fall

Why Can’t a Girl Be a Soldier? (Lindsay Perrin)

Boys from Canada (Alta-Lind Cook)

K-K-K-Katy (Geoffrey O’Hara)

Nursing Daddy’s Men (Jean Mulloy)

Lord Byng (Canada Welcomes You) (arr. Jules Brazil)

The Irish Laddies to the War Have Gone (Frank Madden)

Marches:

Canadian Patrol

Dominion of Canada March

Hands Across the Sea (John Philip Sousa)

In Old Quebec

Jack O’ York

Les Alliés

Vive La Canadienne! (Traditional)

— Robert Williston, Museum of Canadian Music

No Comments