Information/Write-up

A defining voice in Quebec’s early 1960s twist and yé-yé boom, Guy Roger rose quickly to prominence with his blend of charm, rhythm, and crowd-pleasing style. Born in Montreal on March 24, 1936, Roger studied at École de La Mennais and began performing in amateur competitions before signing with Apex Records in 1960.

His breakthrough came with the hit single “Tu peux la prendre”, which made him one of the first French-Canadian singers associated with the twist craze. The track appeared on his 1962 debut LP Monsieur Twist (Apex ALF 1541), a vibrant collection of dancefloor-ready adaptations and originals that aligned him with the era’s youthful energy and burgeoning pop scene.

With his slicked-back look, upbeat rhythms, and smooth voice, Roger earned comparisons to contemporaries like Yvan Daniel and André Sylvain. He was a fixture in fashionable Montreal cabarets such as La Page Blanche and Chez Émile, and even briefly hosted radio and television programs, including Vive la vie on CKVL in 1967.

Despite his success, Roger remained wary of being pigeonholed by trends. Though dubbed “Monsieur Yé Yé” by the press, he bristled at the label, emphasizing instead his vocal individuality and ambition to interpret a wide range of material. “The twist passed quickly,” he later said. “I have a voice that people recognize — that doesn’t sound like everyone else’s.”

His 1965 self-titled album Guy Roger (Carnaval C-489) reflected this evolution, moving toward more standard chanson and crooner fare. The transition was met with mixed critical response, with some noting a return to his early sentimental style à la Parlez-moi d’amour.

By the late 1960s, as musical fashions continued to shift, Roger faced the challenge of retaining a young audience. Candid about the music industry's barriers, he noted: “It’s always the same people who get the biggest slice of the pie.” Around 1968, he made the difficult decision to step back from performing, stating simply, “My job is my reason for living, but I know I could never truly quit — even if I tried.”

He turned instead to family life and entrepreneurship. Settling in the Côte-des-Neiges district of Montreal with his wife Barbara and children, Roger became co-owner of Le Viking, a cabaret and discothèque on Boulevard des Laurentides. Though he left the stage, he remained proud of his legacy as one of the few Quebec artists to break through during a time dominated by American acts.

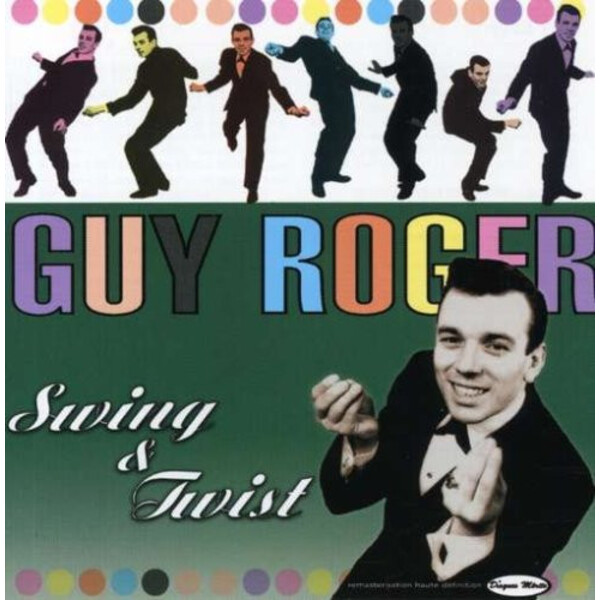

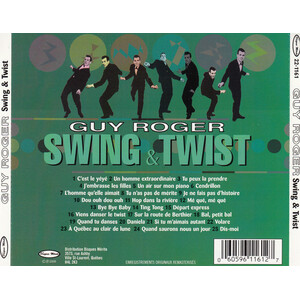

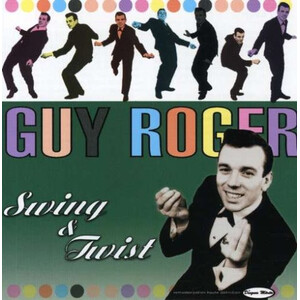

In 2000, his recordings were reissued on CD under the title Swing & Twist (Disques Mérite 22-1161), reintroducing his vibrant performances to a new generation. Tracks like Tu peux la prendre, L’homme qu’elle aimait, and Bye Bye Baby still showcase the playful energy and vocal personality that made him a standout in Quebec’s early pop history.

-Robert Williston

Liner notes:

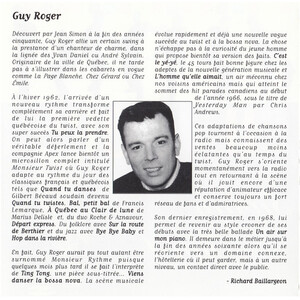

Découvert par Jean Simon à la fin des années cinquante, Guy Roger allie un certain swing à la prestance d’un chanteur de charme, dans la lignée des Yvan Daniel ou André Sylvain. Originaire de la ville de Québec, il ne tarde pas à s’illustrer dans les cabarets en vogue comme La Page Blanche, Chez Gérard ou Chez Émile.

À l’hiver 1962, l’arrivée d’un nouveau rythme transforme complètement sa carrière et fait de lui la première vedette québécoise du twist, avec son super succès Tu peux la prendre. On peut alors parler d’un véritable déferlement et la compagnie Apex lance bientôt un microsillon complet intitulé Monsieur Twist où Guy s’amuse à adapter ce rythme au goût des classiques francophones du temps, tels que Quand vous dansiez, Tenez-vous bien, Au petit bal du samedi soir. À Québec au Clair de lune de Martial Delisle et Et pourtant de Charles Aznavour. Ce disque est un énorme succès. Sur la route des vacances avec Bye Bye Baby et Hop dans la rivière.

Guy Roger

Discovered by Jean Simon in the late 1950s, Guy Roger combined a certain swing with the presence of a charming crooner, in the vein of Yvan Daniel or André Sylvain. Originally from the city of Quebec, he quickly made a name for himself in popular cabarets like La Page Blanche, Chez Gérard, and Chez Émile.

In the winter of 1962, the arrival of a new rhythm completely transformed his career and made him the first Quebec star of the twist, with his smash hit Tu peux la prendre ("You Can Have Her"). It marked a real turning point, and the Apex label soon released a full LP titled Monsieur Twist, where Guy had fun adapting the rhythm to popular French classics of the time, such as Quand vous dansiez, Tenez-vous bien, Au petit bal du samedi soir, À Québec au Clair de lune by Martial Delisle, and Et pourtant by Charles Aznavour. This record was a huge success, as were Sur la route des vacances, Bye Bye Baby, and Hop dans la rivière.

At the same time, Guy Roger stayed closely attuned to developments in popular music. As the bossa nova began to make waves, he was among the first to sing it in French. The music scene was evolving quickly, and a new wave was already following the twist and bossa nova. This did not escape the curiosity of the young artist, who soon offered his own take: yé-yé. His 45s were well received by the new generation of music fans, particularly L’homme qu’elle aimait (“The Man She Loved”), a little-known tune in the U.S. that reached the top of the Canadian charts in early 1966 under its original English title Yesterday Man by Chris Andrews.

These adaptations of pop songs often leaned toward musical comedy, offering Guy Roger many opportunities to perform on stage. In 1967, he even became the official host of the show Bon dimanche on Radio-Canada television, later hosting several other similar programs across the network, building up a large base of admirers along the way.

His final recording, in 1968, saw him return to the crooner style of his early days. Backed by a large orchestra conducted by maestro François Cousineau, he paid tribute to the golden age of swing. This recording, of exceptional quality, remained unreleased—until now. It is fortunate that this forgotten LP can finally be heard, appreciated, and celebrated as it deserves to be, thanks to this reissue.

— Richard Baillargeon

No Comments