Information/Write-up

Harry Rusk was born on July 5, 1937, to Edward and Mary Etsuka on a trapline near Fort Nelson, British Columbia, in the tiny Kahntah-Slavey First Nations hamlet where radio was the only link to the outside world. Tuberculosis cast a long shadow over his early life: his brother died when Harry was three, his father when he was six, and at twelve he too was flown to Edmonton’s Charles Camsell Indian Hospital, where he remained from 1949 to 1953. In the ward the children called “death row,” he met country star Hank Snow during a special hospital visit on June 13, 1952, and Snow’s encouragement — “always look up” — became the guiding line of his life. His mother later bought him his first guitar with money earned sewing handmade moccasins and slippers, and though she died of tuberculosis in 1953, she left him with a steadfast belief in music that never wavered.

Returning to Fort Nelson, Rusk began hosting “Country Time With Harry Rusk” on the local CHFN Armed Forces station and led the Harry Rusk Dance Band at nearly every hall, reserve gathering, and community event from 1955 to 1963. In those years he briefly joined the Royal Ordnance Corps, stationed at Maskwa Garrison and then in Vancouver, before returning to music full-time and spending a year on the Vancouver circuit. In 1965 he moved to Edmonton, at first playing with Jimmy Arthur Ordge, who encouraged him to strike out on his own and promised to give him references. This led Rusk to form his first long-running group, Harry Rusk and the Tradewinds — a name inspired by a Hawaiian band he worked with during a 1970 engagement in Honolulu, and which he officially registered after his return to Alberta.

When he arrived in Edmonton, he was searching for a break. “I figured I might as well start at the top — only a ditch digger starts at the top,” he joked in one interview, recalling how he decided to call Gaby Haas directly after watching CFRN’s The Noon Show on television. He phoned Haas — without ever visiting the music store — and asked how to get on the program. Haas told him he would need to join the Musicians’ Union and “get a yellow card,” advice Rusk initially suspected might be a prank. He went anyway, met union officer Eddie Baines, and began a lifelong friendship that lasted decades. Within a week Haas remembered him on the phone and said, “Bring your guitar and be at the studio at 11:30 next Tuesday.” From that moment Rusk became a regular on The Noon Show, appeared on Lil Ole Opry, and was invited to perform on The Chuck Wagon Show, CTV’s Country Music Hall of Fame, CBC’s Don Messer’s Jubilee and Country Time, and numerous ITV holiday specials. His television career soon extended beyond Alberta as he moved to Toronto for additional work, then to Halifax for CBC’s Don Messer’s Jubilee, before returning to Toronto for more national broadcasts. Haas remained one of his closest supporters for decades, and Rusk told interviewers that Haas once joked to a reporter, “Harry isn’t a great musician, isn’t a great singer — but I told Robert Goulet and Lorne Cardinal that too,” a line Rusk loved to repeat and insisted be printed exactly as said.

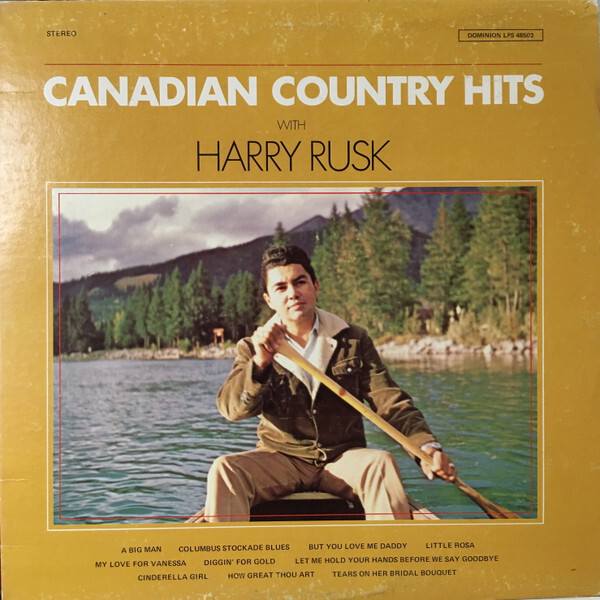

His recording career began in 1967 at Joe Kozak’s Studio in Edmonton, the beginning of a long and trusted partnership with Kozak, whom Rusk affectionately called “a great engineer, great singer, great musician,” and with whom he recorded many of his early albums. This was followed by a long string of independent releases and originals such as “Digging for Gold,” “Rose of Mexico,” and “The Red Man and the Train,” the latter eventually becoming one of his signature songs. He later recalled that at one Grand Ole Opry appearance he received an encore for it, a rarity in Opry history and an honour he said only Hank Williams had been granted before him.

Another defining moment came in 1969 at the Calgary Stampede, when Snow recognized him as the boy from the Camsell ward. Snow asked him to send new recordings, and on June 13, 1972 — exactly twenty years to the day after their meeting — invited him to Nashville to appear on the Grand Ole Opry and Ernest Tubb’s Midnight Jamboree. Rusk often explained that his mission to reach the Opry began in the 1950s, when he grew tired of being told he would “never make it,” and that seeing Snow on the cover of a 1955 songbook convinced him to make Nashville his life’s goal. He recorded “In Peace Extend Your Hand” and “If We Never Meet Again” in Nashville with Snow’s Rainbow Ranch Boys, and Snow later told him he was the only artist he had ever played lead guitar for. From 1972 through 1994 Rusk became the first Dene performer — and, as he often noted, the first full-blooded Treaty Indian — and by most accounts the first Indigenous Canadian artist to stand on the Opry stage, often performing the very songs he had once learned on a wind-up gramophone near Fort Nelson.

Rusk’s songwriting often came in sudden flashes. He wrote “Remember, I’ll Always Love You” after seeing a man weeping at an Edmonton intersection, pulling into the A&W at 118th Avenue and Fort Road to scribble the lyrics on the nearest surface — “I wrote it on a toilet seat,” he laughed. “Leaving Footprints in the Snow” came after meeting two childhood sweethearts who had reunited and become engaged at Lake Louise the night before; he stepped outside, saw the snow-covered mountains, walked to his car, and the entire song arrived at once. His 1970s travels to Hawaii inspired “Hawaiian Cowboy,” and “The Red Man and the Train” remained his own favourite, a song he continued receiving royalties for decades later.

His career stretched across more than fifty-five albums of country, gospel, bluegrass, and inspirational music, many sold directly at concerts in the northern and rural circuits where he was most beloved. Overseas tours carried him to Holland, Italy, England, Norway, Germany, Poland, Austria, Sweden, Israel, Cuba, Mexico, and across the United States. He appeared at CFL games, major hotels and theatres, and countless community halls. Through all of it, he maintained that the most important turning point in his life came not onstage but in 1975, when his son survived a frightening illness and he found his faith; from that moment on he devoted his voice to gospel. “The greatest award,” he often said, “was when I received Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior.”

In 1981 he met his future wife, Gladys, at a church in Edmonton when she announced she would be singing “in the key of C,” a line that became a family joke; she soon joined him in performance, including in Nashville and on the Opry stage. The pair toured for decades through concerts, schools, legends shows, reserves, churches, and community centres across Canada and the United States. Gladys later said that everywhere they travelled someone stepped forward to share a memory of Harry’s music: “I remember him from…” became a constant refrain. Their partnership continued into the 2010s, and in 2014 Rusk recorded with members of Snow’s Rainbow Ranch Boys on the track “Harry Rusk Plays Guitar.”

Rusk received the Alberta Government Achievement Award (1976), British Columbia’s Government Recognition (1977), the Queen’s 25th Anniversary Medal (1978), the Hank Snow Country Music Hall of Fame induction (1996), the Bev Munro Traditional Country Music Legend Award (2010), and numerous religious ordinations. In 2015 he became the first Canadian ever honoured with the National Traditional Country Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, recognizing more than six decades of work keeping traditional country music alive. His life inspired two books and the 1986 television film Beyond the Bend in the River, in which he appeared as himself.

Harry Rusk died on March 20, 2025, at his Rainbow Ranch in Carrot Creek, Alberta. His journey — from a remote Kahntah trapline and a four-year stay in the Camsell hospital to Ernest Tubb’s Midnight Jamboree, the stages of Nashville, and a lifetime spent singing to communities across Canada — remains one of Canada’s great northern stories of resilience, faith, and music born from hardship and carried into hope.

-Robert Williston

No Comments