Information/Write-up

They have been called “pioneers” and “as quintessentially Canadian as Medicare and street hockey.” Their first album has been hailed as one of the best Canadian releases in history. And you probably haven’t heard of them. The band is Simply Saucer, and by rights, they should have been lost forever, buried in the gritty depths of Hamilton’s music history. Formed on the fringes of the scene, Simply Saucer garnered no critical praise until a decade after they broke up. This is their story, a story as anomalous as their sound.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, mainstream music had become relatively friendly. Yet on the outer planets, rock ’n’ roll seethed, mutating into new, edgier forms. The Warhol-inspired aesthetic of the Velvet Underground, the raw power of the Stooges and the psychedelic space rock of early Pink Floyd thrilled critics and inspired other musicians. At the same time, they could not compete with radio’s more accessible sounds.

These were the types of artists that inspired Simply Saucer. Yet if Lou Reed couldn’t reach a wider audience in New York, what chance did Simply Saucer have in Hamilton? Ahead of their time, Simply Saucer would have to wait for time to catch up – which would take over 20 years.

Simply Saucer was helmed by Edgar Breau, whose sojourn into the fringes of modern music began early. He began with country, Elvis, the Beatles; when he learned to play guitar in his youth, he picked away at songs by Gordon Lightfoot and, later, The Kinks’ Ray Davies. As he grew up, he soaked himself in British psychedelia from Pink Floyd to the Soft Machine. He dipped a toe in the Pacific with Moby Grape and the Grateful Dead. He revelled in the disjointed genius of Captain Beefheart and the hypnotic racket of German bands like Can and Amon Düül. Record geeks in London and New York could just hit their respective Sohos to find these albums. In the Hammer, however, such music could only be had via special order. These special orders were stock in trade at Bob Moody’s Record Bar on John Street North, where Breau loitered and made friends with other local rock intelligentsia.

“We used to get together and have record spinoffs,” Breau recalls. “We’d get a bottle of wine and rate records on originality and all kinds of categories. We had fun like that.” Inspired by the rock counterculture, as well as authors such as Kerouac and Wolfe, Breau and a friend headed west in 1972. They thumbed down highways and panhandled for change; Breau returned to Hamilton in the fall, a changed young man. “There was a creek at King and Quigley,” he recalls. “I tossed all the books in the creek and that was it for schooling. I went right into putting this band together.”

From various corners of the Record Bar, Breau gathered people to help him release the sounds that circled in his head. It began with friend Paul Callili and, one by one, other likeminded musicians came on board – Dave Byers, Kevin Christoff, Neil DeMerchant, Breau’s foster brother John LaPlante.

In an upstairs apartment not far from Moody’s, this unlikely sextet set about making a racket that most Hamiltonians would never understand. LaPlante adopted the mysterious moniker Ping Romany; he twisted knobs on oscillators and early synthesizers, creating spacey sounds inspired by Hawkwind, Sun Ra and Karlheinz Stockhausen. The band maintained the Velvets’ cool, the Stooges’ power and Floyd’s sonic expanse. They also maintained their distance from Hamilton’s other bands, who were happy playing cover tunes in local bars. “We were pretty hostile towards what was going on in town,” Breau says. “Full of piss and vinegar and almost contentious. Hamilton wasn’t exactly a thriving artistic mecca in the ’70s.”

The refusenik attitude landed the band no gigs, but for a time, that was fine. They were content, rather, to turn up the feedback, leave the apartment and see how far away they could hear the noise (as it turned out, James Street). The lack of forward motion, however, eventually tired some members. Callili departed for college, Byers simply departed and the rest of the band relocated to a grungy storefront rehearsal space over at 220 1/2 Kenilworth Avenue North.

Though they had never played a show, word of Simply Saucer reached the ears of Rick Bissell, a transplanted Montrealer, who offered to manage the band. He booked their first unlikely performance – in the basement of St. Alban’s Anglican Church.

“It was east end neighbourhood kids that came out to see us,” says Breau. Those east end kids, however, were not prepared for DeMerchant’s violin (which he really couldn’t play), Breau’s cacophonous audio generators or the performance of an hour-long piece aptly entitled “Noise.” Fights broke out. The authorities were involved. A defining statement was made.

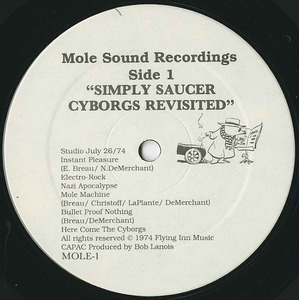

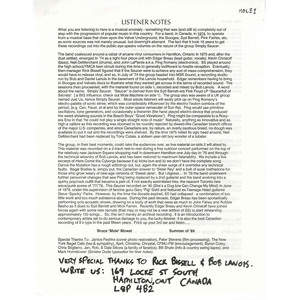

Despite the dubious nature of their first public performance, Bissell was able to book more gigs for Saucer, often at unsuspecting high schools from Elmira to Hawksbury. He also suggested the band record a demo tape, so Saucer went into the Master Sound Recording Studio, run by producer brothers Bob and Dan Lanois. The resulting tracks included the band’s mathematical space jams (“Mole Machine”), snarling proto-punk (“Nazi Apocalypse”) and Velvety nihilism (“Treat Me Like Dirt”). The demos were stellar – but Canadian record labels remained unconvinced. Saucer continued to make New York sounds in their Hamilton home without attracting the attention they deserved.

Meanwhile, Breau made his home in “The Office” on Kenilworth, a place he describes as “dumpy” and not fit for permanent habitation. The neighbourhood was rough; members of the Parkdale Gang would hammer on Breau’s back door in the wee hours. The band played where they could. One infamous performance took place on the roof of Jackson Square on June 28, 1975 – coincidentally, on the same day Pink Floyd played Ivor Wynne Stadium. Still, it wasn’t enough for Bissell, who believed the band could be moulded into something more marketable. He drew up a management contract that gave himself the right to make certain decisions on the band’s behalf. Breau declined, and their business relationship with Bissell came to an end.

Breau was still intent on making the Saucer fly, but keeping the group together became a challenge. He began to write more direct, succinct songs, which left little room for LaPlante’s trademark twiddling; eventually, Ping left the band. Drummers rotated through the lineup. When someone stole their instruments, the members of Saucer were even more discouraged, despite being insured; in late 1976, Saucer disbanded briefly, but Breau quickly revived the group. They returned as a three-piece, living and rehearsing in a rented house on Ferguson Avenue.

Thus began the so-called “third phase” of Simply Saucer. Toronto’s Queen Street West had become a burgeoning scene for the punk movement. Breau met an American fanzine publisher named Gary “Pig” Gold who, after coming to see them practice on Ferguson, saw a connection between Saucer’s new sound (influenced by artists like Television and Patti Smith) and the Queen West scene. Before long, Gold booked the band to play in Toronto and became their unofficial manager.

While it lasted, it was a wild ride. Gold released the group’s first record – a 7” of two new songs, “She’s a Dog” and “I Can Change My Mind.” The single, now very much a rarity, met with modest success. This year marks the 30th anniversary of its release. Yet despite this success, the band – Breau, Christoff, drummer Don Cramer and guitarist Steve “Sparky” Parks – had trouble keeping priorities in lines. Associates in and around the Saucer circle had dabbled in drugs, and now, in need of income, some of them moved into “product distribution.”

“In the end there were really scary people coming down,” Breau recalls. “I’d be downstairs rehearsing and there’d be guys that came along that scared me just to look at them.” Meanwhile, the Queen scene began to fray and the shows dried up. Parks left the band. Christoff followed. Breau watched in disappointment as his dream dissolved. As the band collapsed, there came a final nail in the coffin. Someone had an affair with someone else’s girlfriend. Discoveries were made, items were smashed, blood flowed, drug use exploded, and eventually, Christoff found one of the parties dead in the house from a self-inflicted shotgun wound. “That sealed the whole thing in a very negative way,” Breau says.

It was the proverbial end of an era. Breau married, had children and drifted through the 1980s. He found jobs here and there, studied cabinetmaking, and became interested in philosophies that were directly at odds with his previous life in the rock counterculture. He embraced his religious roots by reading Aquinas and delving into conservative, pre-Vatican II Catholicism. He read G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, interested in the ideals of the distributists. He traded his electric guitar for an acoustic, and began writing music that owed more to folk and country than rock ’n’ roll. He wilfully turned his back on Simply Saucer. What he didn’t know was that the band was far from over.

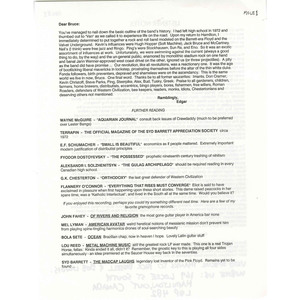

Ironically, it was Breau himself who unwittingly brought Saucer back to life. It was Breau who mentioned the group’s existence to local scenester Bruce “The Mole” Mowat, and Breau who procured the fabled demo tapes from Bissell for Mowat to hear. Mowat was floored. Over the years, Saucer’s influences had edged their way above ground to some extent. Stadium-filling groups such as REM and U2 cited Television and the Velvet Underground as influences, while the Cowboy Junkies had an enormous hit with the Velvets’ “Sweet Jane.” That Simply Saucer had not released an album was a wrong Mowat wanted to right.

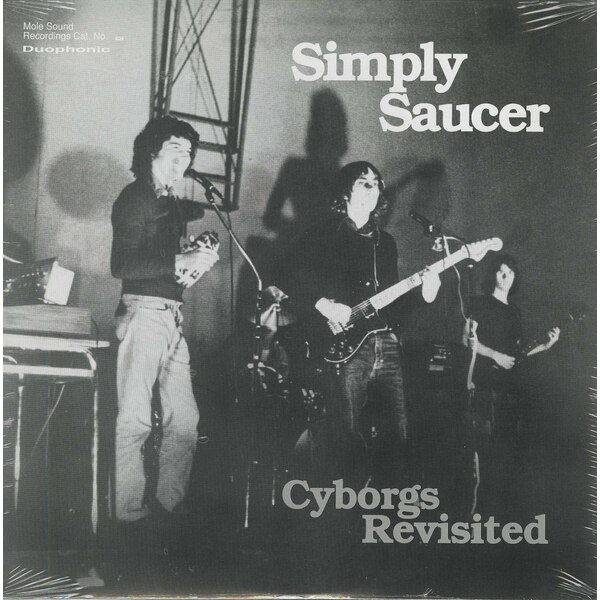

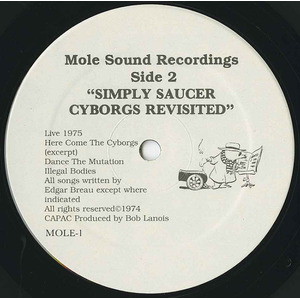

Loans were made, tapes were mastered and vinyl was pressed. Dubbed Cyborgs Revisited, the album consisted of two separate recordings. Side One featured the Lanois demos. Side Two featured the rooftop Jackson Square concert. Less than a thousand copies were made, but the album’s impression was deep. Musicians such as Julian Cope and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore converted. Critical acclaim was immediate. Some reporters called it the Greatest Canadian Album Ever.

Obviously, it pained Breau to discover something he had intentionally forsaken was now considered worthwhile. Instead of using the new interest as a springboard for his solo career, he went in the other direction and stopped playing live entirely. Breau retreated further into isolation with his family, even home-schooling his children. Meanwhile, outside, someone invented something called the Internet. Interest in Cyborgs Revisited grew exponentially, even as copies of it became impossible to find.

It was then, in 2002, that Hamilton’s Sonic Unyon Recording Company approached Mowat about putting together a better CD release – with extra bonus material, extended liner notes and proper distribution. Breau, who was slowly beginning to re-emerge with his acoustic guitar, agreed to the re-release and began performing again, albeit as Edgar Breau, not Simply Saucer.

Sonic Unyon’s re-release was an enormous success. It is likely to be Sonic Unyon’s biggest seller this decade. Most recently, Cyborgs Revisited appeared in a book entitled The Top 100 Canadian Albums, where it landed at #36 – above albums by The Band, Neil Young, Shania Twain and Rush. “All of a sudden the band started getting a kind of mainstream exposure,” Breau says. “Not just the people who read the book, but the artists. Maybe the Barenaked Ladies or Blue Rodeo heard it.”

Today, Breau has re-embraced his past repertoire. Knowing the only context he could play them in was Simply Saucer meant that, after years of avoidance and varying levels of denial, Breau had to revive the group as a living entity. It was not a decision he took lightly. “I had to try to picture myself singing those songs – and those words,” he laughs. “How am I going to feel? ‘Here Come the Cyborgs?’ I mean… come on.”

Yet Hamilton, once grey and discouraging, had come to prize their prodigal Saucer sons. It was a Hamilton label that resurrected the band on CD, and local fans flocked to the first performances by the group in almost 20 years. Along with stalwart Kevin Christoff, Breau is surrounded by younger Hamilton musicians Dan Wintermans (electronics), Joe Csontos (drums) and Steve Foster (guitar). The scene they once sneered at has changed. Saucer are no longer outsiders, even if their music remains on the fringes.

Since their reformation, Simply Saucer have even recorded a new album, which many believed would never occur. Entitled Half Human/Half Live, it mirrors the studio/live split of Cyborgs Revisited, and consists mainly of material Breau wrote in the ’70s. “It’s a transitional record, from the old to the new,” says Breau. “I’d like to eventually broaden the fan base. In doing that you might lose some of the critical acclaim, but the band’s capable of more than just playing punk and psych.”

As such, Breau already has plans for the next album – new material, freshly written, and likely different than the music for which Saucer has (finally) become known. Some would say it’s a fool’s errand; that Breau shouldn’t mess with Saucer’s critical success. Yet what is Saucer’s story, if not a series of new beginnings?

Breau plans on titling this future album Nothing is Ever Lost. To him, it is a reference to Faulkner’s The Reivers, but to fans of Simply Saucer, it has a deeper meaning. Simply Saucer’s music could have been – perhaps, in some ways, should have been – lost. They were, as Mowat says, “something that was… completely out of step with the progression of popular music in this country,” and as such, they fell through the cracks. Fate and circumstance pried up the floorboards, and what was underneath was a gem so rare it demanded we retrieve it. It was not forgotten. It was too important. HM

-James Tennant

Let's say you're skeptical when you flip through the liner notes and read quote after quote, all from reputable rock publications, praising Cyborgs Revisited as nothing less than "the greatest Canadian rock album ever." And sure, they overreacted, but you understand, because this is everything a cult album should be: the only trace of a lost band that was so exciting, but so obscure it's a wonder there's anything to remember them by at all.

This album first came out in 1989, a full decade after Simply Saucer had broken up. Flipping through the small booklet, you can read countless anecdotes of rock band purgatory: gigs that almost sparked riots, others that did nothing at all, rough demos, stolen gear, and of course, continuous line-up changes. In spite of it all, the band kept experimenting-- like the time they cranked up the feedback in their Hamilton, Ontario rehearsal space, and went outside to see if they could hear it (they could), locking themselves out in the process. The local firemen who had to let the band back inside described it as "the loudest sound heard in these parts since World War II."

Here's a band that could splice the DNA of Syd Barrett and Soft Machine with Iggy Pop and the Velvet Underground, that could bridge post-psychedelic mind-altering electronics with a buzzed proto-punk urgency: the ultimate garage band, rehearsing constantly and trying everything and doing it all at top fucking volume. And right after they finally got around to issuing their debut release, a well-received seven-inch, in 1978, the band split and became history.

The saga, however, was just getting underway. Longtime Saucer fan Bruce "Mole" Mowat uncovered enough of the band's material in the late 1980s to assemble an actual posthumous full-length album. A one-single cult band that could have been consigned to Nuggets III: Original Artyfacts from the Northern Territories and Beyond instead captured their own spotlight. Mowat culled nine songs from a forgotten studio session and a free afternoon show at a shopping center, and crazily, they're all so fantastic that you can properly call them a legacy.

The studio cuts come from a 1974 session recorded by Bob Lanois in his and brother Daniel's basement studio (the live set was recorded a year later). We'll never know what the band's original epic setpieces sounded like, but apparently, by this point, frontman and main songwriter Edgar Breau was cutting the material down into more concise songs (if jarring and very eccentric ones)-- it's all the fury of the band's live sprawl crammed into the most condensed possible space. These sessions are explosive, with Breau playing the space-rock guitar hero while Ping Romany works out on Moog synth and some other analog electronics. The three live tracks, meanwhile, see the band stretching out: drums and bass gallop through on "Illegal Bodies", setting up a noisy busy-circuit solo from Romany that sets the stage for Breau's most precise, shrieking guitar attack. Even at a free show on a Saturday afternoon you can tell these guys were an absolutely crushing entity in the flesh.

But jams and noise-rock don't always ossify well onto vinyl. Which brings us back to the songs: a whole set of garage rock classics that are both ecstatic and bluntly riff-bound. Breau wrote lyrics that were strikingly direct-- from "Instant Pleasure"'s demand for carnal reward, to "Nazi Apocalypse"'s crass punk humor, to "Bullet Proof Nothing", which just keeps demanding, "Treat me like dirt." And though Breau's voice, while strong and clear, has no actual remarkable qualities (I'm saying he'd never stand out in a garage-rocker line-up), it's the perfect counterbalance to the music, grounding Simply Saucer's instrumental flights and Romany's "third ear" electronics.

Sonic Unyon's reissue collects the 1989 album, and also tacks on a half hour of rehearsal and live tapes. The later material (dating from '77 and '78) has the band arcing away from psychedelia and closer to proto-punk; Ping Romany has quit and Steve Parks has joined the band on second guitar. The bonus tracks sound rough but they include some gems, like the bluesy "Low Profile" demo or the album's only ballad, the affecting "Yes I Do". Sonic Unyon also included the first CD issue of the band's single, "I Can Change My Mind", along with its flipside, "She's a Dog". The single deservedly made waves in its day, landing them a touring slot with Pere Ubu, but the band sounds diminished on it: the songs are jagged, semi-chaotic shards of sneer-punk with lyrics that snarl but that never hinge off the groin like the band's earlier work.

It shouldn't have ended there-- the band were slated to record an official full-length before they disbanded-- though it is hard to imagine how this band could have improved on Cyborgs Revisited; "I Can Change My Mind" and "She's a Dog", in particular, seem like formal grade school portraits after all the candid craziness that came before them. With all their ideas and influences it's unbelievable that we could catch them at a point of such balance, but that might have been because they didn't freeze up to perfect it. Simply Saucer made their defining statement without even knowing it. How can you beat that?

-Chris Dahlen; August 18, 2003, Pitchfork

No Comments