Information/Write-up

This story originally appeared in the January 21, 1993 issue of Rolling Stone.

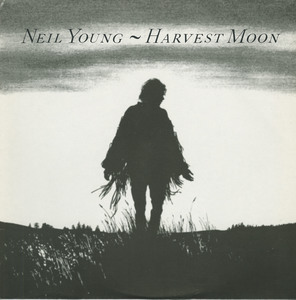

Neil Young proves life in rock & roll can begin again at fortysomething.

“Did you see Dracula?”

Neil Young breaks into a wide grin over a bowl of postconcert fruit salad. “Man, they got some wind in Dracula that’s scary,” he says. “It’s beautiful.”

Later that night, on his vintage 1970 tour bus parked outside a Chicago hotel, a discussion about growing up in Canada quickly leads back, somehow, to thoughts of Transylvania. “I can’t get it out of my mind!” Young exclaims, shaking his shaggy head. “I got to go back and see it again.”

Though his hair and the massive mutton chops might seem to indicate more of an affinity for the Wolf Man, Neil Young and Count Dracula actually have a surprising amount in common. Both spend much of their time underground, occasionally surfacing with surprising, even shocking results. Both can change style and persona to get their work done. And – most significantly – both seem not to grow older as the years go by.

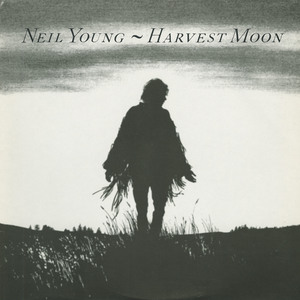

But Harvest Moon is more complicated than a simple nostalgia trip or a remake. Beneath the pedal steels and dulcet tones of Harvest, the twenty-six-year-old Young sounded wizened beyond his years as he first confronted aging and mortality. “As the days fly past, will we lose our grasp?” he asked in his eerie, pinched voice on the title track; on “Are You Ready for the Country?” he sang, “I ran into the hangman, and he said, ‘It’s time to die.’ ” Even “Heart of Gold,” Young’s only Number One single, ended each verse with the tag “and I’m getting old.”

Harvest Moon, on the other hand, is a chronicle of survival, focusing on loss and compromise and the ultimate triumphs of being a married father approaching fifty. It’s full of bittersweet tributes to lost friends, dead hounds and love grown old. “What this album is about is this feeling, this ability to survive and continue and grow and get higher than you were before,” says Young. “Not just maintain, not just feel well. Not just ‘I’m still alive at forty-five.’ You can be more alive.”

It hasn’t been an easy ride these two decades for Young. He has suffered through the deaths of several musicians close to him, from Danny Whitten (guitarist in Crazy Horse, Young’s frequent garage-rock collaborator) in 1972 to the passing in 1991 of Steve Lawrence, saxophonist in his bluesy big-band project the Bluenotes. Young went through a controversial, contentious period artistically throughout the 1980s, ending up in a surreal court battle with Geffen Records, his label at the time, for making what the company called “unrepresentative” albums – for making albums that didn’t sound like Neil Young albums, whatever that could possibly mean. Most harrowing, he has two sons, by two different women, both of whom were born with cerebral palsy (he also has an eight-year-old daughter who does not have the condition).

Yet Young has managed to produce the most consistently compelling body of work of any musician of his generation. Who else has remained so relevant, so vital, so influential in so many musical genres? The last few years in particular – beginning with Freedom, in 1989, through the cataclysmic Ragged Glory (1990) and his subsequent tour with Crazy Horse, and continuing with his soaring, show-stealing performance at the Bob Dylan tribute last October and the release of Harvest Moon – have seen Young at an artistic peak, following his own muse as always and resolutely refusing to fall into the “oldies act” category that has beset virtually all of his contemporaries.

“If you’re charged up and have all this experience, what else is there?” Young says of his amazingly graceful rock rock & roll maturation. “When you’re young, you don’t have any experience – you’re charged up, but you’re out of control. And if you’re old and you’re not charged up, then all you have is memories. But if you’re charged and stimulated by what’s going on around you and you also have experience, you know what to appreciate and what to pass by. And then you’re really cruising.”

The head of corporate marketing for WTTW-TV, Chicago’s PBS affiliate, strides to the front of the room in the station’s studios. Neil Young is about to tape the first installment of Center Stage, a new series coproduced by WTTW and VH-1. The station rep welcomes the small crowd, filled with industry weasels and local music-biz types, and makes one request of the 200 or so invited guests.

“Anybody who’s got a tie on or is looking too corporate,” he says, “could you please take them off? It’s important that this look like a Neil Young crowd.”

The next night, though, at an actual Neil Young concert in front of actual Neil Young fans, there are quite a few ties in the house. Their owners are seated next to kids in frayed flannel shirts, next to preppie types in Docksiders, next to rockers in leather jackets. Garth Brooks listeners mingle with Nirvana-heads. Woodstock meets Lollapalooza. An aging hipster in a linen jacket shares a joint in the men’s room with a fresh-scrubbed teen.

“Can we get it together, can we still stand side by side?” Young sings in Harvest Moon‘s “From Hank to Hendrix.” With the continuing fragmentation of the pop-music audience, a Neil Young solo concert is as close to a rock & roll consensus as you’re going to find.

“They come from everywhere for the acoustic thing,” Young says. “They won’t meet anywhere else. But once I define it with a band, I lose half of them and bring in a bunch more extremists from one place or another.”

The acoustic thing. Young has been touring off and on for the past year with just a fleet of guitars, a couple of pianos and a banjo or two, hitting two or three cities at a time and then retreating – vampirelike – to his ranch in California for a few weeks. The one consistent element in these shows is his refusal to use a set list at any time – much to the chagrin of the Center Stage film crew, which scrambles to shoot Young as he wanders from instrument to instrument, scratching his head and figuring out what he wants to play next.

“There’s a lot I get out of doing this acoustic thing that I don’t get any other way,” Young says. “It opens up the music and the songs and what they’re about. Being able to pick things out and change them around. A band can cover that stuff up. There’s nothing worse than walking out and knowing exactly what you’re going to do. At this time of my life, I don’t need that.”

The flip side of that, of course, is not knowing what the audience is going to make of any given Neil Young show. The Center Stage taping is spectacular, with Young compensating for his concerns about the bright lights of TV by delving even deeper into the songs. He ends up playing twenty songs, almost two hours, for a show that will run only a half-hour (an hour-long version will appear on PBS next summer). A painfully intense rendition of 1977’s “Like a Hurricane” on the pipe organ is the highlight – Young would later refer to it as “the Transylvania version,” though it actually felt closer to Phantom of the Opera. (Too lunatic for VH-1, apparently: The song didn’t make the cut for the show.)

The following night’s concert at the gorgeously restored, turn-of-the-century Chicago Theater, however, is not such a pretty sight. The crowd is boisterous and vocal from the opening minutes. Several times, Young starts to play a song only to cut it short, claiming that he can’t hear himself. “Don’t think I’m fucking with you, okay?” he pleads from the stage. “But some of you guys who drink a lot of beer, you know how loud you can be compared to this.”

Finally, Young delivers a brief, good-natured greatest-hits set, cutting off after about seventy-five minutes. “Tonight was the opposite of what I like to do on a musical level – tonight was survival,” he says after the show. “But you have to be able to read it and roll with it. I don’t have to play a sensitive song while people are yelling. I play the songs for myself, and if I’m distracted by the audience, I’ll just stop.”

Young bears no malice for this segment of his following, the beer-swilling guys in Allman Brothers T-shirts who turned last winter’s performances at New York’s Beacon Theater into a nasty, heated battle between his desire to play unreleased new songs and their calls for his familiar rock & roll raveups. “Don’t you have a lot of friends like that?” he asks. “Big outgoing guys who have a few drinks and just get blown out, but if they aren’t drinking, their soulful side comes out and they’re actually real sensitive? They just get so high, they feel it so much, that they think they’re alone in their van listening to the songs.”

Harvest Moon might seem like the ultimate concession to Young’s old fans, but he sees it as a valid, even experimental enterprise. “People had been asking me to do it for twenty years, and I never could figure out what it was in the first place,” he says. But when he wrote a batch of new songs and finished some old ones last summer in Colorado, the Harvest sound was what he heard in his head. “That’s when I discovered what the hell I was doing, but only because the songs made me do it,” he says. “It just happened again, whatever it was that happened back then.”

The track “You and Me,” a quiet paean to domesticity that quotes from the Harvest hit “Old Man,” is the musical link between the albums, according to Young: “That song was started in 1975, but I never finished it. In 1976, [bassist] Tim Drummond heard it and said: ‘You’ve got to finish that, man. That’s like Harvest stuff, let’s do that.’ And that kinda freaked me out, I got spooked by it, because it was like someone said what it was before we did it. I don’t want to feel like I’m just filling in the numbers.” But along with this new batch of compositions came a new intro and last verse, and the twenty-year-long jump was completed.

In the notes to his 1978 anthology Decade, Young wrote: ” ‘Heart of Gold’ put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch.” He still expresses ambivalence about Harvest: “When people start asking you to do the same thing over and over again, that’s when you know you’re way too close to something that you don’t want to be near. I can’t hold that against [Harvest], which I did; it’s certainly got the depth of the other records. But it took a while to get to that. I just didn’t want to do the obvious thing, because it didn’t feel right.”

Obviousness or predictability would be the last things of which Neil Young could be accused. Young asserts that all the disparate styles he has explored – from his Sixties work with folk-rock pioneer Buffalo Springfield to the altered electro-vocals of Trans (1982) to the rockabilly of Everybody’s Rockin’ (1983) – are related, that the relevance his listeners find in the more accessible records is of a piece with the weirder, sometimes patently incomprehensible stuff. “Deep inside [the Rockin’ band] the Shocking Pinks or Trans is the same stuff that people are hearing now,” he says. “It’s just buried; it’s not on the surface. And some of it is more intense than what people are hearing now.”

Nor has Young ever turned his back on any part of his musical past. His tour bus, after all, still has Buffalo Springfield emblazoned on the back (making it hard to miss parked outside the stage door after a show). He doesn’t even rule out another go-round with his cohorts Crosby, Stills and Nash. “I’m good friends with all of them, and we could literally be making music together anytime,” Young says. “If we had the songs and the circumstances were right, we could do something great. I think the potential’s still there.”

Driven, open, restless (he even named the band he took to Europe after Freedom Young and the Restless), Young’s primitive guitar screech and yowling voice have served as lasting inspiration for wandering souls and fuck-ups of several generations now. In the 1990s, Neil Young is simply so anachronistic that he’s cutting edge.

“I like to walk,” he says when asked what he does during a typical day on tour after a lifetime in the rock & roll business. “A lot of times, I’ll stop the bus and walk for three or four miles and then let the bus catch up with me on the road.”

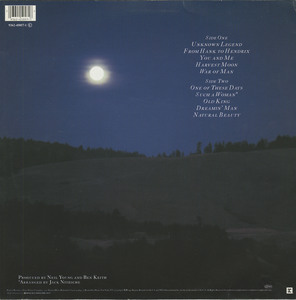

Neil Young doesn’t listen to records. “I’m more interested in what the music of the times is,” he explains over juice and coffee in the café of his Chicago hotel, still wearing the same Chicago Blackhawks T-shirt he put on after the preceding night’s show. “If it’s on the radio or somebody else is playing a tape, that’s how I hear music. It’s what I hear in the environment.” He must travel in a wide-open environment indeed, for he casually drops references to artists ranging from Trisha Yearwood to Pearl Jam, from R.E.M. to Patty Smyth. He flashes a goofy grin on the Harvest Moon inner sleeve bedecked in a Fishbone T-shirt.

Young discusses music – any music – with unabashed love; it’s incredible to hear anyone talk about bands without a shred of attitude or exclusion. As one who helped popularize country rock in the Seventies, for instance, he maintains that today’s country boom is the result of listeners losing interest in singer-songwriters like himself.

“I drove a lot of people away by singing so loud and abrasive and the feedback and all, and I’m not the only one who’s done that to them,” Young says. “A lot of people turned to country because it’s more like Seventies rock & roll. Pop and rock have just changed their name to country. Garth Brooks – he’s a pop star, like what’s his name, Bryan Adams. But he sings about things that are more rural, more country values. People like to hear about things they can relate to, not just some posey kind of antilifestyle attitude or whatever.”

As for rap, the bane of many of his peers’ musical existence, Young practically jumps out of his chair with enthusiasm. “I love rap!” he declares with a sparkle in those familiar, piercing eyes, professing a particular fondness for Ice-T. “It’s speaking to the people on the streets. It’s a whole new way of communicating that’s so open to saying exactly what the hell’s on people’s minds in a clever way, a way that you can listen to and move your body to. Similar to, like, ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’ Dylan is early rap. What the hell’s the difference?” To those who resist rap’s charms, he adds, “This is the shit that’s going to keep music alive – don’t close it off because you don’t understand it.”

The new music with the clearest links to Young’s work is grungy guitar rock. His turbulent instrumental squalls and Crazy Horse’s thunderous backing – not to mention his flannel-centric wardrobe – echo through the work of Seattle’s rising stars and a range of alternative artists from Dinosaur Jr. to the Jayhawks to Matthew Sweet. Many of today’s postpunk college guitar bands claim him as a spiritual godfather; some of them – including Soul Asylum and the Pixies – covered Young songs on The Bridge, a 1989 tribute album.

Young is loath, however, to take credit as an influence on anyone. “It’s not me, it’s just the music,” he says wearily. “I play it, and they play it. Link Wray was doing it a long time ago. Then Hendrix, now we’ve got all the grungers and the distortion thing. It’s just going farther and farther, which it should. It’s being developed.”

Not since Young put Johnny Rotten and Elvis in the same song on Rust Never Sleeps in 1979, however, did he embrace the next wave as he did when he took Sonic Youth on the road with Crazy Horse in 1991. “They’ve got this thing happening that I enjoy,” he says of the art-punk superheroes. “It’s soothing to me; it was very soothing before I went onstage to hear that feedback through the cement walls.”

The summit of noisy icons from two generations took its toll on Young, however. Playing in the center of a jacked-up guitar blitzkrieg for six months damaged his ears. “I had hyperacoustis,” he says. “I heard everything very loudly. Now it’s back to normal, but I still don’t like going into loud places. I had to rest for a long time and get everything together.

“Those shows were really fucking loud,” Young continues. “Loud in the way a crashing plane is loud, amped up for that war sound, that kind of thing. That’s what we were going for.”

The entire tour was shot through with the spirit of war, which started while Young and Crazy Horse were in rehearsals. Most overtly, Young put a huge microphone stand tied with a yellow ribbon at center stage and added a blistering version of “Blowin’ in the Wind” to the set. “That war really left a mark on me,” he whispers back in the bus. “We were playing so raucously, so violently, really like a bombardment. It was like we were there. It was very military sounding at times – big machinery, unbelievable power and destruction. That was our sound.”

Young’s bitterness over the gulf war, which lies behind a track on Harvest Moon titled “War of Man,” has given way to excitement, tinged with skepticism, about Washington’s new administration. “It has its comedic side,” he says of the Clinton regime, “but it’s cool that you go to places and a lot of working people are happy. They think that if things don’t change right away, at least they’ve got somebody who knows who they are.

“But,” Young adds, “I always try to get behind the guy steering the ship. That’s the kind of guy I am.”

It was a similar attitude that resulted in Young’s most notorious political statements when he spoke out in support of Ronald Reagan in the early Eighties. Despite his ultimate dissatisfaction with the past twelve years of Republican rule, though, he has no wish to recant those opinions.

“I feel exactly the same as I did when that was going down,” Young says, narrowing his formidable eyebrows. “There were some things Reagan liked that I liked. The main component of it was that people have got to talk to each other and help themselves and that government can’t completely take care of them by making a bunch of promises and programs. It can’t be done that way to the exclusion of working together on things like child care. That was his point – get together, people. Organize your communities.

“I agreed with that,” Young says. “But because I agreed with that one thing and similar types of points, then I was a Reagan backer. It was a shock for some people that I could agree with anything that that man would say. But I’m not into this judgmental, religious-right kind of thing. My ideals don’t run along those lines.”

Onstage he may resemble an affable gas-station attendant or a psychopathic lumberjack, while in conversation he looks more like your burned-out ex-hippie uncle. Somewhere along the way, though, Neil Young has become the very model of all that “family values” should really mean. “My family is a unit that’s behind my music and doesn’t inhibit it,” he says. “The most beautiful thing about my wife, Pegi, is that she never gets in the way of my music. She doesn’t have an attitude about certain kinds of music. For her to have an attitude about this or that, then if I go into that kind of music, I’m thinking, ‘Right here in the house we have someone who doesn’t like this at all.’ I never have that with her; there’s no restrictions that way.”

His marriage, his life on the ranch with his kids and the cars and antique train sets he collects serve as the truest metaphor for Young’s work. “The real music of my life is my family,” he says. “I didn’t keep this marriage together just by doing the same thing over again that I was doing when I got married. I didn’t get pigeonholed into having only one personality, like a lot of people do. They kind of become someone that they’re not. And in music, if you do that, you’ve had it.”

On “Unknown Legend,” Harvest Moon‘s opening track, Young sings, “You know it ain’t easy/You got to hold on,” and the rewards of persevering through difficult, even tragic times are evident when he speaks of his home life. He spent much of the Eighties struggling to come to terms with his sons’ disabilities, and he has said that his anger and frustration and his family’s experience with various rehabilitation programs inspired the impenetrable, tortured work of that era. These days, though, his craggy face looks as thoughtful and peaceful as his voice sounds on the new album. After helping to found the Bridge School, outside of San Francisco, for physically challenged kids like his sons, he now stages an all-star benefit each year to raise funds. It is his involvement with his children that now seems to keep Young happier and fresher than anything else.

“Every year now for my birthday party we do the same thing,” Young says, beaming. “I build a fire, set up all the logs and build it myself. Then after dark, Pegi comes out and lights it. Then the kids come home from school, and we have all their little-kid friends and their parents over. The people that come to my party are chosen because they’re the parents of my children’s friends. They all come down to the fire, and we roast hamburgers and hot dogs and stuff and sit around the fire. After we have dinner, they come down with marshmallows and they all roast marshmallows. So every year at my party, the kids all come. They can’t wait. It’s like a big day for them. I don’t know what that means, but that’s us.”

The solo acoustic shows that started when he wrote the songs for Harvest Moon are all over, at least for now, or so Young says. “Harvest Moon is almost a year old now,” he says. “I’m almost finished doing this.” Of course, in 1988 he said he probably wouldn’t work with Crazy Horse again, calling their sound “a younger kind of music,” only to record the majestic Ragged Glory with them the next year; “Yeah, well, that’s typical,” he says of that particular change of plans. Meanwhile, he continues to work on a long-anticipated multivolume retrospective of his career (the plans now call for different configurations “depending on how deep you want to get into it”) and an autobiography.

Most immediately, though, Young is starting to hear the next sound in his head. He doesn’t know what it is yet. He sure had fun playing the electric guitar again at the Dylan tribute, but maybe there’s another band, new or old, to work with. The only sure thing is that it’s time to move on.

Alan Light, rollingstone

No Comments