Motherlode

Websites:

No

Origin:

London, Ontario, 🇨🇦

Biography:

Motherlode — Buddah’s Best from the Yonge Street School

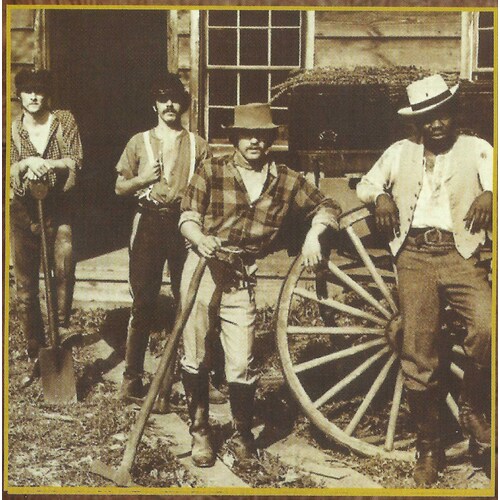

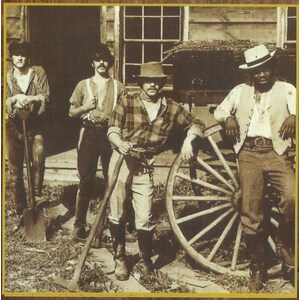

Motherlode didn’t materialize out of nowhere in 1969—they were the polished tip of a very Toronto iceberg. Sax man Steve Kennedy and keyboardist William “Smitty” Smith had paid their dues in the city’s rough-and-ready R&B circles, backing a pre-BS&T David Clayton-Thomas and then powering Grant Smith & The Power. When the Power’s relentless road work started to sap spirits, Kennedy, Smith, guitarist Ken Marco, and drummer Wayne Stone decamped to London, Ontario, determined to build a band that played their songs instead of everyone else’s. They called it Motherlode.

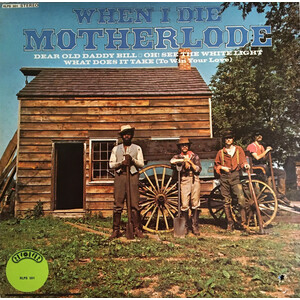

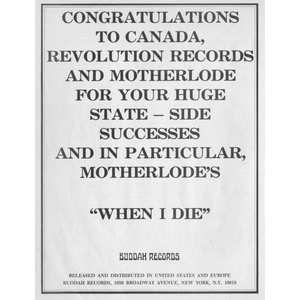

Song-first and arranger-sharp, the quartet wrote and woodshedded in Southern Ontario clubs until Revolver Records’ Mort Ross and Doug Riley opened the studio doors. The label paired Toronto savvy with New York muscle: Riley and Terry Brown produced; Dianne Brooks added velvet harmonies; and L.A. legend Carol Kaye slipped bass lines under Smith’s left-hand grooves. The result was When I Die—a gospel-soul rocker with a Hammond halo and a streetwise snap—that Buddah Records lifted into U.S. release. In the summer of ’69 it caught fire: Top 10 in Canada, Top 20 in the States, and a gold single at home. For a minute, a hornless Canadian funk-rock quartet sounded as big as a choir.

The debut album that followed (When I Die) made clear what set Motherlode apart. They were a Toronto R&B band at heart—tight, economical, arrangement-driven—but they tucked jazz touches and Sunday-morning harmonies into songs built for AM radio. Smith’s dual role (organist and, effectively, bassist) gave the band a rubbery pulse without crowding the midrange; Kennedy’s tenor and harp lit the edges; Marco’s guitar carved the hooks; Stone hit pocket, not pyrotechnics. It was a small-band sound with big-band instincts.

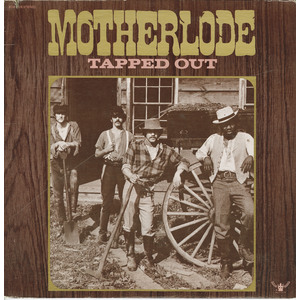

Success, however, didn’t buy stability. A softer-charting follow-up single (“Memories of a Broken Promise”) and a heavy schedule rattled the original four. By year’s end, the chemistry that made When I Die glow had drifted toward other projects—most notably Doug Riley’s Dr. Music. The twist was contractual: Revolver owned the name “Motherlode,” so the moniker stayed even when the people changed. New lineups were rushed in to deliver the second LP, Tapped Out—a patchwork of leftovers and long takes that carried the same funk-soul DNA but felt more cobbled than crafted, and radio let it slide.

What followed was a carousel of short-lived versions: gifted players from Chimo!, Leigh Ashford, Natural Gas, and beyond tried the jersey on—Breen LeBoeuf, Mike Levine, Wayne St. John, and others—cutting a handful of singles but never recreating the original spark. By mid-’71 the franchise faded, even as the core sound—keys-led, groove-forward, gospel-sweet—echoed in Toronto bands for years. A mid-’70s attempt by the founding quartet to issue “Happy People” under the Motherlode name ran aground on those same ownership rocks, and the track slipped out instead as a Kenny Marco release.

Motherlode’s legacy is larger than one perfect hit. They proved a Canadian R&B act could crack U.S. playlists before CanCon leveled the playing field, and they did it without horns or studio gimmicks—just songs, arrangements, and feel. They stitched Yorkville grit to Buddah polish, carried the Yonge Street club vocabulary into the charts, and left two albums that still punch above their weight. Spin “When I Die” today and you hear it immediately: a band built in bars, recorded by pros, and aimed—accurately—at the heart.

-Robert Williston