Information/Write-up

Singer Eric Mercury began performing when he was hardly old enough to attend public school. His family worked together as a musical group, appearing at local functions at churches, schools, and such. After he got older, Mercury moved on from his family band to a few rock and R&B groups that let him try some new styles, and come into his own rhythm. In the late '60s, he began performing solo, recording a debut album in 1969. A few more full-length offerings followed during the '70s, before he moved on to work as a producer, songwriter, and to appear in at least one musical.

Eric Mercury was born and raised in Toronto, Canada. He entered this world as a member of a skilled musical family. That gave him the chance to polish natural talents of singing and performing at an age when most children are happy simply mastering the alphabet and double-digit numbers. Just before the '60s rolled in, Mercury went out on his own, joining groups like the Pharaohs before moving up from member to frontman with Eric Mercury and the Soul Searchers.

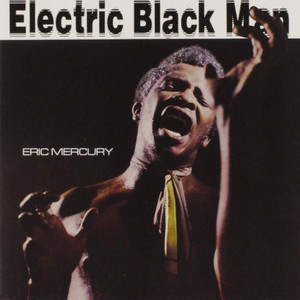

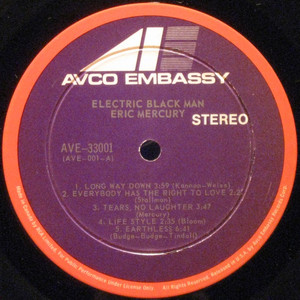

In 1968, Mercury made two substantial changes in his life. First, he left Toronto behind for Chicago in the United States. Second, he left the safety of a group and went solo. A short year later he was working under the Avco Embassy label, and witnessed the release of his solo debut album, Electric Black Man. During the next decade he recorded three more albums, Funky Sound Nurtured in the Fertile Soil of Memphis, Love Is Taking Over, and a self-titled offering. The latter was released in 1975, and was the last solo recording he made.

In the '80s Mercury began working more behind the scenes in the music world, both in Canada and the United States. Besides working as a producer, he also wrote both songs and jingles. "It's Time for Me to Love," "Listen With Your Eyes," "You Bring Me to My Knees," "Long Way Down," and "Everybody's Got the Right to Love," are just a few of the funky-meets-blues type tunes fans can enjoy from Eric Mercury's albums.

-Charlotte Dillon, AllMusic

Charismatic singer Eric Mercury turned heads with Electric Black Man album

Eric Mercury was an insistent soul-rock and R&B singer from Toronto who had significant ups and occasional downs over a long, productive career in the music business.

“It’s a long way down from up,” Eric Mercury sang on the first song of his debut album Electric Black Man from 1969. The line was verifiable – the singer-songwriter had done the calculations firsthand.

Mr. Mercury, an insistent soul-rock and R&B singer from Toronto who had significant ups and occasional downs over a long, productive career in the music business, died on March 14 in Montreal after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 77.

In the summer of 1968, Mr. Mercury was fronting one of Canada’s more popular R&B bands, the Soul Searchers. The group was working in Halifax when the charismatic showman with leading-man looks decided to strike out on his own. Devastated by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., inspired by the musical vibrancy of American folk singer Richie Havens and taken with revolutionary Black Power notions, Mr. Mercury ventured to New York with nothing but a library card in his back pocket and $52 to his name.

While attempting to score gigs and make connections, the homeless Mr. Mercury found shelter at the Port Authority Bus Terminal and slept in an abandoned Studebaker. Walking by the Cafe Au Go Go night club in Greenwich Village one evening, Mr. Mercury noticed that Blood, Sweat & Tears was playing. He was standing in the doorway when the band’s singer, David Clayton-Thomas, spotted him.

“This guy is my favourite singer in the world,” Mr. Clayton-Thomas told the audience, pointing out Mr. Mercury.

The pair knew each other from Toronto. “Eric was my old friend from Yonge Street,” the Grammy-winning Spinning Wheel singer told The Globe and Mail. “We used to sing duets at the Zanzibar Tavern.”

At Cafe Au Go Go, Mr. Clayton-Thomas and Mr. Mercury reacquainted on the fly, taking part in an improvised jam. The unexpected showcase exposed Mr. Mercury to a few talent scouts on hand and led to his break into the music business in New York. “My life changed from that moment,” he later told Canadian music journalist Bill King.

After signing a deal with well-established record-making team of Luigi Creatore and Hugo Peretti, Mr. Mercury recorded Electric Black Man, a brash, declarative exercise in psychedelic soul released on the AVCO Embassy label in late 1969.

From there, Mr. Mercury went on to make two studio albums for Enterprise Records, an imprint of prestigious Stax Records. The first of which was 1971′s Funky Sounds Nurtured in the Fertile Soil of Memphis That Smell of Rock, perhaps the most floridly descriptive album title in the history of recorded music.

Mr. Mercury’s singing style was comparable to the raw-voiced ardour of Wilson Pickett, with no small dose of the blue-eyed-soul urgency of a Paul Rodgers. His career (which began as a church music singer at the age most children were still learning to tie their shoes) spanned doo-wop vocalizing as a teenager in Toronto in the late 1950s to his final single Bright Eyed Woman in 2019.

In between, the irrepressible and affable Mr. Mercury starred in a stage production of Jesus Christ Superstar, performed a pair of songs at the legendary Wattstax benefit concert at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in 1972, appeared in the films American Hot Wax and The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh, and co-produced the 1980 album Roberta Flack Featuring Donny Hathaway.

For that album, Mr. Mercury and Stevie Wonder co-wrote You Are My Heaven, a duet by Ms. Flack and Mr. Hathaway. It was the last song Mr. Hathaway ever recorded. The great but troubled soul singer was found dead on the pavement below the window of his 15th-floor room in New York’s Essex Hotel on Jan. 13, 1979.

Though a review of Electric Black Man in the Toronto Star predicted that Mr. Mercury “should become a major rock figure,” the projected fame didn’t happen. At the Memphis-based Stax Records, where Mr. Mercury worked with big-name producers Steve Cropper and Al Bell, his career did not accelerate.

“Eric told me he felt like a fish out of water at Stax,” said Rob Bowman, a friend of Mr. Mercury and an ethnomusicologist who wrote the 2003 book, Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. “He was a Canadian who nobody in the American R&B world knew, and the people at Stax didn’t know what to do with him.”

Race may have been an impediment, particularly in the singer’s home country. “Being in Canada, whatever colour you were was rough,” Mr. Mercury said in an interview in 2006, referring to his decision to try his luck in the United States. “But being Black was rougher.”

In addition to his skin colour, Mr. Mercury’s smarts might have worked against him. “Being a male Black artist in the music industry has always had its drawbacks, particularly if you were intelligent, which Eric was,” said T.S. Monk, a collaborator with Mr. Mercury and the son of jazz icon Thelonious Monk. “Eric knew the business, and when you know the business, you ask questions. We talked about this often – the industry doesn’t like smart artists.”

Whatever the reason, Mr. Mercury never achieved the status many felt he was destined to achieve. “Unless you truly wanted to know about Eric,” Mr. Bowman said, “you wouldn’t be aware of his story.”

Eric Alexander Mercury was born in Toronto on June 28, 1944. He was the final child of seven born to Methodist minister George Luther Mercury and deaconess Gladys Viola Mercury (née Smith). His father was from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines; his mother hailed from Jamaica. They were community leaders working out of the British Methodist Episcopal Church, just west of Toronto’s downtown core.

At a young age Mr. Mercury was a soloist in the junior choir, directed by his aunt. By 12 he was playing and touring with a marching-and-manoeuvring trumpet ensemble.

Inspired by the American group Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, as a teenager himself Mr. Mercury joined the vocal group the Pharaohs with fellow doo-wop enthusiasts including Jay Jackson. (With his sister Shawne Jackson, Mr. Jackson would go on to front the Majestics, a 13-piece R&B band that was part of the “Toronto Sound” of the late 1960s.)

After the Pharaohs, Mr. Mercury formed the Soul Searchers with singer Diane Brooks, William (Smitty) Smith on the Hammond B3 organ and others. The jazzy R&B ensemble graduated from teen clubs to licensed bars in Toronto before playing a show at The Scene club in New York, where Tiny Tim was the emcee for a bill headlined by the Doors and the Chambers Brothers. “I was confident that I was as good or better than anyone else singing in the show,” Mr. Mercury recalled in 2019.

It was after Ms. Brooks left the Soul Searchers that Mr. Mercury left Canada and returned to New York as a solo artist. After his impromptu, attention-getting appearance with Mr. Clayton-Thomas at Cafe Au Go Go, Mr. Mercury went back to the venue with a band that included a four-piece horn section and guitarists Rick Derringer and Elliott Randall (a session player who later contributed the solo to the Steely Dan song Reelin’ in the Years).

Approached by Mr. Creatore and Mr. Peretti, Mr. Mercury was asked for his terms. The starving musician asked for US$25,000 and a Green Card. They gave him $12,500 and arranged for his permanent resident status. Done deal.

Electric Black Man was recorded by prominent engineer Tony Bongiovi and produced by Gary Katz, who would go on to produce a string of seven Steely Dan albums.

Providing background vocals on the album were Valerie Simpson (one half of Ashford & Simpson, the distinguished husband-and-wife songwriting-production team and recording duo with Nickolas Ashford) and Cissy Houston.

“Cissy couldn’t find a babysitter, so I told her to bring [her daughter] with her,” Mr. Mercury later told Jake Feinberg, host of music podcast The Jake Feinberg Show. The child was Whitney Houston.

The tracks for Electric Black Man were laid down at New York’s Record Plant studio at the same time Jimi Hendrix was there recording material that would be released after the guitarist’s death in 1970.

“We worked from noon to midnight,” Mr. Katz told The Globe. “When we left, Jimi would be sitting on a plastic chair right outside the door, with a coterie of kids and other people. We’d open the door and he would walk in. The room was full of Marshall amplifiers, from floor to ceiling. We’d sit outside the door and listen to Jimi play.”

Upon its release, Electric Black Man made noise of its own. Mr. Mercury and his band played coast to coast, from the Fillmore East in New York to the Fillmore West in San Francisco.

Pop-culture aficionados will remember Mr. Mercury as lead singer in Gatorade’s “Be Like Mike” advertising campaign starring basketball superstar Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls. Mr. Mercury lived in Chicago and Los Angeles before eventually returning to Canada.

Though Mr. Mercury had a personal (as well as a professional) relationship with the superstar American singer Ms. Flack, he tended not to talk about the romance publicly.

“I don’t think Eric had any trouble in getting women to fall in love with him,” Mr. Bowman said.

To those who knew Mr. Mercury well, he was known as “Merc,” an enthusiastic listener, a spiritual seeker, an inquisitive learner, a socially aware thinker and a dedicated conversationalist.

In 2006, the musician was interviewed for a planned Canadian documentary on his life and career. A producer on the project remembered that the director of photography was concerned Mr. Mercury was performing for the camera, with a lot a bravado and showiness.

“But I told the director of photography that I thought that was just Eric,” Daniela Saioni told The Globe. “He was a showman, right? It was natural for him, and not a put-on. I got the sense that Eric didn’t turn off.”

The film, which was to include a proposed concert by such luminaries as Ms. Flack and Mr. Clayton-Thomas, never got off the ground owing to a lack of financing. “I think the project was a little ahead of its time,” Ms. Saioni said. “I think Canada is only now finally investing in its Black stories.”

The existing footage includes Mr. Mercury being asked to define success. “It’s the depth of the journey,” he said, mentioning his membership in the lineage of the musicians he admired. “I’m a soldier, he continued, “a successful soldier.”

Mr. Mercury leaves his son, Blake Mercury; 19 nieces and nephews; his close friend Martine Levy and many other friends.

-Brad Wheeler, Globe and Mail, Mar 23, 2022

No Comments