Information/Write-up

THE VILETONES: DEATH TO THE DABBLERS

A True and Possibly False History of the Last Toronto Punk Band That Mattered

“They’re not making a statement. They know no-one listens unless it’s to call you a hypocrite. And besides, they aren't that pretentious.”

— Jeremy Gluck

In 1976, a kid named Steven Leckie walked onto a Toronto stage, cut himself open with glass, smeared his blood on the front row, and birthed the Viletones — possibly the most gloriously self-immolating act of punk rock's first wave.

He called himself Nazi Dog, not out of ideology, but as a deliberate affront — to audiences, to punk orthodoxy, and to the Toronto suburbs that raised him. The band’s shows weren’t concerts, they were exorcisms. “It’s like doing Apocalypse Now every night,” Leckie once said. “And I’m always Kurtz.”

Alongside bands like The Diodes and Teenage Head, the Viletones helped form the holy trinity of Toronto punk, but they were always the chaos wing — too violent for the mainstream, too pure for the poseurs. Leckie wasn’t singing about alienation. He was alienation.

“If I die when I’m 24, I don’t care. One thing I know is, I’m not going to live past 30.”

— Leckie, age 20, stitched up and covered in motor-oil blood

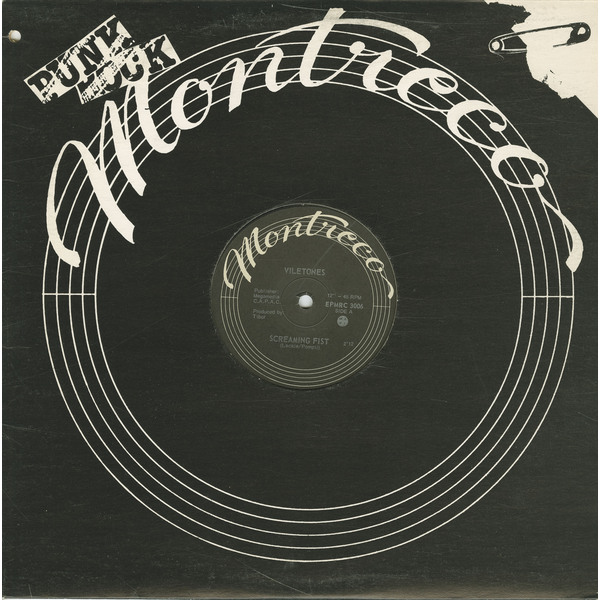

LOOK BACK IN ANGER, their first EP (1977), is still considered one of punk’s purest artifacts. Raw, brief, and terrifyingly alive. But unlike other punk bands who signed to majors and sanded off the edges, the Viletones refused to be tamed. Managers quit. Labels flinched. The band went further underground.

Leckie became infamous for his refusal to rehearse — or as one critic put it, “the only band that’s acquired any degree of international celebrity on the strength of their first EP and a handful of uncompromising performances in New York and England.” In a time of slogans and safety pins, Leckie was too real for fashion. He was Baudelaire with blood on his boots.

“They hear Trudeau say something smart and they get offended. He’s an intellectual, and they can’t handle it.”

— Leckie, crucifying Canadian culture

And then… he vanished.

PART 2: LONDON FOG, FLEURS DU MAL, AND THE ART OF BLEEDING

“The Viletones aren’t trying to prove anything to anyone. Or judging from the outside world — even themselves.”

— Toronto Star, 1994

Sometime in the early '80s, after scaring the shit out of Toronto, Leckie left. Where most punk casualties ended up on milk cartons, he turned into a ghost with a passport — living in London from '95 through '98, diving headfirst into the underground art world, “hanging out in the ruins with the painters,” and making art that bled like his lyrics once did.

Back home, he re-emerged under his birth name, Steven Leckie, and opened Fleurs du Mal on Queen Street East — part boutique, part museum of madness. Named after Baudelaire’s ode to beauty and rot, the shop was a crash site of glam, glitter, bones, vintage jackets, riot gear, dead poets, and righteous snarl. Every item was curated with the gravity of a blood pact. “We don’t cater to squares or seekers of mass-produced corporate clothing,” he told the Toronto Sun. No shit.

“What we’re doing here is glitter rock and punk — the two sexiest sides of the ’70s.”

— Leckie, now a fashion anti-retailer with a Nietzschean streak

Posters of Sid Vicious and handwritten slogans ("Clothes For Heroes") hung beside t-shirts from Vivienne Westwood’s SEX. The Barenaked Ladies weren’t allowed in. The Vatican got a copy of the catalog. Somewhere between punk rock, fashion installation, and dadaist fuck-you, Fleurs du Mal became the most important art project Toronto didn’t understand.

He also started painting — violently. Barbed wire halos. Charcoal wounds. Faces erased in layers. It was art that looked like it had survived a riot. (“You can’t take my art away,” he told the Star, “It’s like a war wound.”)

In 1999, he appeared — shirt open, cigarette in hand — at the Du Mal gallery, surrounded by paintings that looked like demon archives. A decade earlier, he was swinging chains onstage. Now he was exhibiting at group shows alongside Satanic puppetry, freak-show fashion, and post-porn children’s theatre.

“He’s always Kurtz.”

— Mary Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol, American Psycho), who cast Leckie in a role in American Psycho, calling him “the talented psycho we all seek in the heart of darkness.”

But art never replaced punk. Punk became art.

By the mid-’90s, The Viletones returned — not with nostalgia, but fury. Shows at the Opera House, Lee’s Palace, and across Europe followed. They weren’t legacy acts — they were still dangerous, and still better than most of the bands they inspired.

“They’re not that sophisticated, you see… That’s the difference with me. It’s Jean Cocteau, man — if they don’t get it, fuck ‘em.”

— Leckie on The Tragically Hip and the culture of Canadian mediocrity

He hated grunge (“It’s just heavy metal in thrift store clothes”), dismissed Nirvana’s sincerity as cowardice, and swatted away any mention of the industry like a fly:

“I don’t want your music paper. I don’t have a lawyer. I don’t do deals. I make art.”

He didn’t just reject fame. He crucified it.

PART 3: DEATH TO THE DABBLERS — A MANIFESTO IN BLOOD AND GLITTER

“Should I let them in? They look like dabblers.”

— Steven Leckie, glaring at kids in Adidas jackets

By the time the '90s swung around and the industry started rounding up “alternative” bands like they were cattle, the Viletones were sharpening their knives again. New bands were playing punk. But the Viletones had become punk — or whatever lay beyond it. They weren’t part of the genre. They were the genre’s warning label.

Leckie saw through the sheen:

“It’s all about youth, sex, and style — and a lot of musicians don’t bother to step out of the musical realm. But you can step into Rimbaud or Picasso.”

He did both.

He also threw up outside the Horseshoe Tavern and judged your haircut.

In interviews, Leckie routinely rejected the nostalgia industry, spat at lazy mythologizing, and warned against turning raw rebellion into a coffee table book. He quoted Cocteau, insulted The Tragically Hip, and blamed CanLit mediocrity on a national allergy to passion:

“They hear Trudeau say something poetic and they get offended — their meek-minded mentality won’t allow that. He’s a fucking intellectual and they can’t handle it.”

Where others were canonized, Leckie stayed in exile. No PR team. No merch empire. Just a living contradiction in eyeliner, making art, dodging rent, and still shattering himself for the stage.

When the Viletones returned to Lee’s Palace or the Opera House, the audiences didn’t come for the songs. They came for the ritual. Blood, chains, coats on fire. Songs like “Danger Boy” and “Screamin’ Fist” didn’t date — they mutated. Leckie’s voice, half snarl, half invocation, stayed feral.

“You can’t take my art away. It’s like a war wound.”

— Leckie, cradling a canvas like a weapon

A WORD ON THE NAME

Leckie took heat for the “Nazi Dog” moniker early on, but he always shrugged it off with venom or irony, depending on his mood.

“I ain’t no Nazi,” he once told The Star. “But I wanna be a dog. I like dogs. I used to own a dog until I became my own dog.”

Critics didn’t always get it. Journalists swarmed the stage; some wrote Leckie off as a provocateur. Others saw something more uncomfortable — an artist dragging trauma, violence, and beauty into the spotlight and refusing to clean it up for mass consumption.

Even Danny Fields (Ramones manager, punk tastemaker, godfather of outsider cool) wrote:

“If you want to talk about the power of music itself — not the band or its visual froth — in ‘swaying the mob’ toward a fascist or neo-fascist state of being — well, that’s another essay.”

Leckie never asked for that essay. He just kept bleeding for the next line.

EPILOGUE: A CULTURE THAT NEEDED THEM

“Some people must come out when the culture needs them. Some people must come out and moan and squawk and scream ‘Fist!’ — and not do anything about it. Knowing that if I don’t, then I am not fulfilling my role.”

— Steve Leckie, 1994

From high school dropout to transgressive icon, from blood onstage to barbed wire halos in gallery walls, Steven Leckie is the rare figure who refused to shrink for the sake of fame. He made no careerist pivots, no cleanup albums, no Vegas reunion acts. His band didn’t get sober — it got meaner.

And the Viletones?

They’re not an artifact. They’re not a reunion.

They are still unresolved.

“If I’m not nice, it’s because I’m not running for office.” — Leckie, 1999

He never did. But he rewrote the book on how to destroy the office before someone else tries to put your name on it.

-Robert Williston

Steven Leckie (aka Nazi Dog): vocals

Freddy Pompeii: guitar

Chris Paputts (aka Chris Hate): bass

Mike Anderson (aka Motor X): drums

Produced by Tibor

No Comments