Information/Write-up

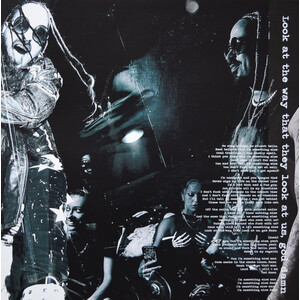

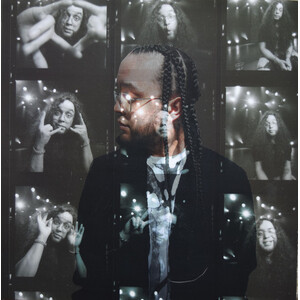

It’s impossible to take your eyes off of Snotty Nose Rez Kids (SNRK). I mean that figuratively — the boldly political Indigenous duo has been pushing boundaries and drawing attention with explosive, incendiary hip hop since the band debuted in 2017 — but it’s literal, too. When I meet them at Soundhouse Studios in Vancouver, B.C., the first thing that draws my attention is their one-of-a-kind look.

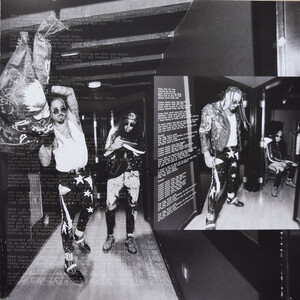

As we chat on the studio couch between rehearsal sessions, Darren “Young D” Metz wears a Nirvana T-shirt and gold chains, his chest-length curly hair tucked into a snapback; Quinton “Yung Trybez” Nyce — armoured in leather, studs and metal — is a futurist mashup of an old-school ’70s punk and a classic ’90s rapper.

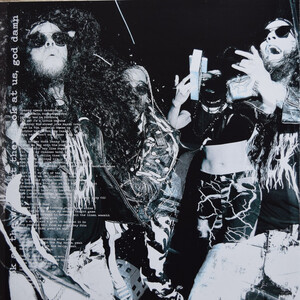

Their genre-bending style belies a dedication to pushing the envelope that’s made even clearer by their no-holds-barred music. They’ve carved their niche in the rap community by spearheading a movement that uses punk-inflected vocals and synth-y, high-powered instrumentation to drive home lyrics about Indigenous protest, resilience and pride.

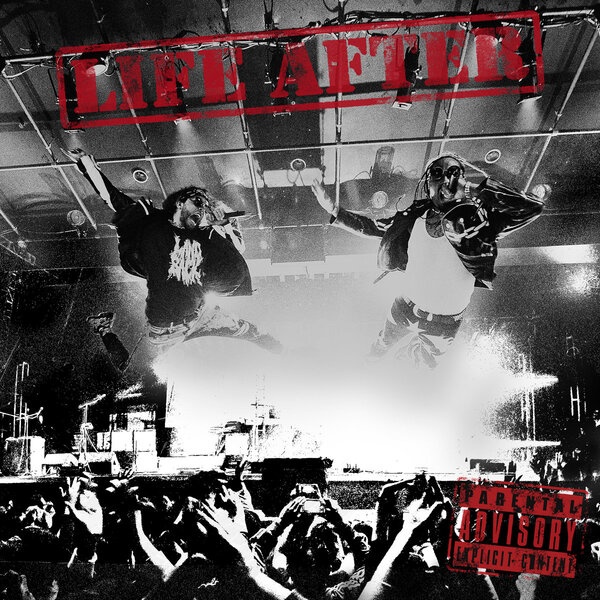

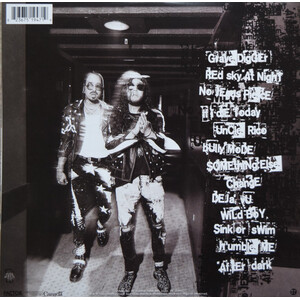

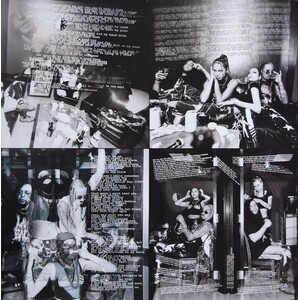

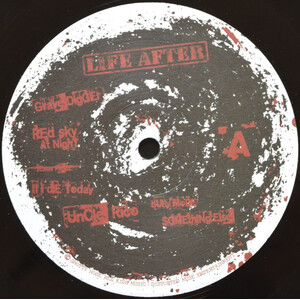

They’re getting ready to tour their brand-new album, Life After, which marks a new era for the duo.

“We did a lot of experimentation on this album,” says Metz. “We got really experimental with our songs, just trying new things, trying to get with the times, I guess.”

Their earlier music draws heavily from ’90s hip hop, but on this new album, they’ve delved headfirst into heavy-hitting, gritty futurism. Synths soar over distorted, glitchy production and ferociously non-stop bars, and tracks draw clear influence from punk, alt-rap and noise to craft a darkly badass ambiance.

“We’re always looking to go outside the norm, but I try to make something that’s authentic to us, and we try not to ride waves or follow trends — we just stay true to ourselves. We’re not shitting on people that do that, though — you do you,” adds Nyce.

The album was inspired in part by the duo’s personal struggles throughout the pandemic. Besides being a difficult year for everyone in so-called Canada, the past 18 months have also shed new light on some of the horrific anti-Indigenous genocidal acts that shaped this country — and, sometimes, it feels like nothing is changing.

“Before we even think of reconciliation, you got to focus on the word before that, which is the truth,” Metz says. “And a lot of people still can’t accept it. Although, I will say, a lot of people are being like, ‘Holy fuck, I can’t imagine.’ We have some like homies that are fathers, and who are white, and and they’re just like, ‘Man, I couldn’t fucking imagine having my two little boys taken’.”

“Like, last one closed in 1996,” he continues, pain palpable in his voice — he’s talking about residential schools, the institutions Canada developed as tools of genocide against Indigenous families. Over the past year, numerous unmarked graves were uncovered under residential schools across the country.

“And we always say, this brought up things that we already knew, like, we’ve been knowing this, and we’ve been saying these things. But it wasn’t until there was that physical evidence that people got it.”

As one of the biggest voices in the Indigenous music scene, SNRK have had a significant role in bringing Indigenous issues into the spotlight; they’ve never shied away from using their music to centre both Indigenous struggle and Indigenous success. They can play a sold-out show in any city in the country, and you’d be hard-pressed to find an Indigenous kid anywhere in so-called Canada who doesn’t know their name, so they never miss a chance to give credit to the community that raised them and supports them to this day. But with this deep connection to the Indigenous community also comes a kind of responsibility and accountability that white rappers never have to contend with.

“We’re held to a certain standard,” says Nyce. “And we are held accountable by our community. With the stuff that we say, the stuff that we talk about, the stuff we write about, we’re held to a higher standard than just your average white rapper. We can’t be talking about women, drugs, money and all this kind of stuff — even though, of course, that’s not who we are, but you can’t say that kind of stuff because of the standards that our community pulls us to. And I’m okay with that — that’s cool to me. As long as I can make everybody comfortable with listening to our music, I’d rather have that than anything else.”

“Yeah, honestly, I would rather have that kind of pressure within our community wanting us to succeed,” adds Metz. “I’d rather have that pressure. You just want to set a good example. But at the same time, we will say we’re only human. We’re not gonna sit around and put ourselves on a pedestal like we’re Mr. Perfect. We’re not.”

“We’re two cis Native men,” adds Nyce. “We can always speak from our own contexts, but we do speak for a larger body of people, so we have to make sure that we’re respectful and that our music can be accessed by them.”

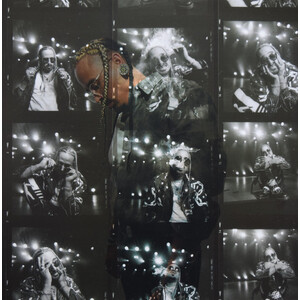

And they’ve risen to the challenge. With lyrics that preach about radical protest, Indigenous community, police violence and decolonial spirituality with undeniable fire and soul, they’ve become role models for the next generation of Indigenous artists.

“I just want people to know that anything’s possible if you put your mind to it,” says Nyce. “When we talked about being vulnerable on this album, we’re talking about some serious shit that we went through growing up, and we’re letting people know, like, there was life after that. You know, there’s life through the trauma. All you got to do is just keep your head up and things will get better.”

“Like, our JUNO nom., in 2019, we recorded that in the spare room of his house. And we’re so proud of this album too,” says Metz. “When it came to mental health, I really struggled at some points during this pandemic — I wanted to give up on everything. And through the grace of the Creator and the family, and my brother, I was able to keep going. So this album is honestly one of my proudest moments. Like, we fucking made it, you know what I mean? This is probably one of my proudest moments.

“It’s okay to be vulnerable and tell your story. Just love yourself, y’know? Why touch what Creator put his paintbrush on? When it’s all said and done, when we have grey hair, when we’re grandpas, my biggest wish is that, for the next generation that’s coming up, I don’t want them to be like ‘Yo, I want to be like Snotty Nose Rez Kids’ — I want them to say ‘They inspired me to be myself, unapologetically’.”

-Rayne Fisher-Quann

No Comments