Information/Write-up

Omar Blondahl's Contribution to the Newfoundland Folksong Canon

Neil Rosenberg

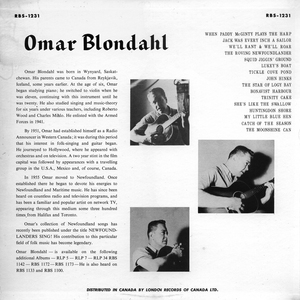

In the fall of 1955 Omar Blondahl, a thirty-two-year-old radio announcer and professional folksinger, arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland. Born of Icelandic parents in Saskatchewan, he was heading to Iceland to visit his father's grave. In Newfoundland, Canada's newest and easternmost province, he decided to stop and work for a while. Choosing local radio station VOCM on the basis of its odd call letters, he applied for a job. When he told the station manager that in addition to his skills as an announcer he played guitar and sang country and folk music, the manager excused himself, stepped out of the studio and came back from his office with a copy of the newly published third edition of the Gerald S. Doyle songbook.

Blondahl recalls: He tossed a Gerald S. Doyle songbook on the table and he said, "Can you sing any of that?" And this was my first introduction to Newfoundland folk music, so I opened it and thumbed through, I said "My God this is beautiful stuff." I had never heard any of it before and I said "This must be on all kinds of records," I said "I've never run across any of it." He said, "I don't think any of them are on records" and I thought this is a gold mine, you know, oh my.

It, along with the other published collections of Newfoundland vernacular song to which he had access, was a gold mine. Within hours he was singing from the book in his first broadcast. Ultimately he recorded nearly 50 of the 76 songs in Doyle's third edition, and between 1955 and 1964 he also collected other Newfoundland folksongs, composed locally popular songs about life in Newfoundland, and published a Newfoundland songbook. Today most Newfoundlanders over the age of thirty recall his name and identify him as the first person they heard sing Newfoundland folksongs on radio, television, or records. While Doyle and others had worked for years before Blondahl to familiarize Newfoundlanders with a body of song they believed represented Newfoundland's culture and tradition, it was Blondahl who finally consolidated and promulgated this canon to the province and the country.

Blondahl was the first full-time professional performer to specialize in Newfoundland folksongs, and the single individual most responsible for introducing the guitar as the accompanying instrument for folksongs in Newfoundland. He was also a distinctive character still remembered for his appearance and behavior, a local celebrity. Recently a St. John's woman who was in her teens and part of the "crowd" Blondahi socialized with told me that he was the first "bohemian" or "hippy" she'd ever met.

In 1955 Newfoundland was in the midst of its first decade as a province of Canada. Wartime prosperity and confederation with Canada had brought a higher standard of living to Britain's oldest colony, and middle-class suburbs were growing in St. John's and the handful of other cities in Newfoundland. The agenda of Joseph R. SmalLwood, the architect of confederation and Newfoundland's first provincial premier from 1949 to 1972, stressed progress and modernization. Electricity was being extended to the most isolated communities, and on this very large island, roughly the size of Cuba, which had never before had more than a few hundred miles of road, where local gazeteers gave distances between communities based on sea routes measured in nautical miles, new roads were being built. In another decade they would link the province's widely scattered communities in a highway network.

"Progress and modernization" are not necessarily antithetical to folk culture but often this is the perception and such was certainly the case in Newfoundland during the fifties. Yet Newfoundlanders had recognized and celebrated their folk heritage in many ways during the previous half century. Smallwood himself had built his reputation as a broadcaster by promoting a positive national self-image through the use of folklore.4 And even as he was pushing Newfoundland into a new role, other members of Newfoundland's cultural elite were constructing a nostalgic literary image of the pre-Confederation fishing village, the outport, as the site of Newfoundland's traditional culture and the wellsprings of national character.

Folksong was an integral part of this image from its beginnings. Since the turn of the century St. John's publishers and writers had been selling songs and recitations of Newfoundland's past to Newfoundlanders. St. John's pharmaceuticals distributor Gerald S. Doyle partook of the widely-held feelings of patriotic nostalgia which local songs evoked, and had published his first songbook, distributed free, in 1927. By the time of Confederation in 1949 this influential businessman's widely distributed second edition of 1940 had furnished the song played on the carillon bell towers in Ottawa when Newfoundland officially joined Canada in 1949, A.R. Scammell's "The Squid Jiggin' Ground."

By 1955 the Canadian folk music establishment had added Newfoundland's folksong traditions to the national canon, giving them a prominent place in publications like Fowke and Johnston's Folk Songs of Canada, in broadcasts on the government's national CBC network by Edith Fowke and Alan Mills, and in records by Mills, Ed McCurdy, and others. The National Museum had sent fieldworkers to document the song traditions of Newfoundland's outports, and the first vintage of Kenneth Peacock's work from several such trips could be found both in Fowke and Johnston and in the third edition of Doyle given to Omar Blondahl.

But in Newfoundland the connection between what were locally thought of as "Newfoundland songs" and the still-new popular interest in folksongs and folksingers, represented by the activities of Fowke, Mills, and others based in Toronto and Montreal, had not reached a large public.7 That connection was made by Blondahl.

Like many children of immigrants, Omar Blondahl, who grew up in Winnipeg, did not start speaking English until he began school. By the time he reached high school he had studied piano, violin, voice, and music theory, and had performed in local Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. By his late teens he was working in radio dramas. In 1943, following several years of Army service, he returned to radio, working for the next eight years at radio stations in western Canada as a dj, announcer, and performer. As a performer he was involved in drama and music. He played some fiddle but mainly rhythm guitar in old-time music orchestras and sang folksongs to his own guitar accompaniment as a soloist.

In 1947 he joined the staff of CFRN in Edmonton, Alberta. During his years in Edmonton he also appeared on CBC shows with the bands of old-time fiddler Ameen "King" Ganam and polka accordionist Gaby Haas.8 Following a successful stint in organizing a radio March of Dimes campaign at CFRN that drew the largest contributions in Canada for 1951, he took the advice of well-wishers and went off to seek his fortune in Hollywood. Following two interesting but not particularly productive years, during which he made his first commercial recordings, he ended up in Portland, Oregon. There he joined Smiling Ernie Lindell and his New England Barn Dance Jamboree. For the next two years he toured with this band as fiddler and solo vocalist with, in his words, "a ballad singing act."

Late in 1955 he left that band and, deciding to visit Iceland, he got a job on a boat and came to Newfoundland, where he stopped to work for a while in order to earn the rest of his passage. It was then that he embarked on his career as a professional folksinger specializing in Newfoundland folksongs, described at the start of this paper.

As a singer of folksongs, Blondahl consciously patterned himself on Burl Ives. One former employer told me: "He even walked like Ives."10 ASt. John's man recalls a joke about Blondahi: "They used to say that Burl Ives was trying to be Omar Blondahl."11 Like Ives, who took his radio moniker of "The Wayfaring Stranger" from a song in his repertoire, Blondahi called himself "Sagebrush Sam," borrowing from the cowboy song "Tying Knots in the Devil's Tail" to come up with an alter ego which reflected his western background. He resembled Ives in other ways. He played small guitars like those used by Ives, using a quiet plucking technique which utilized neither plectrum nor fingerpicks. His vocal delivery, in a tenor voice, was understated and light, though "trained." This mode of performance, which only worked in a small-group setting, in a silent concert hail, or in conjunction with a microphone, was, for its time, an innovative commercial metafolksong style. In effect it was an artistic representation of the widely held idea that authentic folksongs were delivered in an impersonal non-dramatic way. Charles Seeger, reviewing records by Ives, Richard Dyer-Bennett, and Josh White in 1949 and discussing the "almost classic simplicity of folk art," observed that: the vanguard of contemporary fine-art composition has come to prize certain factors in music above all others the strong, bare, almost hard, melodic line, the austere harmonic and contrapuntal fabric, the steady tempo, the avoidance of a sentimental dramatization of detail, in short, emphasis upon the very qualities that most distinguish the broad traditions of American folk song.

The popularity of groups like the Weavers and the Kingston Trio who initiated the great boom of the early 1960s has overshadowed the popularity of Burl Ives in the preceding decades. In the late 1940s and early 1950s his was the name, face, and sound that generally came to mind when "folksong" was mentioned. His autobiography, written in the mid-forties, portrays a role model that appealed to young men of that era. He describes modest hinterland origins, a stint at college, and years of rambling, a common enough narrative for men who came to adulthood in the depression, during which he performed folksongs learned first at home and later from diverse sources. He believed they were more meaningful than the jazz and pop songs many audiences demanded of him, and he persevered in singing them even when it meant lost jobs or being run out of town for singing such smut as "Foggy Foggy Dew." Aware of far left folksong activities, he articulated liberal Democratic values, but was for the most part not involved in protest song; rather he valued folksong because it was simple but meaningful art that had stood the test of time. Through his carefully crafted narrative runs a theme of romantic conquest; as he rambles and sings, sensitive women, recognizing his artistic validity, love him while the philistines reject him for his non-commercial obsession, later regretting it when he achieves success.

This image of the lovable wandering macho minstrel had its visual dimensions as well. In an era when respectable middle-class men were clean-shaven and short-haired and worked in shirt, tie, and jacket, Ives was bearded, had what passed at the time for long hair, and dressed casually. The look was "bohemian," associated with the genteel iconoclasm of the artists of the day.

With this image came a musical repertoire that mixed songs of old and new world origins to create a nationalistic historical canon, a record of American history and its roots in British culture. Emphasis was upon songs of personal experience, and upon the various dramatic dimensions they conveyed, from humor to tragedy. The rambler image was bolstered by this repertoire; politics were encountered only in the safe-haven of the past. Among his popular favorites were many with Irish connections, and a considerable number of chanties and related sea songs.

Omar Blondahl was only one of many younger men who followed Ives' model not only in image, style, and repertoire but also in an occupational pattern that combined radio, drama, and public concerts. When he arrived in Newfoundland these patterns were already well established in his life. His folksong repertoire included, in addition to a considerable number of Ives' songs, several of his own from western Canada: Robert Gard's "The Ballad of the Frank Slide," about an Alberta town destroyed by a landslide in 1903, and "The Lost Lemon Mine," an Alberta prospecting saga.

In the Gerald S. Doyle song-book he encountered a repertoire entirely new to him which resembled that of Ives: set in the romantic nationalistic historical past of Newfoundland, it had strong Irish connections and a preponderance of nautical topics. Although Ed McCurdy and Alan Mills had preceded him in performing Doyle songs in a style resembling Ives' (though more in the concert baritone mode), Blondahl's easy synthesis of Doyle's folksong repertoire and Ives' folksinger style was far more extensive than theirs.

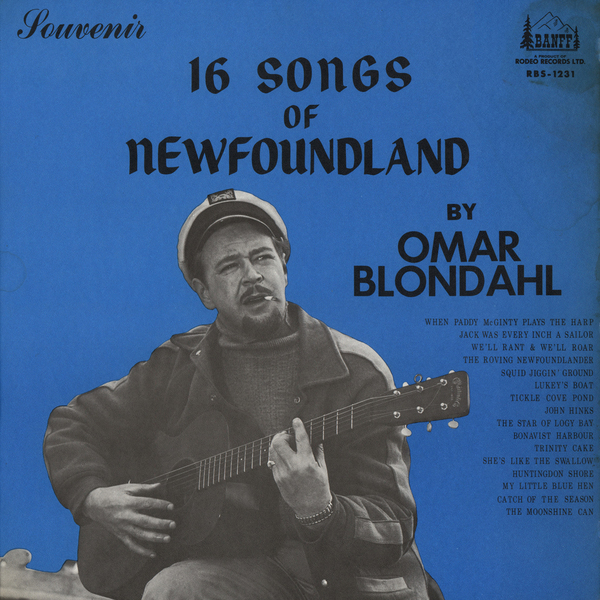

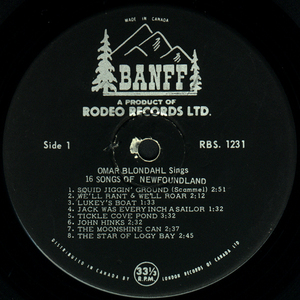

He quickly became a popular radio personality in St. John's, and within months of his first broadcast had made his first album for Rodeo, a new Montreal-based company that was scouring the Atlantic provinces for popular radio performers to be recorded and locally marketed: fiddlers, accordionists, and vocalists of many styles. On it were eleven songs from the new edition of Doyle, including the best known ones from earlier editions and phonograph recordings like "Squid Jigging Ground," "We'll Rant and We'll Roar," "Lukey's Boat," "I'se the B'y," and "AGreat Big Sea Hove in Long Beach." The title song of the record was an arrangement of Masefield's "Trade Winds." If some of the songs were already well-known, others were new and seem to have been helped to popularity by Blondahl's recordings, including "Feller from Fortune," "Harbour le Cou" (later issued on a single), and "The Old Polina", the latter being issued on a 78 rpm single along with "Squid Jigging Ground" at about the same time as the album was released.

It was so successful that Rodeo released a second album just three months later. Already Omar's experience as a local broadcaster and performer showed in the songs included, for although all but one could be found in the latest Doyle songster, three reflected his interaction with listeners who'd furnished him with new songs and variant texts: "Kitchey Coo" was a version of a song which appeared in Doyle as "Bill Wiseman", and which apparently came to Doyle from Peacock. Blondahl described it as "another traditional song with arrangement and special words by Omar Blondahl," adding that "this is one of many Newfoundland songs which may be found in several versions." "Hard, Hard Times" had likewise been collected by Peacock in several versions, one of which he had given to Doyle; Blondahi had sung the Doyle version on the radio and received a letter containing several additional verses from a man who told him his father had composed the song. Omar felt the melody "lacked the lilt that [he] thought it should contain" and so rewrote it. This has become the standard melody and text of the song, still widely known and performed in Newfoundland today. Its satirical social protest theme makes it a key text for Newfoundland singers and audiences. The "Moonshine Can," the only song on Blondahl's second album which was not in Doyle, was a song composed on the Island's relatively remote northern Peninsula; it is the complaint of a man convicted and fined for his illegal still after a neighbor informed upon him. It too became a local key text and is still popular today for affirming the idea that there is nothing wrong with "a drop of moonshine," and much wrong with an informer who rends the social fabric. Listeners sent Blondahl versions of this local song which he collated to create a province-wide favorite.

Also within his first year or two in Newfoundland Rodeo released several 78 rpm singles for juke box or radio play. One paired the favorite composition of St. John's broadside composer Johnny Burke, "The Kelligrews Soiree," with "The Wild Colonial Boy." Blondahl included popular local accordionist Wilf Doyle (who was also appearing on VOCM) on the recording, making it the first example on commercial record of the accordion-guitar synthesis which would, by the end of the sixties, emerge in the sound of Harry Hibbs as the local commercial country sound, today epitomized by Simani.

Another single paired "Concerning Charlie Horse" and "The Return of Charlie Horse," two songs about a party involving the retrieval and burial of Charlie, the horse who fell through the ice of Angle Pond in Mahers near St. John's in the spring of 1956. "Concerning Charlie Horse," which Blondahl co-authored along with a local man, who along with Blondahl was one of ten named in the song, was a hit in St. John's and is a good example of a moniker song which achieved popularity in part because listeners could identify the names and nicknames of the men in it.

A third significant single was commissioned and paid for by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company, locally known as the A.N.D. Company, owners of a large paper mill in Central Newfoundland. On one side was Omar's newly composed "The Business of Making the Paper," a step-by-step description, with much technical language, of the process whereby logs move from forest to pulp to paper. It was written so that each verse could be matched to a full-page cartoon ad depicting the processes and including Omar in every panel. The company ran this as part of a Christmas promotion which included sending copies of the record to customers. On the flip side was Omar's rendition of "The Badger Drive," a song praising the company management composed by John V. Devine, who'd been fired by the company and wrote it in a successful bid to regain his job. This song had appeared in every edition of Doyle and is Newfoundland's best-known local lumberwoods ballad, even though it is atypical of the genre in almost every respect.

Omar's third album of Newfoundland material, "A Visit to Newfoundland," was tourist-oriented. The photographs on the cover and back included colorful and distinctive sights, fishing villages, old St. John's, and examples of distinctively dressed local people. Canadian National Railways provided all of the photos, as well as the notes, which consisted of several paragraphs about the pleasures of" a different kind of vacation" on "comfortable steamers" with "scenery you will never forget" and "a hardy, hospitable and friendly people who have preserved their individuality for hundreds of years." All of the songs, about which the notes said nothing came from the Doyle songster.

Around 1959 Blondahl was enticed away from VOCM to CJON, a local radio and television station owned by one of Smallwood's proteges, Don Jamieson (later a cabinet minister in Trudeau's government). CJON had noticed their afternoon ratings were dropping when Omar came on, so they made him an offer he couldn't refuse, which included three 15-minute television shows a week.

His fourth album followed a trip to the ice on a vessel chartered by CJON sponsor, Bowrings, for Newfoundland's famous seal hunt. Film highlights of the hunt, including footage of him singing for the sealers, were broadcast over CJON. The seal hunt was then an industry on the verge of dying, but still thought of in nostalgic terms by Newfoundlanders. The great international protest movement against the hunt would not begin until the end of the decade. "The Great Seal Hunt of Newfoundland" included, in addition to songs from Doyle and other published and oral sources, three poems which Blondahl had composed about events during his trip to the ice.

CJON-TV exploited his connection with Newfoundland traditions in another way, by utilizing him, along with what the producer called "folk shots" much like those used in his CNR tourist album in a series of 25-second commercials for Bennett Breweries, the first instance of a now widely-followed local advertising practice of using folklore to promote the idea of beer drinking as a "Newfoundland tradition."

In the early 1960s two further albums of Newfoundland songs (during these years he also recorded albums of non-Newfoundland folksongs) repeated favorites like "Hard Hard Times," and introduced more Doyle songs as well as ones from other local song collections, his own collections, and his new compositions.24 Early in 1964 his final local commercial venture appeared: Newfoundlanders Sing! This songbook, compiled by Blondahl in St. John's, published by Robin Hood Flour Mills as a promotional venture; it included Omar's "Robin Hood Song," composed specially for the book. In addition to the 76 songs, many of which came from Doyle and other sources for his recorded repertoire, there was a "Foreword" by Oliver L. Vardy, Director of Tourist Development for the Province of Newfoundland, affirming the importance of folksong in the province's culture and commending Blondahl for his efforts at preservation.

The Newfoundland that Omar Blondahl encountered was in the midst of the most revolutionary changes in its history. During this period of rapid economic assimilation with Canada, many Newfoundlanders viewed the province's past and its traditions somewhat negatively. Even though the vote for confederation had been a close one, World War Two and the cold war years had brought an influx of American and Canadian servicemen and with them came prosperity which prompted many Newloundlanders to go along with the assimilative changes that were taking place now. Smallwood's attempts to bring in industry, resettle fishing communities, and reduce the importance of the fishery were generally accepted as the price to be paid for prosperity. And even though one of the foreign experts he brought in unscrupulously defrauded the Province, most outsiders coming to work in Newfoundland were welcomed, provided they demonstrated a sincere interest in the province.

Omar's business associations, which grew out of his work in lending his image to radio and television ads, led in other directions. He furnished musical entertainment for candidates in several political campaigns, for example. Gerald S. Doyle and the other songbook publishers of St. John's and elsewhere on the island had used their books for advertising both their own and other people's products. But Omar was a popular personality who was marketing both himself and his music. If folksong was impersonal, Omar was not.

This is the context in which Blondahl, who was in Newfoundland from 1955 to 1964, operated. He was an outside professional who brought new higher standards to his business. He utilized published collections, collected from his audience, re-wrote, collated, co-composed, and composed songs to construct a popular repertoire for a mass media context which his listeners in Newfoundland recognized and embraced as representing their culture, past and present. He met with success not only because he was a charismatic entertainer but also because he performed in the latest fashionable style, and because in doing so he synthesized musical elements previously separate, by being, for example, the first to mix the instrumental and vocal traditions on record by using an accordion with a song, and in a more general way by using a guitar to accompany songs that previously had either been sung unaccompanied or had been set to piano backing.

He also conveyed a sense of a unitary Newfoundland folksong tradition. Prior to Confederation Newfoundland was a nation in itself, and people were used to thinking of regions within it as having distinctive characteristics and traditions. Now the pressure of assimilation with Canada was forcing Newfoundlanders to think defensively and assertively of themselves as part of a distinctive regional provincial culture in which local differences were not as important as similarities which contrasted with the rest of Canada. Blondahl not only represented Newfoundland's folksongs to Newfoundlanders, he also represented them to the rest of Canada, through his records and via personal appearances on the mainland at such events as the first Mariposa Folk Festival, held in Ontario in 1961. By performing all of the Newfoundland songs he knew in a similar style Blondahl homogenized their sound and, without trying, made the point that Newfoundland folksongs are of a piece. At that time in the history of the province, no local individual could have done this. Yet it would happen soon enough and in radical ways not expected when Blondahl left 1964. Who could have imagined that by 1968 a St. John's rock band called Lukey's Boat would be putting a beat to some of the old songs that Blondahl had recorded?

-Memorial University of Newfoundland

St. John's, Newfoundland

Notes

1. Omar Blondahi, interviewed by Neil V. Rosenberg, Vancouver, May 28, 1988. MUNFLA 88-084, C11109.

2. Philip V. Bohiman defines canon with respect to folk music in the following way: "those repertoires and forms of musical behavior constantly shaped by a community to express its cultural particularity and the characteristics that distinguish it as a social entity." The Study of Folk Music in the Modern World (Bloomington: IN UP, 1988): 104.

3. [name restricted], interviewed by Neil V. Rosenberg, St. John's, Sept. 11, 1990.

4. Peter Narvaez, "Joseph R. Smaliwood, The Barrelman: The Broadcaster as Folklorist," Canadian Folklore canadien 5 (1983): 60-78.

5. See James Overton, "A Newfoundland Culture?" Journal of Canadian Studies 23(1988):5-22.

6. See Neil V. Rosenberg, "Folksong In Newfoundland: A Research History." In Ballades et chansonsfolkloriques ("Actes de la 18e session de la Commission pour l'étude de Ia poesie de traditional orale [Kommission fur Volksdichtung] de Ia S.I.E.F. [Societe internationale d'ethnologie et de folklore])," ed. Conrad Laforte. Québec: CELAT, Université Laval, 1989, 45-52; and "The Gerald S. Doyle Songsters and the Politics of Newfoundland Folksong," Canadian Folklore canadien, in press.

7. For a discussion of the native category of "Newfoundland songs" see George Casey, Neil V. Rosenberg, and Wilfred Wareham, "Repertoire Categorization and Performer-Audience Relationships," Ethnomusicology 16(1 972):398-99.

8.Omar Blondahl, letter to author, 12/29/90.

9. Blondahl interview.

10. Colin Jamieson, interviewed by Neil V. Rosenberg, St. John's, October 1, 1990.

11. Conversation with Kevin Noble, October 5, 1990.

12. Charles Seeger, "Reviews," Journal of American Folklore 62 (1949): 69.

13. According to Edith Fowke, "The Foggy Dew" was banned by CBC during the 1950s. For a variant text, references and a brief discussion, see "The Bugaboo" in Alton C. Morris, Folksongs of Florida (New York: Folklorica, 1981; rpt. of 1950 edition): 160.

14. Burl Ives, Wayfiring Stranger (London: Boardman, 1952).

15. Blondahl told me that these two were issued on "maverick labels in Michigan and California." "The Ballad of the Frank Slide" appeared on two later Canadian albums of his Rodeo RBS 1172, Omar's Favorite Folk Songs and Arc A-567, Favourite Folk Songs. It was composed by writer and folklorist Robert Gard, who spent several years during the 1940s in Alberta where he organized a collecting project. His Johnny Chinook (London: Longmans, 1945 [reprinted in 1967 by Hurtig in Edmonton and Tuttle in Vermonti includes chapters on both the mine (16-25) and the slide (174-180).

16. Rodeo RLP-5, Trade Winds: NewJbundland iii Song; the single was Rodeo Ro-147.

17. Rodeo RLP-7, Down to the Sea Again. I base the term "key text" upon the ideas of Sam Richards, set forth in his "Westcountry Gipsies: Key Songs and Community Identity," in Michael Pickering and Tony Green, eds., Everyday Culture: Popular Song and the Vernacular Milieu (Milton Keynes: Open U Pr, 1987): 1 25-49.

18. Rodeo Ro- 156. For Simani, see Gerald L. Pocius, "The Mummers Song in Newfoundland: Intellectuals, Revivalists and Cultural Nativism," Newfoundland Studies 4 (1988): 57-85.

19. Rodeo Ro-l5l.

20. Rodeo Ro-l60. My comments on "The Badger Drive" are based on John Ashton's unpublished study. Information on "The Business of Making the Paper" comes from Omar Blondahl and John Maunder.

21. Rodeo RLP-34, . Visit to Newfoundland.

22. Banff RBS- Il 73, The Great Seal Hunt of Newfoundland, reissued as Rodeo RLP-80, Songs of the Scalers.

23. Jamieson interview; See Paul Mercer and Mac Swackhamer, " 'The Singing of Old Newfoundland Ballads and a Cool Glass of Beer Go Hand in Hand': Folklore and 'Tradition' Newfoundland Advertising," Culture& Tradition 3(1978): 36-45.

24. Banif RBS-1 142, Roving Newfoundlander, and Arc A-537, Songs of Sea and Shore, are both dated by Michael Taft as being recorded in 1959. A seventh and final album of Newfoundland songs, Melbourne AMLP-4007, Once Again for Newfoundland, was dated by Taft as from 1967; according to Blondahl (letter to author, 3/17/91) it was recorded in 1964. Four other albums of folksongs on the Banff and Arc labels also included a few Newfoundland songs. Subsequently songs from the original albums were reissued on three albums devoted to Blondahi as well as on six anthologies.

Résumé: Neil Rosenberg décrit la carrière d'Omar Blondahl, interprète de chansons traditionneles, qui est venu a St. Jean, Terre-Neuve, en 1955. Pendant dix ans, ii chantait des chansons terreneuviennes a la radio et la television, et a connu une rande réussite avec ses disques. Il était le premier chanteur professionel a se spécialiser dans les chansons traditionnelles de cette province, et était responsable de l 'introduction de la guitar comme instrument d 'accompagnement.

© Canadian Journal for Traditional Music

No Comments