Information/Write-up

The last time I saw Joni Mitchell perform was a year and a half ago at Boston's Symphony Hall, in one of her final appearances before she forswore the concert circuit for good. Fragile, giggly and shy, she had the most obvious case of nerves I have ever seen in a professional singer. Her ringing soprano cracked with stage fright and her frightened eyes refused to make contact with the audience. It wasn't until well into the second half of the concert that she settled down and began to enjoy herself; even then it seemed clear that she would have preferred a much smaller audience perhaps a cat by a fireside.

Joni Mitchell's singing, her songwriting, her whole presence give off a feeling of vulnerability that one seldom encounters even in the most arty reaches of the music business. In "For Free," her one song about songwriting, she declared that she sang "for fortune and those velvet curtain calls." But she long ago renounced the curtain calls; and her songs, like James Taylor's, are only incidentally commercial: Her primary purpose is to create something meaningful out of the random moments of pain and pleasure in her life.

In the course of Joni's career, her singing style has remained the same but her basically autobiographical approach to lyrics has grown increasingly explicit. The curious mixture of realism and romance that characterized Joni Mitchell and Clouds (with their sort of "instant traditional" style, so reminiscent of Childe ballads) gradually gave way to the more contemporary pop music modern language of Ladies of the Canyon. Gone now was the occasionally excessive feyness of "Rows and rows of angel hair/And ice cream castles in the air"; in their place was an album that contained six very unromanticized accounts of troubled encounters with men.

Like Ladies, Blue is loaded with specific references to the recent past; it is less picturesque and old-fashioned sounding than Joni's first two albums. It is also the most focused album: Blue is not only a mood and a kind of music, it is also Joni's name for her paramour. The fact that half the songs on the album are about him give it a unity which Ladies lacked. In fact, they are the chief source of strength of this very powerful album.

Several of the lesser cuts on Blue give every indication of having sat in Joni's trunk for some time. The folkie melody of "Little Green" recalls "I Don't Know Where I Stand" from her second album. The pretty, "poetic" lyric is dressed up in such cryptic references that it passeth all understanding. "The Last Time I Saw Richard" is a memoir of Joni's "dark cafe days," cluttered with insignificant detail and reminiscent of the least memorable autobiographical songs on Ladies. "River" is an extended mea culpa that reeks of self-pity ("I'm so hard to handle/I'm so selfish and so sad/Now I've lost the best baby/That I ever had"). Joni's ponderous piano accompaniment verges on a parody of Laura Nyro, especially the melodramatic intro, which is "Jingle Bells" in a minor key. The best of this lot is "My Old Man," a lovely, conventional ballad.

These songs have little or nothing to do with the main theme of the album; developed in the remaining songs, which is the chronicle of Joni, a free lance romantic, searching for a permanent love. She announces this theme in the first line of the first cut, "All I Want": "I am on a lonely road and I am traveling/Looking for something to set me free."

The lonely road has taken her through a series of places in the past–from Chelsea to Sisotowbell Lane, from Laurel Canyon to Woodstock–and she had followed it in pursuit of the settled, long term happiness that has always eluded her. "All I Want" is a manifesto for that happiness; Joni has found a new lover and she bombards him with a list of her desires, piling them up in a quick succession of rhymes:

I want to talk to you, I want to shampoo you

I want to renew you again and again

Applause, applause–life is our cause

When I think of your kisses, my mind see-saws

The accompaniment–James Taylor and Joni strumming a nervous, Latin-flavored guitar part over a bass heartbeat that throbs throughout the song–perfectly expresses Joni's excitement and anticipation. So does the melody, a dipping, soaring affair which she sings in her sweetest soprano.

"All I Want," though it begins the album, marks the end of the long holiday journey described in "Carey" and "California." Both songs have the syncopated, Latin touch that characterizes the best cuts on the album. "Carey," a calypso about dalliance on Crete, had a definite festival flavor, but with a twist at the end: "The wind is in from Africa/Last night I couldn't sleep/Oh, you know it sure is hard to leave here but it's really not my home."

"California" jumps along in short bursts, the lyrics giving snapshots of Joni's European itinerary. Then comes the flowing chorus with its hint of tango, its plaintive pedal steel guitar and its homesick refrain: "Oh, it gets so lonely/When you're walking and the streets are full of strangers." The song is a model of subtle production; James Taylor's twitchy guitar and Russ Kunkel's superb, barely detectable high-hat and bass-pedal work give it just the right amount of propulsion.

In "This Flight Tonight," "A Case of You," and "Blue," Joni comes to terms with the reality that loneliness is not simply the result of prolonged traveling; the basic problem is that her lover will not give her all she wants. In "This Flight Tonight," Joni has walked out on her man, is flying West on a jet, and now regrets the decision. The lyrics, a clumsy attempt at stream of consciousness, are virtually unsingable and Joni's lyric soprano is hopelessly at odds with the rock and roll tune. But the chorus has just the wispiest trace of Bo Diddley and it sticks with you:

Oh Starbright, starbright

You've got the lovin' that I like, all right

Turn this crazy bird around

I shouldn't have got on this flight tonight.

In "A Case of You," James repeats the same dotted guitar riff he played in "California," only the melody here is slow, stately and almost hymnlike. The song is neatly divided in its ambivalence: each verse is about a setback to the affair, followed by a chorus in which Joni affirms: "But you are in my blood like holy wine." In comparing love to communion, Joni defines explicitly the underlying theme of Blue: for her love has become a religious quest, and surrendering to loneliness a sin.

It is only a short step from that to Joni's vow that she will walk through hell-fire to follow her man: "Well everybody's saying/That hell's the hippest way to go/Well I don't think so/But I'm gonna look around it though/Blue I love you." This is "Blue," the last cut on the first side but clearly the album's final statement, the bottom of the slope downward from the euphoria of "All I Want." For all its personal revelation, "All I Want" still sounds like a beautiful pop tune; "Blue," on the other hand, has the secret, ineffably sad feeling of a Billie Holliday song. Joy, after all, can be shared with everybody, but intense pain leads to withdrawal and isolation.

"Blue" is a distillation of pain and is therefore the most private of Joni's private songs. She wrote it for nobody but herself and her lover:

Blue here is a shell for you

Inside you'll hear a sigh

A foggy lullaby

There is your song from me.

The beauty of the mysterious and unresolved melody and the expressiveness of the vocal make this song accessible to a general audience. But "Blue," more than any of the other songs, shows Joni to be twice vulnerable: not only is she in pain as a private person, but her calling as an artist commands her to express her despair musically and reveal to an audience of record-buyers:

And yet, despite the title song. Blue is overall the freest, brightest, most cheerfully rhythmic album Joni has yet released. But the change in mood does not mean that Joni's commitment to her own very personal naturalistic style has diminished. More than ever, Joni risks using details that might be construed as trivial in order to paint a vivid self portrait. She refuses to mask her real face behind imagery, as her fellow autobiographers James Taylor and Cat Stevens sometimes do.

In portraying herself so starkly, she has risked the ridiculous to achieve the sublime. The results though are seldom ridiculous; on Blue she has matched her popular music skills with the purity and honesty of what was once called folk music and through the blend she has given us some of the most beautiful moments in recent popular music.

-Timothy Crouse

Commercial success didn’t sit easy with Joni Mitchell. Clouds had gone gold and brought with it a level of popular appeal that took away some of her everyday liberties. Having finished Ladies Of The Canyon in 1970, she vowed to take a year off, ostensibly to recharge her jaded batteries, but also to escape what she felt was an increasing sense of claustrophobia. “I was being isolated, starting to feel like a bird in a gilded cage,” she explained to Rolling Stone’s Larry LeBlanc. “A certain amount of success cuts you off in a lot of ways. You can’t move freely. I like to live, be on the streets, to be in a crowd…”

In many ways, it signalled the start of Mitchell’s conflicted relationship between art and celebrity. Now that the “black limousine” and “velvet curtain calls” of “For Free” had narrowed into the reality of her own life, she needed to regain her peripheral vision, restore a degree of clarity. Mitchell came to despise show business, declaring fame “a series of misunderstandings surrounding a name”. Not for nothing did David Geffen once tell her: “You’re the only star I ever met that wanted to be ordinary.”

There were major upheavals in Mitchell’s private life, too. Her intense love affair with Graham Nash, which had coincided with an accelerated spurt of productivity from both parties, was nearing its end, resulting in a series of petty squabbles. Against this backdrop, Mitchell decided to head for Europe, where she travelled around Greece, Spain and France. Her main seat of exile was the island of Crete, where she took up residence in a cave amid a hippy community in the fishing village of Matala. It was from here that she sent Nash a telegraph home. He was busy laying a new floor in Mitchell’s kitchen when it landed, it read: “If you hold sand too tightly in your hand, it will run through your fingers. Love, Joan.” “I knew at that point it was truly over between us,” Nash recalled, disconsolately, in his memoir, Wild Tales.

Mitchell was introduced to the Appalachian dulcimer on Crete and adjusted to the unhurried rhythm of local life. The experience brought her into contact with a number of characters, who in turn helped reignite her creativity. One such figure was Cary Raditz, a wild-haired American chef who was blessed, in Mitchell’s words, with “fierce-looking blue eyes” and “the mark of Cain on his brow”. The pair began a relationship, sealed by a song she’d written in honour of his birthday: “Carey”.

As more musical ideas started to flow, Mitchell noticed the formation of certain recurring themes – love, loss, escape, a quest for some kind of indefinable spiritual truth. And for all the delicious scenery, food and ready company, she was homesick. Shifting from one continental base to another only amplified the feeling. While in Paris, she poured her longing for her adopted West Coast into another fresh tune, “California”.

She returned to her native Canada in late July, playing Toronto’s Mariposa Folk Festival alongside James Taylor. Mitchell and Taylor had met a year earlier, at the Newport Folk Festival, but now they became romantically involved. A month or so later, she visited him on the set of his Hollywood road movie, Two-Lane Blacktop, where they wrote together and, as Taylor told Uncut in 2015, “had some of the most outrageous good times”. By October, they were sharing a stage at London’s Paris Theatre, recorded for BBC Radio One’s In Concert series, with Mitchell unveiling a handful of new compositions.

She returned to London at the end of November to perform at the Royal Festival Hall, where the new songs were met with unanimous approval by reviewers, among them the NME and Melody Maker. The latter’s readership was similarly smitten with Mitchell, voting her 1970’s Top Female Performer in its year-end poll (ahead of Aretha Franklin, Grace Slick, Sandy Denny and the recently departed Janis Joplin), despite her paucity of live shows.

Back home by early ’71, Mitchell and Taylor were viewed by the American music press as Hollywood’s golden couple; two young, photogenic singer-songwriters whose liaison embodied the free-spirited ambience of Laurel Canyon. Both set about preparing their respective solo albums, with Mitchell singing backing vocals on what would become Mud Slide Slim And The Blue Horizon – most notably on his cover of Carole King’s “You’ve Got A Friend” – and Taylor repaying the compliment by adding guitar to “California”, “All I Want” and “A Case Of You”. They also accepted an invitation from King to appear on a reworked version of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” for Tapestry, then being cut in the same A&M studio that Mitchell had booked.

The relationship quickly turned sour, however. Apparently devastated by Taylor’s decision to call it off, Mitchell funnelled her pain into the other songs she was recording for the appositely named Blue. The album duly became a document of a life in flux, a diary of physical and emotional displacement set against a backdrop of restless travel and doomed love affairs.

Short of the affectations of Clouds or the airy folk-pop of Ladies Of The Canyon, Blue was almost uncomfortably direct. Mitchell again refused to coat the songs in fussy arrangements, preferring to place her voice front and centre over spare guitar, dulcimer and piano, her vulnerability plain for all to hear. She later told Rolling Stone that “at that period of my life, I had no personal defences. I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes. I felt like I had absolutely no secrets from the world, and I couldn’t pretend in my life to be strong. Or to be happy. But the advantage of it in the music was that there were no defences there either.”

She was to use a more curious, semi-grotesque analogy in 2014’s Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words, telling interviewer Malka Marom that she’d dreamed she was watching “a bit fat women’s tuba band. Women with big horns and rolled-down nylon in house dresses, playing tuba and big horn music, and I was a plastic bag with all my organs exposed, sobbing on an auditorium chair at that time. That’s how I felt. Like my guts were on the outside. I wrote Blue in that condition.”

The implication here is that Blue is an unwavering litany of distress and despair, an inventory of misfortune with no light relief. But it’s actually a counterweight of ecstasy and agony, of the best and worst of times. Nash is supposedly the subject of the piano-led “My Old Man”, Mitchell riding the climatic extremes of romantic love in breathy soprano. “He’s my sunshine in the morning/He’s my fireworks at the end of the day/He’s the warmest chord I ever heard” she sings at her sunniest, her voice adopting the shifting cadences of jazz. It’s in direct contrast to the clouds that descend in his absence: “But when he’s gone/Me and them lonesome blues collide/The bed’s too big/The frying pan’s too wide.”

The exquisite “A Case Of You”, also rumoured to be about Nash, finds her trying to absorb the lessons of a failed love affair that refuses to let her move on. As if to measure the depth of its impact, Mitchell addresses her quandary in religious terms: “Oh, you’re in my blood like holy wine/You taste so bitter and so sweet.” The sensitivity of her lyrics is echoed in the deft accompaniment of Taylor’s acoustic guitar and in the poignant tones of Mitchell’s dulcimer, the latter providing much of Blue’s graceful fragility. As testament to its enduring pull, “A Case Of You” became one of her most-covered tunes, siring versions from as far afield as KD Lang, Nancy Wilson, James Blake, The Decemberists’ Colin Meloy and Prince (as, naturally, “A Case Of U”).

Of the trio of songs considered to be inspired by Taylor, “All I Want” alludes to the jalousies and insecurities that appear to have undermined their relationship from an early stage. All Mitchell wants, she sings, her fluted voice rising and dipping over silvery dulcimer, “is to bring out the best in me and in you too”. But it feels like honest delusion rather than realistic hope. Her opening lines give a truer indication of her emotional condition: “I am on a lonely road and I am travelling/Travelling, travelling, travelling/Looking for something what can it be/Oh I hate you some, I hate you some, I love you some.”

As she explained to Cameron Crowe some years later: “In the state that I was at in my enquiry about life and direction and relationships, I perceived a lot of hate in my heart… I perceived my inability to love at that point. And it horrified me some.”

The title track follows a similar line of confession. A sombre lullaby that finds Mitchell alone at the piano, the song appears to directly address Taylor’s heroin addiction – “Ink on a pin/Underneath the skin/An empty space to fill in” – while attempting to strike a note of optimism. Yet the prospect of self-destruction is too enticing to ignore out of hand: “Everybody’s saying that hell’s the hippest way to go/Well I don’t think so/But I’m gonna take a look around it though.” Arguably the most affecting moment on the entire album occurs halfway through “Blue”, when Mitchell sings “lots of laughs” with such forlorn resignation that it’s almost impossible not to well up.

Stephen Stills is on board for the more sprightly “Carey”, bringing a quasi-calypso rhythm to a tune that details Mitchell’s sojourn in Matala. Despite revolving around her activities with Raditz – another devilishly “mean old Daddy” to whom she’s helplessly drawn – it’s essentially a conflicted piece of travelogue that contrasts the simple hedonism of Cretan nightlife with homesickness for California. Mitchell can’t seem to decide what she wants more – the wine, laughter and scratchy rock ‘n’ roll of the Mermaid Café or the comforts of the Canyon. “Oh, you know it sure is hard to leave here Carey/But it’s really not my home,” she declares, double-tracking herself on harmonies, with Russ Kunkel adding tactful percussion. “My fingernails are filthy, I got bleach tar on my feet/And I miss my clean white linen and my fancy French cologne.” Raditz also features in the equally fidgety “California”, in which Mitchell’s loneliness and dislocation are all too apparent.

For all its thwarted romance and soul-stripping, it’s this question that sits at the heart of Blue. Mitchell is ultimately trying to reconcile her life with her art, compressing an elusive search for personal contentment into a grand artistic statement. Blue is sad, funny, poetic, revelatory and often achingly candid. And such an intensive experience that it feels much longer than it’s relatively slight 35 minutes.

Issued in the summer of 1971, Blue did brisk business both at home and abroad, cracking the Billboard Top 20 and peaking in the UK Top 3. It quickly became a landmark against which the work of all confessional singer-songwriters would be measured. Graham Nash says he still has a hard time listening to it. Mitchell herself has called it a turning point in her career.

It was also the album that finally established the 27-year-old as an American superstar. A situation that would once again test her ambivalence towards her own fame.

-Rob Hughes

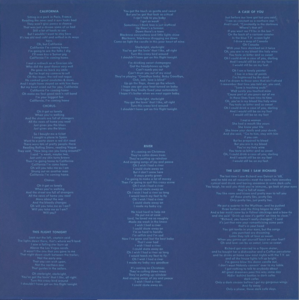

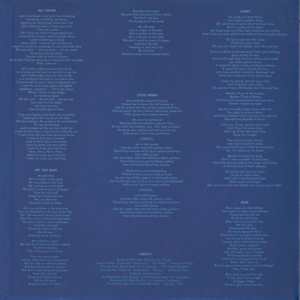

Stephen Stills: Bass & Guitar on "Carey."

James Taylor: Guitar on "California," "All I Want," "A Case of You."

Sneeky Pete: Pedal Steel on "California," "This Flight Tonight."

Russ Kunkel: Drums on "California," "Carey," "A Case of You."

Engineer: Henry Lewy

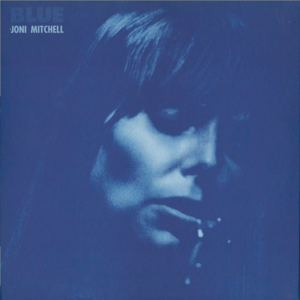

Art Direction: Gary Burden

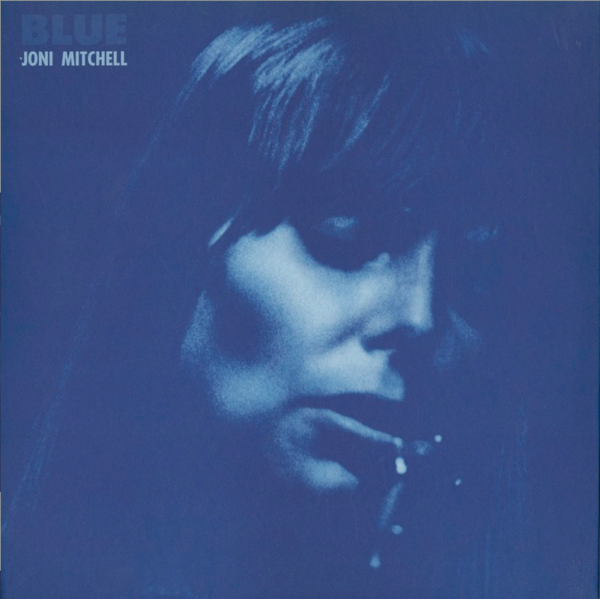

Cover Photography: Tim Considine

Recorded at A&M Studios, Los Angeles, California

All Selections copyright 1971, Joni Mitchell Music, Inc. (BMI)

Except "Little Green," copyright 1967 Siquomb Music (BMI)

No Comments