Information/Write-up

Some years ago, during a think session at Calgary's Glenbow-Alberta Institute for an exhibit on Canadian country music, an older country musician defined "old time" music as "European." The exhibit, sadly, never happened, but the musician's comment, along with other moments of the session, have stuck with me. Sooner or later, someone will do a definitive study of the term, which can mean everything from African and Irish American banjo and fiddle duets of Kentucky to the melange of European, Prairie Canada, and Hollywood cowboy sounds offered by Calgary's CFCN Old Timers and other Prairie dance bands. If you haven't noticed, North America is in the midst of a polka revival, and the range of polka styles, from Slovenia to Scandinavia, is being explored and remixed, by such different performers as the traditionalist Canadian Polka King, Walter Ostanek, and the exploratory fringe rockers from Texas, Brave Combo.

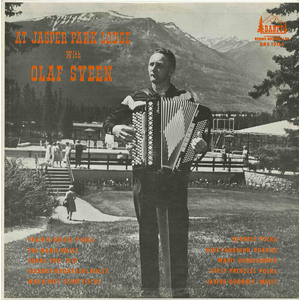

The polka may not need to be revived in western Canada, of course-it remains to be demonstrated that it ever died. A quick check at Calgary's Rideau Music failed to turn up any of Olaf Sveen's old time dance collections, but I learned that a Gaby Haas volume in stock was a new publication, which is a little surprising, since the Edmonton accordionist died in I987.

None of Sveen's recordings are currently available, either. He made over twenty-five of them. In I978, Ted Ferguson estimated that he'd sold I50,000 records. Not bad for someone who came to Canada "...with $I0 in cash and a $45 accordion...," and who was always a hardworking musician whose success never took him away from the core of a musician's career: teaching, banquets, weddings, &c. The lead of the Ferguson article features a description of Sveen's longterm gig at the Londonderry Hotel lounge. The article itself, like the following interview, stresses Sveen's joy in music.

-GWL

My birthday is April I8, I9I9.

We always had an accordion at home, you see. My grandfather, he actually was an American, a Yankee. He was born in Norway, but he went and stayed in Colorado for many years and became an American citizen. He got killed in the mine in Colorado in I935. He was the best player, better than my dad.

In the evening, my grandfather said, he'd go out in the park and play, and the people, especially the Italians, he said, would gather 'round. He was a rough player; he was hard on the accordion. But he was a very good dance player. My dad played the accordion, but he didn't take it very serious.

My grandparents on my father's side were married in I890, and they had hired an accordion player to come and play for the dance. He lived at Skei, about ten kilometers from 0yabakken, my grandfather's place, where I grew up later. When the wedding day came, the accordion player picked up his accordion and started to walk towards 0yabakken. We have to keep in mind that this was I890. As he was walking along, a horse and buggy caught up with him. It was the parson; his name was Nils Brandt, I believe, and he was on his way to marry the young couple. He offered the accordion player a lift, which he gladly accepted. The local historian Hans Hyldbakk wrote about this incident later, and it must have been quite a sensation when it happened over a hundred years ago, or else it would have been forgotten by now.

We still have an accordion at home, my brother has it; it's all fixed up, and it was a I9I3 accordion. The new ones work a little bit better, but not much. It's a button accordion, what you call a diatonic accordion: out and in, out and in, out and in Two rows. I graduated into chromatic, you see, during the 30s.

In Norway, before I left, I played music by Italian composers, German, lots of Swedish, probably more Swedish than Norwegian, and I had some awful good numbers there, you know, at that time, and it was popular, on record players, gramophones. I never was a jazz player, that kind of stuff, but I played international music, I'll say that much. I usually played solo, without a band.

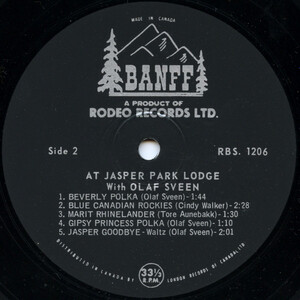

I went to the local players, and they gave me advice and showed me music. I learned from one guy named Tore Aunebakk. He's dead now, but he was a good player, and he was such a nice guy, and he wrote so much music for me, it's unbelievable. There's a local museum there now; I sent them some of his music.

I learned to read music in the 30s. I never learned much by ear. They say, "If you learn by ear, you must be musical," and I can't be musical: I'm not learning by ear. If you learn by ear, it's easy to find lots of mistakes in your playing. No matter how good you are, it's best not to learn by ear.

I didn't want to play for people. I didn't think I was good enough at first. It doesn't pay to be too hasty. The accordion is very difficult. I should know. Accordion, I read in an American music magazine, is the second hardest instrument in the world. Violin is number one. They say accordion is number two. There's so much happening at once, you see. The piano, that's difficult, too, but at least you don't have to pull the piano back and forth. And I've seen so many pianists that say, no, the accordion, nothing to it

My home was in Surnadal until I left, but I played all over Nordmore county. I was never home weekends. Most of my money came from playing. Especially I945-I played Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, every night! I still have a mark on the hand here from the straps, and I was very tired! Unbelievably tired, but if somebody phoned up, you gotta go. That was I945, and I've always been busy playing.

The end of the war! You can't believe how happy they were, even though they had nothing left, hardly. Well, young girls probably only had one change of clothes. But they were happy, and it came back slowly.

My brother at home, he was my student-one of my worst But then, it was one Sunday afternoon, I had been to some place playing, and I was sleeping, and I woke up. There was this dancing and accordion playing downstairs: little brother George playing, nine years old, full blast, like music you hear on the radio. He had been practicing behind my back! That would be during the war-he was born in I934, and he was 9 years old.

That was downstairs in my house, though. During the war, there was dancing up in cabins and stuff like that, far from the road. They finally put out a decree: No more dancing. We were supposed to think about the poor guys in the Eastern Front, who lay dying, and while we were dancing-it was a sacrilege.

But you can't stop it like that, and people would come and, you know, "We won't get caught! Come on, let's go!" And we'd play, over, down behind the bush, by the river there. Finally got caught there, had to pay a fine.

But I got the money back after the war. The Norwegians paid the money back. A policeman came on the stage, I was playing for a dance, and he says, "I have an envelope for you, that's to make up for the fines you paid in I943." It was only about twenty bucks or so, but the money I paid during the war because I got caught playing was better money than what I got paid after the war. I was glad to have the money back and get it off the books!

Can you imagine a young girl, just I7 years old in I942 or '43, all of a sudden there's no dancing, and gatherings were even frowned upon. And food was very little-mostly fish. And there wasn't much to live for. Some of them missed their young life, completely. Those are the years when the young girls want to dance, and the young boys, too!

I came to Canada in I949. The situation over at home was pretty lousy at that time. We had just had a Second World War. You couldn't imagine today, we came to the stores in Norway, and wanted to buy something, say syrup, you had no syrup over there. You couldn't buy syrup in the stores in I949. The next time you could get it, a couple of months from now, and they stood in line, waiting for syrup. After I was over here, it changed there.

I came to Canada to be a farmer. A Norwegian had a farm in Saskatchewan, we worked there first. Four of us came, two men and two girls. My brother Lars, he's still there. My sister Ingeborg, she's in Kamploops, B.C. And sister Maret she's still there.

I started to play for dances in Saskatchewan. Played for dances. Can't get away from it. Always somebody phoning up. And then I joined Eddie Mehler and his Southern Playboys. Eddie Mehler's still around; he just turned 65 now, in July. He's in Estevan, Saskatchewan.

Mehler is my wife's second cousin, something like that. He and Matt came to the farm in the Fall. It was chilly. Harvest was over. All of a sudden this car comes in the yard, and Ingeborg looks out and says, "Hey, there's three Indians in the yard!" They looked very brown and sunburned. They had heard about me and wanted me to play with them.

They were picking a name one night. "How about the Western Playboys?" No, that's too common, there's more bands called the Western Playboys. "How about Southern Playboys?" Southern Saskatchewan, Estevan, you see, is southern Saskatchewan. It doesn't make sense to have a name like that, but that's the name they used. We were only eight miles from the border.

What I played was mainly Old Time, and favorite numbers like "Missouri Waltz," stuff like that. That's very hard to play. I was getting influenced by the cowboy style now, a little bit, I didn't play real Old Time.

Western swing. I was never a Western player, either, but I ruined some of my Scandinavian style. I think it did in the beginning, playing with Eddie Mehler. I had to try and be like the rest of them, you see. I certainly was not a Western player when I first came in I950. I was not a Western player at all. Hank Williams, and stuff like that. I'd never heard of it.

Some songs, he was very good at them. One of his songs, "Lovesick Blues," where he goes [yodel]-l had the music, but it doesn't sound right on the accordion. It has to have vocal cords to sound right.

At that time the accordion was very popular in Saskatchewan. But, then, it died out: the Beatles, Presley, and all those gee-tars, you see. It's hard to find accordion music even in Norway now. I It's coming back. In popular music, they're using accordion, but they're not using it right! Sometimes they just make it appear that they play the left hand. But it's a good sign. Accordion is unique; it's the happiest music around, no doubt about that.

Eddie Mehler played lots of Hank Williams, and I taught him the songs. Because he didn't read music. He got so much music from the music companies down east, piles of it. "Lost Highway." That's the first one I ever taught Eddie, I950, maybe even late I949. None of those guys could read music.

When I came from Norway, I found some very careless accordion playing. Nobody could read notes. Barn dances. That's how it was. They learned tunes from recordings and didn't always listen too close. In Norway you didn't fool around with the melody because people knew them, you see. But there was some good musicians in Saskatchewan, too. In Regina there was some very good players.

And now there's many good musicians coming up. Have you heard about Kimberley? They have this festival at Kimberley, B.C., every year now for twenty years. I didn't go this year, for some reason, but I've been there very often. I've been a judge four times.

"The Blue Skirt Waltz" came out in those days. Frankie Yankovic. I met him several times. That was his biggest hit. I have the original recording of that. It's full of mistakes, if you listen close and have the music. But he gets away with it; nobody cared. He doesn't play it that way himself anymore, I think.

American polkas, they've got a different swing to them. They don't dance polkas the same way in Norway that they do here, you know. They come from Slovenia and Poland, and they have a different way of dancing it.

I think that every country has their own The difference between Norwegian and Swedish music! And Danish is not even music! They play accordion, but not like any Scandinavians, and I have tapes to prove It. But Swedes and Norwegians, they are much the same.

Finlanders are different again! Finlanders are fantastic, too. Fantastic players. Related to the Russians, must be. I like Russian accordion playing. I saw this guy pick up the accordion and play "Flight of the Bumblebee," his fingers go like lightning.

Everybody tries to have their own style. The Italian is nice, too. On Channel 43, the French station, every afternoon from I :30 to 2:00 is a program of light music, singing, and accordion playing. That accordion playing is not like anybody else's, either. They have very good players and don't play like any Scandinavians or Germans at all.

I tried to play Ukrainian music, but you've got to be born there. You've got to be born in Ukraine; well, you can be born in Canada to Ukrainian parents. But they have their own swing to it that's hard to copy. I think so. Lots of my students play Ukrainian music, and I play it, too, but I don't think I'm qualified to play Ukrainian music.

There's an old man, he's been coming here for years. He'll be 94 in September. He plays Ukrainian music, and he sings Ukrainian music. And most of the notes are wrong. And the bass is always the wrong bass. One doesn't worry about that. He finds some bass, and "Good enough!" And he plays, and he sings, it's unbelievable. That's real Ukrainian! But I don't think it'd get first prize if people had knowledge about notes.

Just this morning I had a student from India, from Madras. I said, "That's pretty good. You're coming from India, and you're playing a schottische!" And even the schottische is supposed to be a melody from Scotland. Well, now, it was in the beginning, but after a while, they get changed around, so that a schottische from Scotland is not the same a schottische from Scandinavia anymore. It's only the name. Even the Rheinlander, that's from Germany, and that changes, too, a Scandinavian Rheinlander, that's something different. But this guy from India, he's learned that schottische he played from me-he didn't learn it from the guys in India so it sounds like a Scandinavian schottische!

I bought my own farm, a small one. But you've got to have so much capital. If I'd been there twenty years earlier, there'd have been nothing to it. But they were into it big time. Hundred thousand dollars for a combine. And I wanted to play the accordion. But we didn't sell the farm. We sold it recently, and we have land in Alberta.

In Norway we didn't have to invest so much, and we could borrow a neighbor's machine. We did it by hand: cut the grass by hand. All they had was horse drawn machines, but lots of it was done by hand.

It's awful hard to start farming when you don't have any money, so I tried all I could to get out of it. I had to, since I had kids. A friend of mine got in touch with a music school in Edmonton, Roberts- Tait School of Music. It was located close to the Greenbriar Hotel. So we packed everything, had a I955 Monarch. This was I962, and we came to Edmonton, and I was in my right element because I was able to read music.

My first record was called "OIle's Waltz." It was a 78 rpm. I ended up with no copies, up until about two years ago. CBC Regina, Saskatchewan, they had a beautiful copy and they sent me a tape. This was recorded in the early 50s. Every recording could be a story because, well, it was hard to get the fellows to come into Regina to record it. Harvest time? It was past harvest time, but one guy would come back and say he had some hay bales laying in the slough, and it rained, and the next day it froze. And he couldn't get to the hay bales because of the recording. "Olle's Waltz"? I won't play that today. I've got a tape of it. You can't imagine how fast we played it in those days! Oh, gee! I can't play that fast anymore. There's no way! We were full of life at that time!

There was Al Reutsch, he had a company, Aragon, in Vancouver. And I guess it was because Eddie Mehler-I had played with him, but I was married now and I couldn't go with him to Montreal. And he went to Montreal, maybe I952 or '53, and made a record. I got married in I952 and lived for a while on a farm at Browning, Saskatchewan.

I said to myself, "If he can make a record, I can make a record." I had a dance band, and I wrote to Aragon, and I said I wanted to make a hundred copies. And I'd pay for it. And I sent the tape and the money, and all of a sudden here comes - it was November, snow, and in those days the roads weren't so hot. And I drove to the railroad station, and there was the package. Maybe four packages. I think it was one hundred copies.

The first man I met, a neighbor, I said, "You want to buy a record'!" And he said, "No." And I said to myself, "Here I have a hundred records, and I can't even sell one." That was a blow. They cost a dollar or something-I forget the price, but it wasn't much.

Then my banjo player, Joe Fieber, and the guitar players, we got together, and I gave them so many copies, split them up, and now to try to sell them. And the rush on them, it was not difficult selling those records.

I sent them to the radio stations. They were on every station. My sister-in-law said she heard the record played on seven different stations one day! So it was very popular.

But it wasn't done right. There should have been some business man behind that. You've got to have some publicity. How can you expect a record to sell? The people would come to the store and ask, "'Olle's Waltz'!' Never heard of it. What label is it on'!" "Aragon." "Never heard of it." I came to Weybum later, and I brought a copy. I went to the station. The guy said, "Do you have 'OIle's Waltz'?" "Yeah, I'm Olle myself." And he said, "I wish I had that a month ago." And then I made more. Accordion records, they were popular in those days. This is the early 50s, the middle 50s.

I made the tape in Regina. CKRM. I had phoned earlier and booked a studio at the station. But when we came to the studio and were getting ready to start playing, we got an order to be as quiet as mice, for the well known sportscaster Johnny Esaw was doing an interview with a bunch of Regina Roughriders football players in the next studio, and he was afraid some of our sinful sound could get on his tape. At last Esaw was finished, but by that time was so rattled-"stress" was not invented yet!-that I goofed up "OIle's Waltz" a couple of times before it was supposed to be good enough. But then the engineer said to us, "You guys can not afford to make any mistakes on the polka for the other side, or else you will have to come back some other day and finish it." We lived ca. I30 miles from Regina, so it was out of the question. So we started playing" Accordion Polka," and we finished it with two minutes to spare. I believe the interview with the Roughriders was forgotten a long time ago now, but only a couple of years ago, I found out that CBC Regina still had a 78 rpm recording of Olle's Waltz" and" Accordion Polka."

In those days, you know, you could get it for nine dollars, you could rent something. It wasn't a big amount. Small amounts. There was Bill Webb on guitar, and Albert Leptick, on guitar-there was two guitars. And Joe Fieber on banjo. Myself on accordion. I think that's it. Bass guitar. Bill Webb was a fantastic player. We got another batch of records, and then all of a sudden, Aragon was out of business, so I couldn't order any more records.

I made my first long play record in I955. Still a farmer, and I made records. That's how come I got here. The records got me to Edmonton. In Edmonton I got together with Gaby Haas.4 I was teaching and playing, and I was awful busy. Gaby Haas, he gave me the names and addresses. London Records. They had a warehouse here, and they came around, came to visit me in the house.

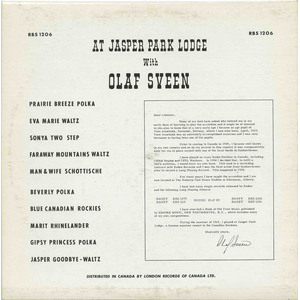

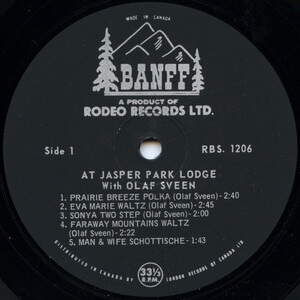

After Aragon Records went out of business, I recorded with-it probably was Point. No, Banff/Rodeo between '55 and '60. In Edmonton, with the Gaby Haas orchestra. Sometimes, I even made solo recordings. I already had a few records when I got to Edmonton. I don't know how many. I don't keep track of this. I made records for several years before I got here. Later on, I made two or three a year. Only with Aragon did I have to pay for it myself.

Banff/Rodeo headquarters were in Halifax! They were very far away, and that was not so good. I sold the most records with London Records. A salesman came around, and they had a warehouse. Point was only a branch of a bigger company, in Toronto. London Records was in Montreal.

My records sold mainly in the West. How do you expect a record made in Edmonton to sell in Newfoundland or Nova Scotia'? They have' accordion players there, too, but it's a different sounding accordion. I can't play like that; I don't even try.

I heard of someone who went up north, way up north. Baffin Island. And he stayed with the Eskimos. He had a phonograph, and he had Olaf Sveen records in the snowbanks. I think it's true.

It was pretty hectic for a while there, playing 5 or 6 nights a week at the restaurant. Gaby Haas had a restaurant - he had three restaurants. He played the good nights, Friday, Saturday, but I played earlier in the week, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. There weren't many people. Played for four hours. But you've got to do it. Somebody got to do it!

Gaby Haas died too young. It probably was much his own fault. He had headaches and he suffered headaches, you see, but he didn't want to take time off and go to the doctor. I went to see him at the end, and he said to me, "I can't stay in the hospital. I've got too much to do."

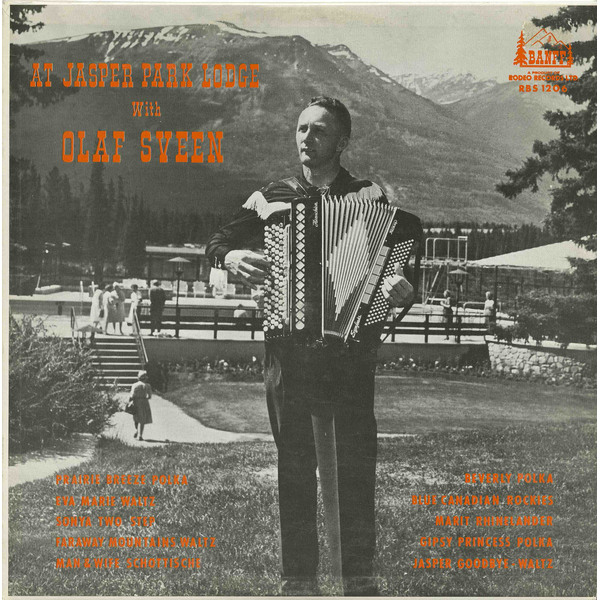

We lived in the Beverley district of Edmonton a couple of years, and then bought this house here. I worked at Jasper Park Lodge all summer, a couple of years, four months. I've been teaching ever since. I've tried to teach for a studio, but it doesn't work out. And my wife Eva is a cook. She was cooking in the kitchen and I was playing on the stage, for fifteen years in one hotel! And now I'm 75, and I'm supposed to be retired, but I'm not retired I00%.

I don't perform anymore. I'm still teaching. Now my students are so nice to me. It's easier. They know I'm old, so they're nice to me.

There's an accordion club here. A bunch of old guys. I'm one of the oldest! They lived their whole life doing something else, and now they take up the accordion. It's good for them, you know. I've been struggling with the accordion all my life! I never can understand those guys, driving a brand-new Cadillac, can talk about accordion. I never put them in the same category as me because I never had a car like that. But I played much more! That's all right, to have a hobby, very good.

I had a radio program on CKUA for three and a half years, I think it was. With Dr. Bourassa, of the Department of Psychology, and Dr. Tom Nelson, of the University of Alberta. It had a lot about the Viking times. Dr. Tom Nelson says that the Viking culture was way ahead of the other cultures of the times. He wasn't shy about it. He used to help me get books published. He wrote the introduction to this tune book. It's hard to sell Old Time music nowadays.

I wrote a book in Norwegian, mainly about accordion players. In Norway and here. The title is Nordmann i Canada, but it could have been called "accordion players I have met." It came out in Norway, and I was here. I tried to push it, but you can't do that. It wasn't looked after properly. I sold some copies here, sold some in the States. [ don't know how many copies of the books sold. [ wasn't there to oversee it.

It's much easier for me to say it in Norwegian. Some little stories. There was a story about a man who was dancing and all of a sudden he fell. He gets up, and he's mad, and he says to the orchestra, "You guys," he says, "look how you play!" Sometimes those kind of jokes go over bigger in their original language, you see. You can put mild swear words in there, make it entertaining.

I write to a paper called Driva in Sunndal, close to where I lived. In I974 I was home for the first time after 25 years. I talked to guys who said, "Have you heard about Driva?" And I talked to my high school teacher, and the principal, and they all said I should write. Write to Driva. And my Dad said, "Olaf," he said, "just playing is not enough. You got to write." My Dad said that. So I've been writing to Driva ever since. And other little papers I write to in Norway, Accordion News. Twenty years I've been writing to Driva, and I get the paper sent air mail. I write about the accordion and many other things.

The Accordion News in Norway, they have an awful time getting enough stuff for it. Nobody wants to write. They want to read the paper; nobody wants to write anything. They have all kinds of accordion clubs, but the editor wrote to me and said, "Please write because we hardly get anything to print." Usually they send in something really dry - they had a get together, so many people there. And nobody wants to read that.

I joined the union when I played at Jasper Park Lodge in 1963. I didn't need to be in it when I played in Saskatchewan, not in the farmlands. It's only a couple of years since I cancelled it because 1 don't play now anymore. I don't have any regrets that I didn't play enough. If you play in places for fifteen years…..

It wasn’t always that great. Sometimes it’s a lousy crowd. Sometimes it's fun, but not always. I played enough. My fingers on the right hand don't move like they used to. The doctors-I think it's because I played too much, but you can't tell the doctors, they think it's something else, a nerve, something to do with a nerve. I know that at the end I had to force myself to make certain chords. I don't have any regrets that I didn't play enough, my only regret is that maybe I played too much!

-Olaf Sveen

No Comments