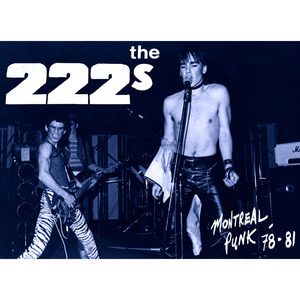

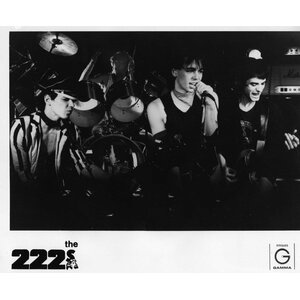

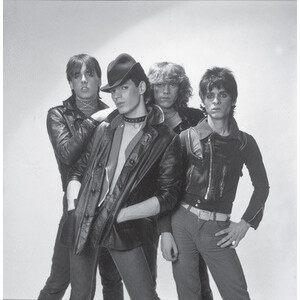

222's

Websites:

https://the222s.bandcamp.com/album/montreal-punk-78-81

Origin:

Montréal, Québec

Biography:

THE SAGA OF THE 222s

As far as anything resembling rock and roll is concerned, you probably couldn’t have found a worse place to be than Montreal in 1978. Well, okay, perhaps you might have, but for a city of roughly 2 million residents, there were remarkably few people with any interest in all but the worst musical crap of the day. Genesis, Styx, Shawn fuckin’ Phillips, this is what you heard on local radio and the bands’ kids were sporting on the backs of their pre-faded GWG jean jackets. 99.9 per cent of the local music listening population had never even heard of The Ramones, the Stooges, or the New York Dolls, and it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, because their music was simply considered too primitive – too, dare I say, rock and roll, to be taken seriously by the arena and prog rock fans of the day. Nobody seemed to “get it”, resulting in a lonely – and downright hostile - place for the few of us here who did. In those early years of punk rock, I never ventured very far from home without a thick steel chain on my person, just for those times when the constant stream of verbal abuse turned physical and I had to defend myself for the unforgivable crime of wearing peg-legged black leather pants and rejecting Kansas as a viable rock and roll option. I used that chain many more times than I ever wanted to.

This is the climate the 222’s were up against when we first got going in the spring of ’78. I had recently been expelled from my high school for doing a sexually charged, heavily Iggy-inspired performance at the annual Montreal West High School talent show with my one-off high school garage band and upsetting several parents in attendance, whose sons and daughters, apparently, were being increasingly corrupted by my profoundly negative influence upon them. My band were a huge novelty hit and won the big talent show, but I was promptly instructed to leave the school and never come back. The authorities had nothing to go on really, my grades were top notch despite a poor attendance record and a profound disinterest in studying, but so many parents had expressed concern that I was conducting drug-fueled punk rock sex orgies with the grade 9 kids that the principal and several of my teachers actually conspired to construct a plot that would convince my parents that what I really needed, more than a high school education, was psychological counseling. Lucky me. None of the accusations leveled my way were even remotely true - although the teen orgy idea was certainly not without it’s appeal – but the horrible reality of a 16 year old kid attending high school in leather pants and a torn Sex Pistols T-shirt was just too subversive for the local community at the time to accept, and I was out.

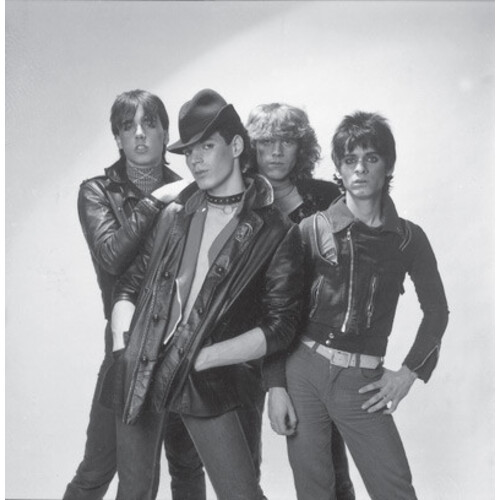

That same spring, on the other end of Montreal island, Al Clean [ Pierre Major], Louie “Louie” Rondeau, and Chris O’Bell [Christian Belleau] had just started up the 222’s with a singer named Jean Frisson – or Johnny Shivers if you feel like doing the translation. They were a sort of kid brother band to an East End rock’n’roll group named Danger, a pack of French Canadian misfits who also didn’t quite fit in to the mainstream and got branded “punk” because of it. Truth be told, Danger’s sound was much closer to traditional Rolling Stones/Faces inspired rock and roll than it was to the Damned or the Dead Boys, but in the age of Supertramp and Trooper, that was enough for those somewhat older guys to feel like kindred spirits. Besides, they were big New York Dolls fans, and so were all of the 222’s. Rest assured that in 1978, there weren’t a whole lot of Dolls fans to be found anywhere, let alone in Montreal – where they’d played only four years earlier to a crowd no larger than 100 people.

Danger actually had a record out at the time which was being played fairly regularly on French radio. The single “L’Amour Dans L’Metro” was a ballad of sorts, hardly subversive, and provided a convenient excuse for local radio programmers to pretend they were hip to this over-hyped nonsense called punk rock without actually having to play the music – which had already been overwhelmingly rejected by their listeners. Consequently, Danger could actually get gigs playing area high schools and the like, and when they did, they occasionally brought this early version of the 222’s along with them. The 222’s were universally reviled. Too loud, too outrageous, too faggy, just too far removed visually and sonically for the Yes and Doobie Brothers fans that made up the Montreal audience at the time. By that summer, Frissons had experienced enough rejection and was busy making plans to relocate to the seemingly more hospitable punk hamlet of New York City in order to make his mark on the world. Within a few months of his departure, word filtered home that the pock-marked 19 year old, who was arguably blessed with considerably more style than musical ability – had given it all up to work as a naked go-go boy in the city’s meat-packing district. True or not, and Frisson disappeared so long ago now that any word about him is difficult to confirm, with their singer now allegedly shaking his testicles for the boys over at the RamRod, the 222’s needed a new frontman. And given that there was virtually nothing locally that you could really consider a punk scene, finding someone who not only could do it, let alone who wanted to do it, promised to be a difficult and frustrating venture. After all, who the fuck in Montreal wanted to be in a punk band anyway? There were no clubs to play, no audience, only an over-abundance of ridicule to endure for your efforts.

Apparently the 222’s had looked long and hard before being introduced to me by a guy named Tracey Howe – the notably talented drummer/singer of one of Montreal’s only other “punk” bands from the era, the Normals, and whose outfit happened to share a rehearsal space on LaGauchetiere street with the singer-less 222’s.

I’d met Tracey at the one local record store in the city with the guts to place the Stooges Funhouse alongside the requisite Boston and Cheap Trick displays in their front window. 2000 Plus, as it was called, also carried import punk singles from England and the U.S, and by default, had become a meeting place of sorts for the few hundred people in the city who dug, for lack of a better term, punk rock. Hey, at least they had a bulletin board in the store where people looking to form bands could post their ads. On my end, I was just thrilled to discover that other people in town with similar tastes actually existed, and better, that some of ‘em even wanted to start bands. You know, real bands, bands who wrote their own songs and maybe even aspired to be the next big thing – which certainly was the case with the 222’s, who, throughout our career, never quite understood why we never got our shot at being the next, uh… Generation X perhaps? At the time, outside of this very small punk scene which was gradually developing, nobody played their own material here. In the English milieu, it was all cover bands doing Cheap Trick, George Thorogood, and/or Rush covers, whereas on the French side of things the bands who were actively making records and playing around the province were simply too shitty to even consider - certainly a far cry from anything the 222’s or any of us so-called punks might have labeled rock and roll. That whole scene had nothing to do with us – and wanted nothing to do with us – which was just fine, of course. You know, so long as one was happy being completely ignored by the media, the general public, or anyone with the wherewithal who might be capable of putting out your records.

By the time I joined 222’s in the fall of ’78 a bona fide local punk scene had developed, with a few other bands, like the Normals, Lorne Ranger, the Chromosomes, and a little later, the Electric Vomit, all finding the occasional gig at loft parties and the like. One venue, 364 Saint Paul street, actually managed to put on more than one punk gig before being shut down. These were always what you might call “underground” affairs, rarely attended by more than a couple hundred people at best, but at least it was something. The scene even had it’s own fanzine, Surfin’ Bird, which treated us local punk outfits as something other than the irrelevant yet vaguely threatening joke the rest of the Montreal media saw us as. It wasn’t much compared to the scenes going down in London, L.A, and New York, but again, it was something.

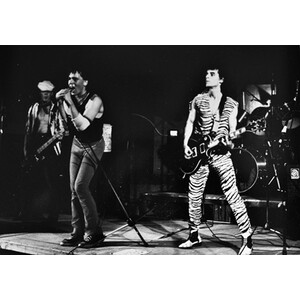

The problem for the 222’s, however, is that we didn’t really fit into this little punk scene either. For starters, Pierre, Louie and Belleau were all fairly capable musicians and weren’t particularly ashamed of the fact either, resulting in a lot of hostility being sent our way by many of the local “punks” who’d decided that carefully crafted songs and musicianship beyond the level of Sid Vicious was antithetical to their carefully studied punk stance. Further, our immediate roots were as much in the early ‘70s glam tradition as they were in the spirit of the Ramones or the Pistols, bands which we viewed as a natural extension of the Dolls/Stooges/Alice Cooper school we’d all been weaned on. Exasperating the situation, our first manager, Pyer Desrochers, was an outrageously arrogant boutique owner a la Malcolm McClaren who fashioned us in Chairman Mao T-shirts, day-glo orange leather, zebra skin pants, and a whole lot of accessories which suggested we were as concerned about our visual appearance as we were with the “punk revolution.” And, of course, we were. In contrast to the Chromosomes, whose primary focus seemed to be fixated on heroin, or the Normals, who I vaguely recall as having a somewhat political bent, the 222’s were profoundly obsessed with sex, and rock and roll was, needless to say, a very convenient vehicle in which to lure the necessary participants required to engage in the relatively debaucherous sexual activities most of us were interested in. Not only were the 222’s, from fairly early on in the game, capable of drawing an actual, and increasingly diverse, crowd to our relatively sporadic gigs, but there were always lots of girls at our shows – two things, I imagine, which also helped nurture much of the growing animosity/jealousy between our band and so many among the largely male-dominated Montreal punk scene. That said, I suspect our own undeniable arrogance and sense of superiority didn’t help the situation much either.

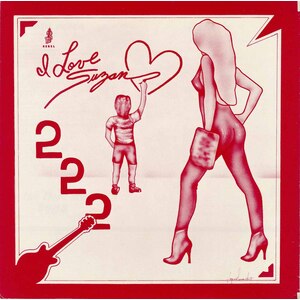

Nevertheless, like it or not, we were all sort of stuck with one another. If the 222’s didn’t have much in common with, say, the Chromosomes, we had even less in common with the mainstream acts of the day. Consequently, for the first year or so of our existence, we often all wound up on the same bills together, and these gigs rarely went well for the 222’s. In early 1979 we played a gig at McGill University called The First Montreal Punk Fest - or something along those lines - with The Chromosomes, the Electric Vomit, The Unknowns, and no doubt a couple other bands whose names I can no longer recall. Being the only local band to have an actual 45 single out, a DIY effort called I Love Suzan b/w The First Studio Bomb, and in recognition of our developing notoriety, the 222’s were billed as the headliners – although that meant very little and we knew it. The gig brought out close to 800 people, which by our little scene’s standards was a huge fuckin’ audience – even if a good half of attendees were curious frat boys and the like who only came out to marvel and jeer the punk rock freaks. When the 222’s finally came on at the end of the night, our good friends the Chromosomes, in the true punk spirit of cooperation, sabotaged our equipment, and while we struggled to try and figure out why our amps weren’t working, stood bravely in the shadows throwing garbage and beer bottles at us. This was all the encouragement the restless drunken frat boys needed to really get in on the action. The 222’s, wrestling with our gear, attired in our glam/punk hybrid fashions and somewhat even pleased to find ourselves objectionable to these fuckin’ philistines, were literally bombarded with spit [of course] and beer bottles. [Beer bottles being things we would eventually get very used to being hurled at us before finally calling it a day in ’81.] Overwhelmed and too inexperienced and/or stupid to simply tell ‘em all to go fuck themselves and leave the stage, I instead took my cue from Iggy’s Metallic KO record and taunted the audience as best as my 16 year old intellect could muster. A bad idea to be sure. As things got increasingly ugly, somebody decided it a good idea to cut all power running to the stage and turn on the house lights. A riot of sorts ensued, causing an untold amount of damage to the university and surrounding area, with the end result being anything labeled punk was promptly banned from pretty well every possible venue in the city.

We continued gigging as best we could after the McGill riot, but opportunities to play anywhere were few and far between. By the spring of ’79, our original manager, Pyer Desrochers, grew bored with us and our “careers” began to be handled by the guy who’d funded our I Love Suzan/First Studio Bomb single, Francois Doyon. Doyon was something else entirely, a hedonistic, distinctly funny-looking hustler who’d recently come back to Montreal after being chased out of Los Angeles by U.S Immigration, but not before being transformed by the burgeoning L.A. punk scene of the Germs, Screamers, and the Wierdo’s. The problem with Doyon, however, is that he knew little more about the music industry than the rest of us. Later, when we began to believe there was no good reason why we shouldn’t be signed to a major label, a thoroughly oblivious Doyon would show up in executive offices wearing knee high rubber fly fishing boots and denim hot pants, almost always with at least one testicle hanging out the side, trying to convince these straights that the music you’re hearing on this CD was the future of the Canadian music industry. Most – but not all – of the industry types he came in contact with took him about as seriously as they took the band –which is to say, not at all.

Still, Doyon had plenty of energy and an unwavering commitment to the concept that the 222’s, if only given a chance, might still be able to rise to the toppermost of the poppermost of the music world. Over the years he would arrange to get us support slots on small tours with The Stranglers, Simple Minds, The Professionals and other bigger groups, as well as setting us up at Max’s Kansas City in New York and a host of other vaguely “prestigious” punk venues around the Northeastern U.S and Canada. Still, by the summer of 1979, there remained preciously few venues where we could play in Montreal – or anywhere for that matter. Thanks, however, to our numerous appearances on a local cable TV show called Musivideo, which was the brain child of Doyon’s partner in crime, a perversely strange fellow named Marc Fontaine, the 222’s had developed a large, loyal following in the city, to the point where we could generally count on drawing several hundred people to our gigs. In Toronto, where they had a significantly healthier punk scene, we would do even better. Translating that modest popularity in to a record deal or anything substantial, of course, would prove to be a considerably more difficult endeavor.

By the fall of 1979 our bassist, Christian Belleau, lost faith in our band’s ability to go anywhere and abruptly quit the group. We replaced him with a juvenile delinquent I’d known back in high school named Joe Ceratto. Joe, like Pierre Major and myself, was a teenage high school drop-out with few interests outside of chicks and rock and roll. He came from well below the tracks and sported ‘tude to boot. Having spent the summer of ’77 in NYC, doing the whole CBGB’s thang, he knew what the 222’s were shooting for and soon fit in with us perfectly.

Shortly thereafter, the three of us, Joe, Pierre, and I, moved in to the rehearsal space Pierre had found in Montreal’s Little Burgundy district – at the time a largely forgotten industrial area in the slums just south of the downtown core. We were poor. There was no hot water and we bathed in a small steel wash tub we kept in the makeshift kitchen. Pierre and Joe had been deemed psychologically unfit to ever hold down jobs by their respective social workers, and were awarded approximately $125 a month in welfare benefits as a result. Not that there was a chance in hell that anybody would have employed them anyway. The 222’s, always extremely style-conscious, wore the same clothes on the street as we did at gigs, and even if it did mark us for ridicule and derision, to wear anything else would have been a betrayal of our principles. Besides, getting a job or anything like that, apart from being degrading, was of little concern to us. After all, we were sure our destiny was that of fabulously wealthy punk rock stars. We didn’t know anything. Louie “Louie” Rondeau, who was somewhat older and always had it a little more together than the rest of us, did manage to land a part-time job in a liquor store and was able to keep his own modest apartment. I alternated between checking bags in an indie record store, whose hippie owners saw me as a charming curiosity, and collecting unemployment insurance. We were a relatively pathetic lot who subsisted primarily on the food that friends and fans would bring to our locale, which at its best was a den of iniquity and a weekend crash pad for seemingly every dog-collared kid who’d stayed out too late to catch their bus back home to the ‘burbs. Eventually we were evicted from the five-room, 1400 square foot former office space because between the four of us and our manager we couldn’t find the $120 rent one month. Like I say, we were something of a pathetic lot.

Come 1980, with the 222’s and what was left of the “official” local punk scene at greater odds than ever before, we started playing pretty well anywhere that would have us. Because we could draw, we’d get gigs in bars and brasseries that heretofore only hired cover bands, playing our modest 20 song repertoire over and over, doing as many as four forty minute sets a night for audiences who often as not detested us. Fights would consistently break out between the fans who’d come to see us and the AC/DC rocker types who inhabited these shitholes on a regular basis. Nevertheless, we continued playing these joints because, essentially, that’s all there was. It stunk, but we had absolutely nothing better to do with our lives, and if we were lucky, a weekend playing in one of these bars might net us a cool $75 each. Assuming, of course, that we could walk away without paying for the inevitable strew of broken mic stands and damaged stage monitors we were forever leaving in our wake.

Around this time, the 222’s attracted the affections of Teenage Head’s somewhat dubious manager, Jack Morrow - a man rumoured to have an unhealthy interest in good-looking teenage boys but also possessing all the right Toronto music biz connections which we believed might’ve been able to make mega-stars out of us yet. Teenage Head were an absolutely amazing band in 1980, full of confidence no doubt inspired by having recently seen their sophomore record, Frantic City, go gold in Canada, and their ability to regularly draw crowds upwards of 1000 people on any given night – in Ontario at least. These guys were the best, and the 222’s absolutely adored them.

For most of 1980 Morrow would regularly slap the 222’s on to the Canadian university tours the Head were always doing, in spite of the fact that much of their good time college boy audience took exception to our sound and appearance, and, as per usual, were keen on hurling ever more spit and beer bottles our way. Of course, not everybody hated us, and in fact, by the end of 1980 we had managed to build ourselves a pretty solid reputation in central Canada, of sex-obsessed weirdo’s mind you, but also as a pretty decent little band. Still, there wasn’t a chance in hell of our landing a record deal, or for that matter, ever earning enough money to try and put out another indie single. We had pretty well stagnated, the initial “punk” thing we’d been associated with a couple of years earlier was effectively dead by then, with hardcore bands like Discharge and the Angelic Upstarts taking the lead in what we saw as a tired, increasingly violent, and unwelcoming scene. We could still draw an audience, but we were pretty well fucked, and kind of new it. It was closing in on three years after the release of I Love Suzan/The First Studio Bomb and we still hadn’t even gotten it together to make another 45 single – let alone a full record.

We would venture off to do the occasional gigs in the Northeastern US and Ontario, as well as do a series of month-long residencies at a little bar on Saint-Catherine street in Montreal called Station 10, but it was really beginning to feel like the wind had been taken out of our sails.

Somewhere around this time our long-suffering manager Frank Doyon came into contact with some local mobsters anxious to flex their muscles in the Quebecois music biz. Given our options at the time, Doyon was quick to put the 222’s up for grabs, and the gangsters, to my personal surprise at least, initially took to us with a vengeance. We’d been doing a cover of the 1960s French garage hit, La Poupee Qui Fait, in our live set for well over a year at that time and the thugs were positive they’d be able to use their, ahem, influence, to turn the song into a regional hit and successfully market us as some kind of fucked up Quebecois teenybopper band. I didn’t care. I liked the idea of becoming a local teen sensation to begin with, and fuck, since we weren’t about to alter our shtick in any way to be more accommodating to this decidedly retarded market, like, why not? Besides, after three years of tirelessly trying to sell our act, the mobsters were the first and only people who actually offered to fund a record for us. But it didn’t work out very well. We wound up recording two songs for them, Come to Me Cold, and La Poupee Qui Fait Non, in the basement of the head criminal’s house way out in the bowels of Laval, Quebec, a particularly gross and tacky suburb just north of Montreal.

For starters, as soon as we got in there to do the basic tracks, the thugs decided suddenly that they were music producers and that this was going to be their record. Further, they soon came to realize that they hated my singing – and by extension, me – but that lobbying to kick me out of my own band might represent a few problems in their marketing of the 222’s as Quebec teen sensations. And Pierre Major, a truly brilliant guitarist but decidedly somewhat unbalanced individual possessing one fuck of a fiery temper, [rightly] got it into his head that these guys were the devil and decided he would have absolutely nothing to do with their bullshit, deliberately challenging them on even the most trivial details. After several days of non-stop fighting, the thugs decided they were through with being polite to the 222’s, invited a couple of us upstairs to “discuss” the situation, produced a handgun and placed it on to the kitchen table in front of us, informing us in no uncertain terms that the fighting was over, and that we would be wise to do as we were told from here on in. Determining that living might be somewhat more important than the quality of this bullshit record we were making, we agreed that yes, the fighting was indeed over, and finished off the day in a state of fear, never returning to see those fuckers again. Several months later, the 222’s long-awaited follow up record, La Poupee Qui Fait Non, was released. It was an unspeakably terrible record. The thugs had replaced my dreaded voice in the choruses with that of the head crook and his obese sister, singing with the intent of sounding like the spoiled little girl addressed in the songs lyrics. You couldn’t have gotten more lame. Worse, the record started getting a fair amount of airplay in Quebec and turned in to a minor regional hit. Words cannot explain how ashamed I was of this piece of shit, and yes, still am, which is why I still can’t bring myself to include it on the album you’re currently holding in your hands. You’ve got the demo version on this instead.

That record effectively brought about the final demise of our band. Our credibility was now pretty well shot locally, and I, at least, knew, and fully understood, why. Nobody was stepping forth to allow us the opportunity to make a “real” 222’s record and redeem ourselves, and anyway, by this stage of the game several members of the band had pretty well resigned themselves that the 222’s, with me as the singer, at least, were never going to go anywhere. It had been three solid years of disappointments, capped off by an offer from Stiff Little Fingers to tour the UK with them, which we found ourselves unable to do for lack of funds. In November of 1981, after a good year of bickering between myself and the other guys in the band – who, defeated, were leaning towards taking the 222’s in a more mainstream musical direction that I wanted no part of – finally called it a day. And nobody really much cared or noticed.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The tracks on this CD are primarily comprised of demo’s we did in the summer of 1979, along with a few live tracks from ’78 and again in 1981, during our Quebecois wannabe teen sensation phase. Most, if not all, of the recordings on this disc were thought lost forever until early 2005, when I by chance ran into a Montreal radio disc jockey named Mike Biscott who promptly informed me that he still had copies of pretty well everything we’d ever recorded and that the stuff was, well, actually pretty good. Given that the past few years seem to have brought a bizarre resurgence of interest in the 222’s, well, uh, here you go. Enjoy.

-Chris Barry

Chris Barry: vocals

Pierre Major: guitar

Joe Cerratto: bass

Louie "Louie" Rondeau: drums