Mapleoak

Websites:

https://www.terrascope.co.uk/MyBackPages/Maple_Oak.htm

Origin:

Toronto, Ontario, 🇨🇦

Biography:

Mapleoak by Nick Warburton

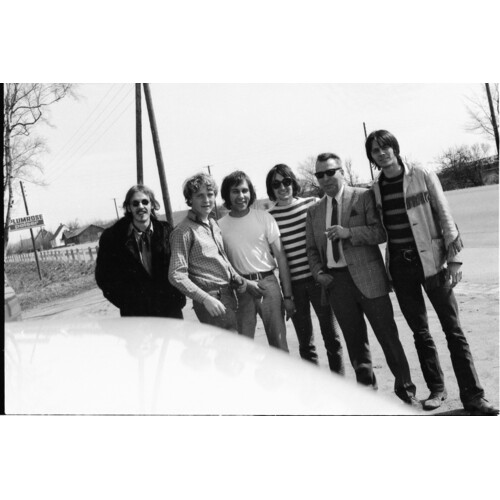

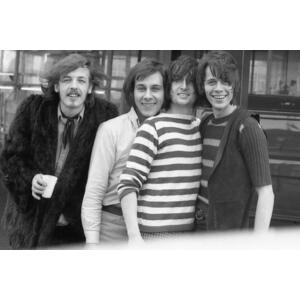

The first real inkling Ray Davies had that Peter Quaife (b. 31 December 1943, Tavistock, Devon, England) was serious about leaving The Kinks was when someone drew his attention to an article in the centre spread of NME magazine and its headline: "KINKS SPLIT - says Peter Quaife". The story, which appeared in the issue ending the week 5 April 1969, included a smallphoto of Quaife sitting contentedly on Hampstead Heath with three unidentified musicians. To say it was a shock to Ray Davies and the other Kinks would be an understatement. To Quaife, however, the separation was something he'd been planning for sometime.

Four months later, and half a world away, the Toronto Telegram ran an expose on Quaife's new band and the reasons behind the bass player's shock departure. In the article "A place to stay in England", Quaife spelt out his dissatisfaction with The Kinks and his reason for leaving. "I hadn't been happy with The Kinks for well over a year before I split," he told journalist Bill Gray. "For one thing we just never played anywhere. Ray Davies hates live shows, hates touring, so most of the time, we just sat around at home collecting our royalty cheques. It was an easy life but not a very fulfilling one."

For Quaife, who'd grown up watching his childhood friend take over every aspect of the band's running, from writing and arranging all of the material to singing all of the songs and doing all the talking, there was no opportunity for him (or the other Kinks) to express themselves. "I felt totally stifled under those circumstances and finally had to get out."

The Toronto newspaper's interest in Quaife's new project was understandable given that The Kinks were one of the most respected British Invasion groups. But that is only part of the story. At closer inspection, it revealed Quaife's unnamed group to contain a number of local musicians who had "cut their teeth" on Toronto's vibrant rock scene before moving to the UK (as it turned out literally a few days before the NME photo shoot).

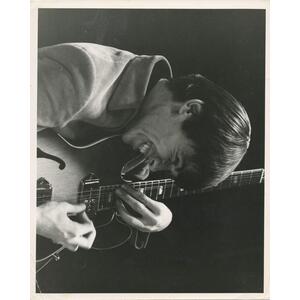

Child actor, turned musician Stan Endersby (b. 17 July 1947, Lachine, Quebec) had been playing lead guitar professionally in Toronto since the early 1960s, most notably with local R&B outfit, The Just Us. Over the course of the next three years, Endersby worked extensively on the local scene, remaining with the group as it morphed first into The Tripp and then Livingstone's Journey.

When the group foundered in the early months of 1968, the young guitarist decided to leave Canada and check out the music scene in England. Endersby's father was English and had been in the RAF during the war. Flying to London that spring, Stan stayed with his brother Clive, an aspiring actor, who had appeared in Mickey Spillane's "Girl Hunters" among others and was doing a lot of television work for the BBC.

"It was really amazing because I hadn't seen my brother in about six years and he sounded totally English," Endersby told this author in an interview for Ptolemaic Terrascope in 2001. "It was around eleven o'clock at night and I told him I was going out to see what was going on. He warned me that everything was closed but I went out anyway. I remember walking around Piccadilly Circus and I heard this music coming from this club called Hatchettes."

As he was walking past the club, Endersby remembers the owner mistaking him for an American. Embarrassed by his error, the club owner invited Endersby into the club, sat him in the VIP section and bought him a drink. He soon realised that Endersby was a musician and after Endersby asked if anyone ever sat in with the house band, the club owner stood up and told the musicians to let him sit in.

"When I finished this guy comes up to me and says: 'My name's Bill Fowler and I am from the Arthur Howes agency'. He said Peter Quaife of The Kinks was there and wanted to have a word with me."

Quaife, who recalled the Hatchettes meeting in the Bill Gray interview for the Toronto Telegram, says that Endersby immediately stood out. "I'd been looking around for a couple of months for someone who would fit into my conception of a group, but I was really getting nowhere until one night I saw Stan gigging on guitar with this terrible band. What he was doing really knocked me out, so I introduced myself and we started talking and found that we had a lot of the same ideas."

Endersby recalls Quaife asking him to call round at his place in Muswell Hill the next day to discuss his plans for the new group. "He said he was unhappy with The Kinks and was thinking of leaving the band," explains Endersby. "He asked me if I would be his lead guitarist and singer in a new band. I didn't really know if I was going to stay in England or go back to Canada, but I was interested in the idea."

Quaife had contractual obligations to fulfil with The Kinks so over the next couple of months, Endersby hung around London, picking up live work here and there.

Playing with the likes of Horace Faith's soul band, Endersby made enough money to get by but decided to return home to Toronto that autumn and wait for Quaife's call. He immediately landed on his feet. Commissioned to write the soundtrack music to an American TV show called The Cube, which was being filmed at CFTO for NBC and produced by future Muppets creator, Jim Henson, Endersby cast about for suitable musicians to help out.

His first thoughts were of two talented players that he had known for years from the local scene - keyboard player Marty Fisher (b. 26 December 1945, Vancouver) and drummer Gordon MacBain (b. 5 August 1947, Toronto). Both had worked together since 1964 in local bands, Bobby Kris & The Imperials and then Bruce Cockburn's short-lived outfits, The Flying Circus and Olivus. The threesome clicked well on a musical and personal level.

The project, however, was only a stopgap. With the recording finished, Endersby played a couple of dates with a local group called Leather before replacing future Chris de Burgh guitarist Danny McBride in Transfusion, the house band at Toronto's top club, the Rock Pile in January 1969. The following month, the band assumed the name Crazy Horse (not to be confused with Neil Young's backing group) and played one of its most notable shows, opening for Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention on 23 February. A month later though, a more attractive option landed on the table.

Pete Quaife had fulfilled his obligations with The Kinks and was intent on putting a new band together with his Canadian friend. "I got a call from Peter saying he was leaving The Kinks and to come over," remembers Endersby. "He sent my fare and I brought Marty (Fisher) with me."

On April Fool's day, Endersby and Fisher arrived in London to join Quaife and English drummer Mick Cook (who may have been the same guy who was in The Blue Rondos and later Home) in the new group. Quaife's outfit was revealed to the world in NME's centre spread less than a week later and was a complete surprise to the other Kinks, who were unaware of their bass player's musical plans.

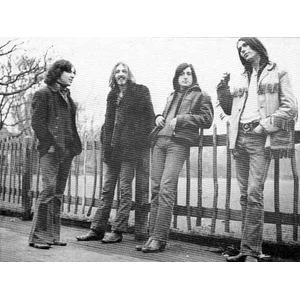

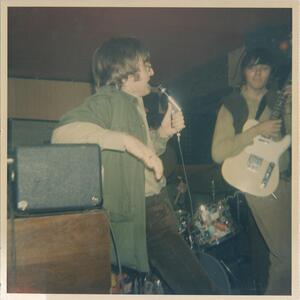

MapleoakAdopting the name Mapleoak (a combination of the two countries' national emblems - the Canadian Maple Leaf and the English Oak), the quartet quickly rehearsed at the Marquee and the Angel Pub in north London and then played one of its earliest shows at the Factory in Birmingham on 5 May.

Thanks to Quaife's contacts in Denmark, the group landed a month's work in Copenhagen, playing at venues like the La Carousel. "That's where the guys had the big beer mugs and they used to smash them on the dance floor," laughs Fisher looking back. (Endersby remembers seeing them eating glass too!)

It was a great experience for everyone except Mick Cook, who was given the elbow before the band's return to England in June. "Mick got a little crazed with the whole thing," explains Fisher. "He was nice though. He let us stay at his place for a bit when we first arrived. He hooked up with some girl in Denmark and was going to stay."

Looking around for a new drummer, Endersby and Fisher had only one person in mind - Gordon MacBain. "It seemed an obvious choice because I had worked with both Marty and Gordon on The Cube," explains Endersby.

Since the TV show, MacBain had enrolled at art school and was starting to write songs. To make some money, he had also agreed to take part in a reformed Bobby Kris & The Imperials and had just finished a series of gigs at the Night Owl, running from 19-21 June, when the call came from England.

With MacBain onboard, Mapleoak received some firm offers of a recording deal - one from Liberty Records and the other from Decca. While the group chose to go with Decca, Fisher rues the decision to turn down another offer made by Island Records, which he believes would have been better in the long run. "Muff Winwood came to see us and really liked the band. He said, 'I can't give you much of an advance but we can help with equipment and give you all the time you need in the studio'."

MacBain agrees with Fisher's assessment. "That was probably the turning point in the whole Mapleoak saga. [Personally] that was the biggest mistake we made. Muff Winwood was a superb guy and he loved the band. He wanted to really develop us. He had lots of ideas and he was a real hands-on guy. Decca - they couldn't have cared less, they didn't give a damn. You know, it was like, 'Okay, these guys have got Peter Quaife in the band, give them some money, throw them in the studio and see if anything happens'. [Not going with Island] was the most stupid thing that we could have done. I regret it to this day."

At this stage, the group's repertoire was fairly diverse, mixing recently composed band originals with covers of material by Bob Dylan, The Band, Tim Hardin, John Sebastian and fellow Canadian, Bruce Cockburn, who had played with Fisher and MacBain in the aforementioned Flying Circus and Olivus.

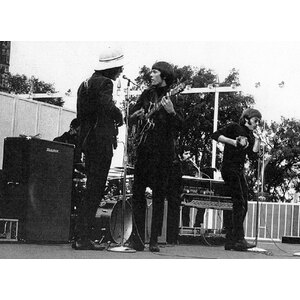

The group was popular with audiences and during the latter part of 1969 Mapleoak found a steady stream of bookings both on the continent, where they played in Brussels and Antwerp in Belgium and Amsterdam in the Netherlands, and also in the UK.

During this period, Mapleoak appeared at the Marquee on Wardour Street, sharing a bill with Keith Relf's post-Yardbirds band, Renaissance. "I [also] remember hearing James Taylor [there]," says Endersby. "Peter said there was this American guitar player that wanted to check out Stonehenge so we heard him play (probably on 15 June). He was wonderful and we went to Stonehenge. We took him out in our Cummer van and his songs just blew me away."

Mapleoak also played at the Roundhouse every Saturday afternoon. "Elton John was playing there at the time and he was a nobody," remembers MacBain. "We used to see his little bus parked with the name plate on the front that said, 'Elton John' and we used to think it was a band."

"Ginger Johnson, a South African guy, would play and his band was fantastic," adds Endersby. "I think he did all the drumming on The Stones' 'Sympathy For The Devil'. We really enjoyed playing with his group. We also played with Curved Air and J. J. Jackson."

MacBain remembers playing at the Speakeasy on one occasion and also performing at the London Palladium on a bill featuring Matt Monroe and Roger Whittaker, which according to Fisher was televised. "They told us we couldn't talk in between songs or introduce songs or anything like that," says MacBain. "You were supposed to go on stage, play your songs and then get off. First thing we did when we got up there was I said, 'Hi everybody, this is a song called...' and the producer was over in the wings jumping up and down."

In early 1970, the group entered Decca's Hampstead studios, abetted by manager Derek Cooper and engineer Mike Hutson, to record some material for a prospective single. For some unknown reason, some of the songs, including a cover of Bruce Cockburn's "Morning Hymn" and "Flying Circus", which Fisher and MacBain had originally performed when they were with Olivus, were subsequently canned and remain unreleased to this day.

Two tracks were earmarked for release and on 3 April 1970, Decca released Mapleoak's lone single, which coupled MacBain's rousing "Son of A Gun" with Endersby's "Hurt Me So Much". It was a promising start but then the single sank without a trace. "[Son of a Gun] wasn't getting played," points out Fisher. "It may have had something to do with a gig we played at one of the top clubs in London, a place to be seen. The biggest DJ in England was there and Peter Quaife made some insulting remark - 'the audience wouldn't appreciate the music we're playing' or something like that. It was really a bad thing to say. I walked out in disgust.

"Peter was losing interest when the single didn't take off," continues Fisher on the bass player's sudden departure from the band in the summer of 1970. "Peter thought for some reason that it was going to go on the charts but it didn't. [He] said, 'Well nothing's happening'. Peter was losing his flat. He'd already sold his car and he wasn't able to keep up the payment on his combo that he'd bought."

Reduced to a trio, and with Fisher providing the bass parts on the keyboards, the band began sessions for an album at Decca's Hampstead studio. The experience proved to be a major disappointment.

Fortunately, the group had signed a publishing deal with UA and Mike Hutson set the band up to record at De Lane Lea studios in Dean Street where they completed the album under the guidance of engineer John Stewart.

While Marty Fisher was pretty pleased with the album's final production, he remained critical of the rest. "It's not strong enough," he complains. "The writing's not strong enough [and] none of us were really strong singers at the time."

"The album didn't really work," adds MacBain. "One song that really gelled on that record was 'Sail Away' and it cooked. "Flying Circus" and "Frankly Stoned" were good but some of the other stuff was substandard. We didn't have enough time, we were young and inexperienced."

MacBain feels that things would have been a lot different if the band had gone with Island in the first place. "It probably would have been a lot better than it was if we had had someone like Muff Winwood steering the ship because he would have said, 'Hey, you know what guys that doesn't make it or hey run with that, that's good, go in that direction'. Because he knew, he was a musician, obviously a very brilliant musician/producer and he would have been producing us."

While Endersby chips in with the opening number "Guitar Pickers" and Fisher contributes "All These Times", MacBain pens most of the original material. Band associate Mike Hutson meanwhile contributes "Down Down".

With the recording complete, the band awaited its release but Decca, with no explanation, postponed it for several months. Finally, it appeared in early 1971, and is arguably one of the first (if not the first) country-rock albums to be recorded in England.

Together with the band's original material, which for some inexplicable reason didn't include the two sides of the single, the album also contains a number of Bruce Cockburn and Bill Hawkins's songs from Fisher and MacBain's time with The Flying Circus, including "Frankly Stoned" and "Flying Circus".

By the time the album appeared, however, the group had returned to Toronto, and, following a few dates at the Night Owl, broke up. Fisher subsequently jobbed around with various local artists and then fronted his own band, Meltdown before dying from a heart attack in August 2005.

A year before his death, Fisher spoke fondly about his Mapleoak experience, noting that "England was great but it was a scuffle." However, he has no doubts about why Mapleoak never broke through. "Decca Records didn't put any financing behind [the album] and the manager just took all the money we did get; money that should have been spent on promoting the band. He bought a TV and new curtains for his house but we were starving to death. When I came home back from England I weighed 114 pounds. I looked like I was from Biafra. People thought I was a heroin addict."

MacBain agrees with his assessment of the band's manager. "Basically, I think what he did was he saw Peter Quaife as a cash cow and filled his head full of dreams and delusions and took him away from The Kinks. In my opinion at the time, I thought it was like leaving The Beatles to go join the band up the street."

Following Mapleoak's demise, Endersby went solo before playing with Rick James's Heaven and Earth. Over the next few years he played with a number of Toronto groups, including The Village with Keith McKie and Bruce Palmer before heading to Los Angeles and working with former Love guitarist Bryan MacLean among others. During the mid-1980s he toured with Buffalo Springfield Revisited and later recorded with the legendary Toronto blues band, The Ugly Ducklings. He is currently recording his own material.

MacBain found work playing with a number of local groups. More recently, he has developed his song writing skills and has put his songs forward to a number of artists, including Chris de Burgh and Aaron Neville. He is waiting to hear back on whether any of his songs will be recorded.

Peter Quaife, who moved to Denmark after splitting from Mapleoak, later relocated to Belleville, Ontario where he worked as an airbrush artist. In 2005, he moved back to Denmark and continues to paint.

A year before, Decca in Japan had issued the Mapleoak album on CD, although it chose not to include the single in the package. While the release highlights the growing interest in the band, it also underlines the need for a comprehensive package, bringing together all of the group's recorded output together with detailed liner notes and photos. Hopefully, this article will be a step in that direction.

Many thanks to Stan Endersby, Marty Fisher, Gordon MacBain, Mike Paxman, Carny Corbett, Ptolemaic Terrascope.

© Copyright Nick Warburton, November 2006

To contact the author, email: Warchive@aol.com

Canadian guitarist Stan Endersby remains an unsung hero in rock music circles. Over the last forty years, he has played a supportive role for some of rock’s most respected artists, including Motown funkmeister Rick James and Love’s Bryan MacLean. Endersby has also worked with former Kinks bass player Peter Quaife and been a member of the Buffalo Springfield tribute band, Buffalo Springfield Revisited. He is currently a distinguished member of Toronto garage legends The Ugly Ducklings. Formerly a child actor, Endersby (b. July 17, 1947, Lachine, Quebec), began his career in the early ’60s with The Omegas, best known for containing future Toronto rock promoter John Brower. Endersby’s tenure was short-lived and he quickly moved on to join C J Feeney & The Spellbinders, a local rock ‘n’ roll band led by former Jack London & The Sparrows keyboard player C J Feeney. (The Sparrows, after numerous personnel changes, ultimately evolved into heavy rockers Steppenwolf).

In late 1965, Endersby and bass player Wayne Davis accepted an offer to join the promising rock outfit, Just Us, led by singer/bass player Neil Merryweather. Merryweather (real name Neil Lilley) had hatched the band a year earlier with keyboard player Ed Roth and drummer Bob Ablack, and the original line-up recorded a lone single “I Don’t Love You/I Can Tell” for the Quality label. Though no recordings were made as such, The Tripp did appear in the first episode of CBC TV’s “Sunday Show” and continued to be a regular fixture on the Toronto club scene. In early 1967, former Richie Knight & The Mid-Knights pianist Richard Bell briefly augmented the group but he soon moved on to play with Ronnie Hawkins (and later Janis Joplin’s Full Tilt Boogie Band). Around the same time, Jimmy Livingston made a guest appearance on local rivals Mandala’s album, “Soul Crusade”.

During the summer, Neil Merryweather dropped out to briefly join Ottawa singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn‘s new psychedelic outfit The Flying Circus, before launching his own group later in the year. The remaining members soldiered on, recruiting former Luke & The Apostles and Simon Caine & The Catch bass player Dennis Pendrith, and changed name to Livingston’s Journey.

Though rather short-lived, the Journey were undoubtedly one of Toronto’s most colourful and experimental groups. No studio recordings were ever made, although group originals like “Inner City” and “Bull Feathers”, and a heavy version of The Beatles’ “You Can’t Do That” were later captured live and only hint at the potential of this unique group. The group also attracted a great a deal of media attention – disrupting business in downtown Toronto in August 1967 while entertaining fans at the city’s Esplanade (a plaza on the ground floor of the Richmond-Adelaide Centre), and through appearances at Ottawa’s Mall and Parliament Hill the following month. Soon afterwards, however, the band began to unravel – Ted Sherrill came in on drums from The Vendettas and former The Imperials frontman Bobby Kris was drafted in to replace Livingston, who had become increasingly unreliable. The final line-up struggled on for a few months and in the spring of 1968 played its final date at Toronto’s Night Owl (which was recorded on tape by Endersby’s brother but never released). Pendrith was first to jump ship, replacing Neil Merryweather (again) in Bruce Cockburn’s new project, Olivus. While Roth, headed to L.A. to join the ranks of Merryweather’s new band, Endersby traveled to England to visit one of his brothers, and on his first evening was introduced to Kinks bass player Peter Quaife at the club, Hatchettes. Sitting in with the house band, Endersby’s guitar playing impressed many of the club’s regulars, including Quaife who told Endersby that he was thinking about leaving The Kinks and forming a new group. Over the next few days, Endersby and Quaife made tentative plans to forge a musical partnership, but the project was put on hold when Quaife decided to postpone his departure from The Kinks. Over the next six months, Endersby jobbed around London with various local groups, including Horace Faith’s soul band before heading back to Toronto in the autumn of 1968.

Back in Canada, he provided the music to an American TV show called “The Cube”, which was produced by Jim Henson (later of the Muppets’ fame). The studio band incidentally, also included former Bobby Kris & The Imperials members Marty Fisher and Gordon MacBain, both of whom had also worked with Bruce Cockburn in his recent bands The Flying Circus and Olivus. With the recordings complete, Endersby briefly hooked up with the house band at Toronto’s famous rock venue, the Rock Pile, but in early 1969 received a phone call from Quaife who was now ready to put the promised band together.

On April fool’s day, Endersby (and Marty Fisher) arrived in London to join Quaife and English drummer Mick Cook in a new unnamed group. Quaife’s outfit was revealed to the world in the centre spread of Britain’s NME magazine 2 days’ later in a move that reportedly surprised the other Kinks members who were unaware of Quaife’s extra curricular activities. After adopting the name Maple Oak (a combination of the two countries’ national emblems – the Canadian maple leaf and the English oak), the quartet quickly rehearsed at London’s Marquee before embarking on a month-long tour of Denmark. Returning to the UK, Cook dropped out and Fisher’s mate Gordon MacBain flew over from Toronto to fill the drum stool.

Maple Oak signed a deal with Decca Records soon afterwards and began recording in earnest at West Hampstead studios. Musical differences with a studio engineer however, resulted in the group taking the recordings to De Lane Lea studios where sessions were completed for a debut single coupling MacBain’s “Son of a Gun” with Endersby’s “Hurt Me So Much”. Any musical aspirations that may have existed were soon dashed when Decca delayed the release of the single for over six months. Dismayed by the public’s response, the lack of gigs and record company support, Quaife lost interest in the project and dropped out before the single’s release. Reduced to a trio, and with Fisher providing the bass parts on the keyboards, Maple Oak returned to De Lane Lea studios to record a new batch of songs that bore little resemblance to the gritty blues-rock featured on the single. Without a hit single to promote the album (neither side of the single was included on the record), Decca decided to postpone the release of “Maple Oak” until early 1971, by which point the group had returned to Toronto and the members had gone their separate ways. Despite its rarity and unevenness, the album is probably one of the first country rock-influenced records to be made in England (it even bares a slight resemblance to fellow Canadians The Band) and contains a number of early Bruce Cockburn songs, which the writer never recorded himself.

Back in Toronto, Endersby briefly entertained thoughts of a solo career but decided instead to launch a new band. During his stint in England, he had befriended producer John Stewart, who had worked with the likes of The Bee Gees, Deep Purple and Lulu among others. Endersby had encouraged Stewart to move to Toronto and when the producer followed his advice and found work at Eastern Sound studios, Endersby approached him to produce a new band he had recently put together, later to be dubbed Heaven and Earth.

The studio-bound outfit also included ex-Paupers bass player Denny Gerrard, former Luke & The Apostles drummer Pat Little and Endersby’s old Livingston Journey colleague Ed Roth (keyboards). As sessions proceeded, former Mynah Birds singer and future Motown soul star, Rick James turned up in the studio and took over the project. With James at the helm, Heaven and Earth proceeded to cut about an album’s worth of material, but ultimately only two singles finally emerged – “Big Show Down/Don’t You Worry” and “You Make The Magic/Rip Off 1500”, issued on RCA Victor in late 1971/early 1972. The band fell apart soon afterwards when James took off with the tapes and re-recorded some of the tracks with his next project Great White Cane.

Endersby meanwhile moved on to join a number of local outfits including Buckwheat Noodle, Diamondback and the Village (the latter alongside former Kensington Market singer/songwriter and guitarist Keith McKie and ex-Buffalo Springfield bass player Bruce Palmer). No recordings were made, but the group attracted a modicum of media attention for its live dates in Toronto’s Yorkville area.

Relocating to Los Angeles in the late ’70s he became fully immersed in the new wave scene, and it was during this period that he teamed up with former Love singer/songwriter and guitarist Bryan MacLean in the Bryan MacLean Band alongside Maria McKee. A number of recordings were reportedly captured on tape, but none have so far seen the light of day.

Endersby subsequently toured with original members Bruce Palmer and Dewey Martin in the Buffalo Springfield tribute band, Buffalo Springfield Revisited during the mid-’80s, appearing on a cover of Neil Young’s “Down To The Wire”. After several years on the nostalgia circuit, he returned to Toronto and briefly dropped out of performing. Taking up bass for the garage legends, The Ugly Ducklings in the late ’90s, Endersby made his debut at the Toronto Rock Revival concert, held at the Warehouse on May 2, 1999. Besides gigging sporadically with the band, he has recently played on the group’s first studio recordings since 1980’s “Off The Wall”.

While Endersby’s profile in recent years is arguably greater than it has ever been, interest in his early career has grown steadily. Last year, the Maple Oak album was finally issued on CD, complete with the non-album single. A recent article on Maple Oak in the British magazine Ptolemaic Terrascope has also sparked interest in his early career and will hopefully lead aficionados of that period to discover Endersby’s recordings with Livingston Journey, Heaven and Earth and Bryan MacLean.

With notes from Stan Endersby