Information/Write-up

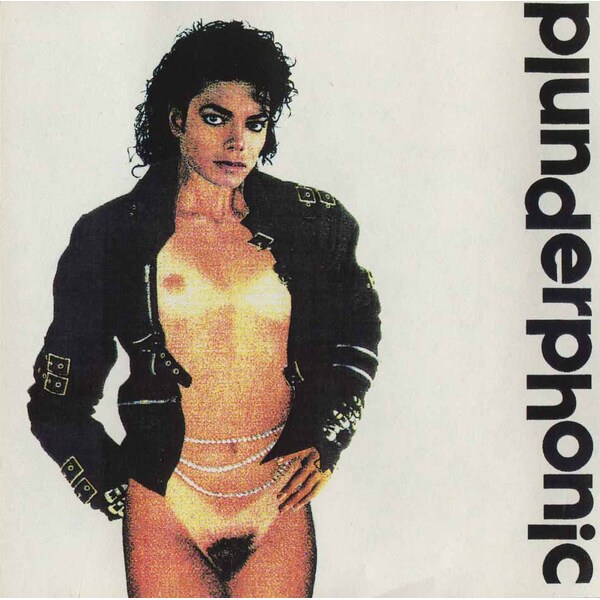

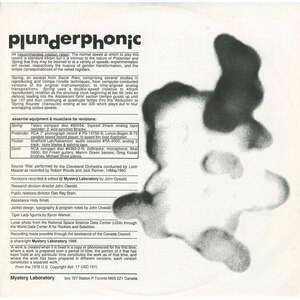

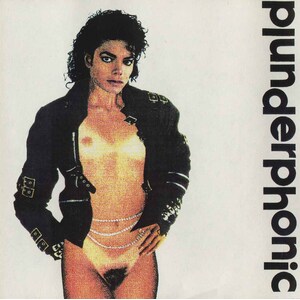

Here is the revolutionary sampling EP by John Oswald entitled "Plunderphonics", released in 1988. The EP of 'audio piracy' was the first of it's kind and was released privately on Mystery Laboratory / World Record Corp. WRC1-5744.

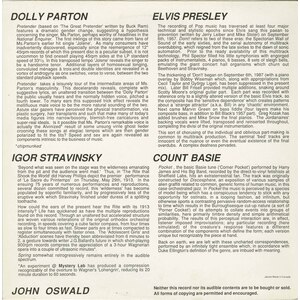

'Spring' was recorded on Telarc compact disc #80054; 3speed 2track analog tape recorded; 2 wild-synched 8tracks;

'Pretender' was recorded on RCA 7" phonograph record #PB-13756-B; Lenco-Bogen B-75 variable speed record player; hi-speed bin loop duplicator;

'Pocket' was recorded on Sheffield Lab/Nakamichi audio casette #RA-4000; analog 2track; razor blades & splicing tape;

'Dont!' was recorded on RCA compact disc #6382-2-R; 2x8tracks; microphone; Akai S900; Bill Frisell guitars; Marvin Green basses; Greg Kozak brushes; Michael Snow pianos.

Jacket design was by John Oswald. Tiger lady figurita by Byron Werner. Lunar photo from the National Space Science Data Center (US) through the World Data Center A for Rockets and Satellites. Recording was made possible through the assistance of the Canada Council.

John Oswald, from Kitchener, Ontario, has released approximately 20 different titles, starting with 'Improvised' in 1978 with Henry Kaiser on Music Gallery Editions MGE 12.

John wrote a paper in 1985 entitled "Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative" http://www.plunderphonics.com/xhtml/xplunder.html

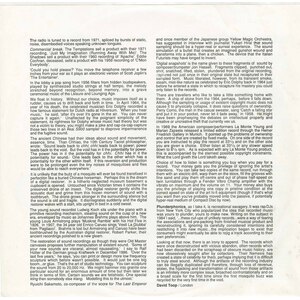

liner notes:

David Toop on Plunderphonics The radio is tuned to a record from 1971, spliced by bursts of static, noise, disembodied voices speaking unknown tongues. Commercial break. The Temptations sell a product with their 1971 recording, 'Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)'. The Shadows sell a product with their 1960 recording of 'Apache'. Eddie Cochran, deceased, sells a product with his 1959 recording of 'C'Mon Everybody'. 'Could you hold please?' You move the telephone receiver a few inches from your ear as it plays an electronic version of Scott Joplin's 'The Entertainer'. In the lobby a pop song from 1956 filters from hidden loudspeakers, played by synthesized studio strings at half tempo, the melody stretched beyond recognition, beyond memory, into a grave ceremonial music of the Leisure and Lounging Age.We float in history. Without our choice, music imposes itself as a rudder, causes us to drift back and forth in time. In April 1964, the year of his death, the celebrated musician Eric Dolphy recorded a now famous statement for Dutch radio at Hilversum. 'When you hear music,' he said, 'after it's over it's gone in the air. You can never capture it again.' Unaffected by the poignant simplicity of the statement, its rightness for Dolphy whose music had theory but was not a victim to theory, you might make a joke and cap-ca-cap-capture those two lines in an Akai S900 sampler to disprove impermanence and the fugitive sound. The ancient Chinese had their ideas about sound and movement, essence, time. Than Chhiao, the 10th Century Taoist philosopher, wrote: 'Sound leads back to chhi; chhi leads back to power; power leads back to the void. But the void has in it the potentiality for power. The power has in it the potentiality for chhi. Chhi has in it the potentiality for sound. One leads back to the other which has a potentiality for the other within itself. If this reversion and production were to be prolonged even the tiny noises of mosquitoes and flies would be able to reach everywhere.' It is unlikely that the buzz of a mosquito will ever be found transfixed in perfection like a buried Chinese horseman. Perhaps this is the dream of a digital restorer. In a hitherto neglected museum basement a cupboard is opened. Untouched since Victorian times it contains the preserved drone of an insect. The digital restorer gently shifts the acoustic dust and grime from this frozen moment of sound with a toothbrush. The drone grows stronger in the surrounding silence but the sound is old and fragile. It disintegrates suddenly and the digital restorer wakes with a start, sits upright in bed in a cold sweat. The young sound recordist Ludwig Koch sits under the piano with a primitive recording mechanism, stealing sound on the cusp of a new era, enveloped by music as Johannes Brahms plays above him. The young Louis Armstrong plays 'Muskrat Ramble' with his Hot Five in 1926. In 1907, the 34 year old Enrico Caruso sings 'Vesti La Giubba' from 'Pagliacci'. Brahms is lost but Armstrong and Caruso have been toothbrushed by the Australian digital restorer, Robert Parker, their ancient recordings polished to a new gleam. The restoration of sound recordings as though they were Old Master canvases proposes further manipulation of existent sound. 'Some of your new sounds are visceral, almost nauseating,' I say to Ralf Hutter of the German group Kraftwerk in December 1986. 'Over the last five years,' he says, 'you can print or design more low frequency sculpture which before wasn't possible. It would just be one big boom...or glue. That's the art of studio technology. You can sculpture the sound from 20 to 20,000 Hz. We might hammer into granite one particular sound for an enormous amount of time but then later we think in terms of film. Certain sounds we are fetishistic. One special kling then somebody else klang. Modelling this to the utmost.'Ryuichi Sakamoto, co-composer of the score for The Last Emperor and once member of the Japanese group Yellow Magic Orchestra, has suggested in interview with journalist Yukari Hirai that sound sampling should be a hyper-real or surreal experience. The sound simulation of a bullet that creates an imagined gunshot wound and transforms into a plane, then a chicken. The device that the Italian Futurists may have longed to invent.'Digital snapshots' is the name given to these fragments of sound by composer/trumpeter Jon Hassell. Fragments clipped, punched out, shot, snatched, lifted, stolen, plundered from the original recording, captured not just once in their original state but recaptured in their sampled form. Music liberated, however, from its transient smoke, steam, mist-like nature as celebrated by Eric Dolphy back in 1964 just before he entered a state in which to recapture his mastery you could only listen to the records. There are travellers who like to take a little something home with them. A chip of stone from the 1964, perhaps, before it falls down. Although the sampling or usage of existent copyright music does not cause it to physically collapse, it does raise questions of ownership. Perry Como, the man in the casual sweater, sang 'Catch a falling star and put it in your pocket, never let it fade away,' in 1958. He might have been prophesying the debates on intellectual property and creative or uncreative theft that currently vex us. In 1969 the American composer/performers La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela released a limited edition record through the Heiner Friedrich Gallery in Munich. It pointed up the problems of ownership and control that are created by fixed media. On one side of the record you are instructed to play the record at 331/3 and on the other side you are given a choice. Either listen at 331/3 or any slower speed down to 81/2 rpm. As is expected with any La Monte Young product, this is accompanied by the sternest possible copyright constraints. What the Lord giveth the Lord taketh away. Choice of how to listen is something you buy when you pay for a record. Your money gets you the privilege of ignoring the artist's intentions. You can take two copies of the same record, run through them with an electric drill, warp them on the stove, fill the grooves with fine sand and play them off-centre and out of phase half-speed on twin turntable through a Fender Vibro Champ amplifier with the vibrato on maximum and the volume on 11. Your money also buys you the privilege of playing one copy in pristine condition at the correct speed on state of the art hi-fi equipment (though if that's what you want then you've probably moved onto the passive, if potentially hyper-real medium of Compact Disc by now. Plunderphonics, as I take it, is recreational savagery. It was rap DJs from New York City who popularized the idea that recorded music was yours to plunder, yours to make new. Writing on the subject in 1984 I said, '...these cut-ups of unlikely records...were a way of tearing the associations and pre-packing from finished musical product and reconstructing it, ignoring its carefully considered intentions and restitching it into new music...the implication began to exist that consumers might eventually be able to rejig a track according to their own preferences.' Looking at that now, there is an irony to append. The records which were once deconstructed with vicious abandon, often records which had been discarded on the scrapheap of obscure music history, are now obsessively sought after by collectors. Their Nemesis has created a state of celebrity for them, perhaps implying that it is difficult to truly steal sound. Although the artifacts of the recording industry can be illegally duplicated and therefore, through loss of revenue, stolen, the hijacking and transformation of sound from those artifacts is an infinitely more complex issue, broached confrontationally and on a broad scale for the first time since the first mosquito buzz was recycled for the very first time in the void.

David Toop / London end liner notes

No Comments