Information/Write-up

In the song "Matapedia", from Kate and Anna McGarrigle's 1996 album of the same name, Kate describes a tense meeting between her then-17-year-old daughter, Martha, and an older man, presumably Martha's father, Loudon Wainwright. Kate notes how "he looked her in the eyes/ Just like a boy of 19 would do." And even though Martha is facing someone who is a stranger, relative, and musical forebear, "she was not afraid/No, she was not afraid." It's only one of innumerable songs the Wainwright clan has written about each other, but nine years later, "Matapedia" sounds particularly prescient. Martha Wainwright's fearlessness has not abated with age, but has found an outlet in the family business.

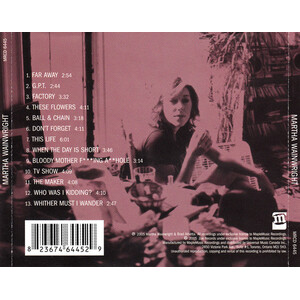

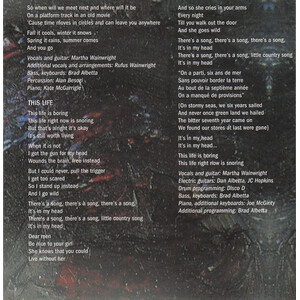

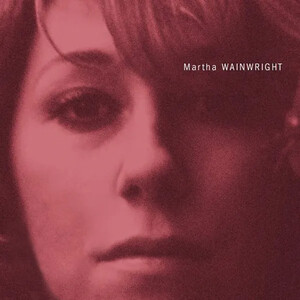

Like her parents and brother, Martha writes candidly and often hostilely about the people around her, be they lovers, friends, or family. She has her father's name (as well as an album cover that mimics his 1975 Unrequited), is blessed with her mother's gracefully lilting voice, and borrows her older brother Rufus's witty frankness. She generally composes in the 70s folk singer-songwriter mode: Every song seems to have originated with only her voice and acoustic guitar. Some songs remain in this bare-bones state, but she elaborates on most tracks with enough rock, pop, and even country elements that they never sound like exercises in nostalgia.

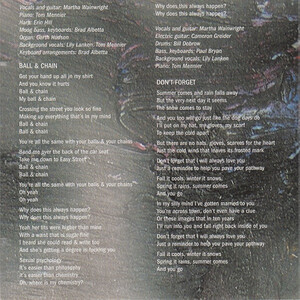

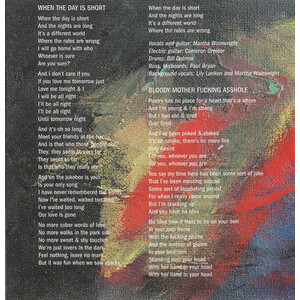

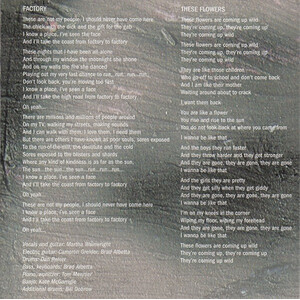

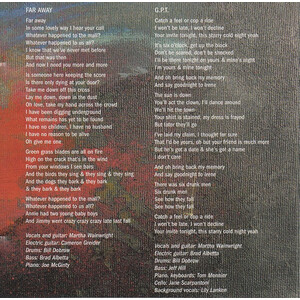

But it's her lyrics and vocals that are the focus of this debut. Martha doesn't write hooks so much as she inflects them with a versatile voice that moves fluidly from intimate exhalations ("Don't Forget") to angry exhortations ("Ball & Chain") to florid cascades of backing oohs and aahs ("Far Away"). The refrain of "Factory"-- "I'll take the coast from factory to factory"-- remains in your head not because of the words' inherent rhythms, but because Martha rushes the first two, draws out the long o in "coast," then rushes the last phrase as her voice rises excitably.

Lyrically, she has a penchant for sly wordplay and frank confession, addressing romantic masochism and what she calls "sexual psychology" in "Ball & Chain". But her forthrightness can be highly deceptive. On "TV Show", she sings, "So when you touch me there I'm scared you'll see/ Not the way that I don't love you/ But the way I don't love myself." Deciphering those double negatives couldn't be more difficult: On first listen, it sounds like she loves the song's subject, but hates herself, but that extra "don't" between the "I" and the "love you" muddies the meaning. It's all a question of syntax, yet that one extra word thoroughly complicates the song while directly, even intimately involving the listener in her drama.

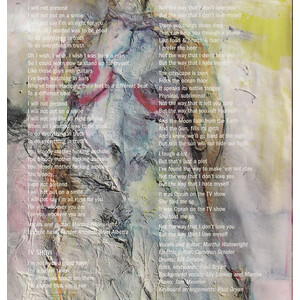

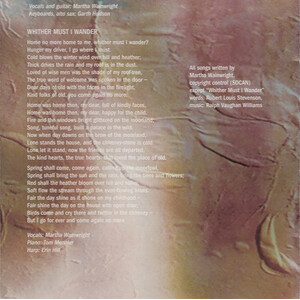

Of course, family plays a strong role on these songs. In addition to appearances by Kate (playing banjo on "Factory" and piano on "Don't Forget") and Rufus (singing on "The Maker"), she writes about their tumultuous family with a candor that would be more remarkable if it weren't a genetic trait. Martha's song about her father is called "Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole", and the pun of the title in no way detracts from the cathartic defiance of the lyrics: "I will not pretend/ I will not put on a smile/ I will not say I'm all right for you." Yet, despite the endless comparisons these family dramas provoke, Martha Wainwright proves Martha Wainwright has a strong, distinct, fully formed musical identity, which would be just as impressive by any other name.

-pitchfork

No Comments