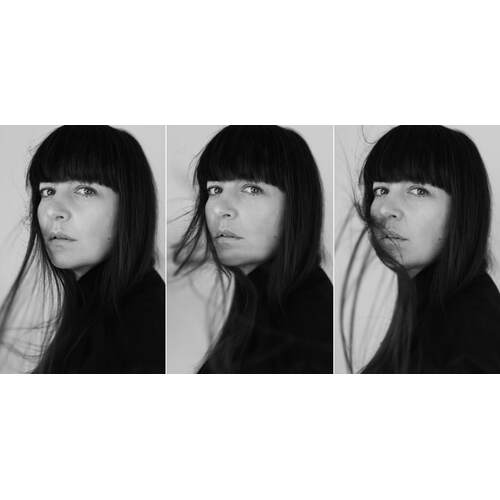

Yorke, Alanah

Websites:

http://www.alanayorke.com/

Origin:

Mount Uniacke, Nova Scotia, 🇨🇦

Biography:

"Sounding like a drifting daydreaming Florence and the Machine or a mystical Cat Power, Alana Yorke has a rawness in her voice that sits upon the enchanting, dark fairy tale music of her debut album Dream Magic."

-Shades of Cool Magazine (London, UK)

Even with your head above water, it can be hard to determine where the sky ends and the sea begins on an overcast day. Waves mirror the slate-grey clouds; fog renders the boundary between air and brine as hazy as thumb-smudged charcoal. And that’s without a complete immersion. Duck down, and it’s even more disorienting. You can make out beams of refracted light, ascending bubbles, the muffled ambient vibrations of sound waves. Floating under the surface, you’re forced to reorient yourself.

For Alana Yorke, that in-between zone is a space of transformation. It’s the guiding concept behind her latest album, Destroyer, an art-pop stunner that represents both a creative triumph and the culmination of a gruelling multi-year process in the Nova Scotia musician’s life and career. From its genesis, says Yorke, Destroyer was anchored in the idea of a solitary descent to face the self and come back wholly changed. In the artist’s case, this passage was both personal and oceanic, both metaphorical and painfully concrete.

In November 2022, Yorke woke up one morning and realized she was unable to move her left arm. A few days (and numerous hospital tests) later, she discovered she’d had a hemorrhagic stroke that affected the right hemisphere of her brain (associated with creative expression) in the parietal lobe (responsible for receiving and filtering sensory input). What could have been an unmitigated disaster changed Yorke’s life. The previous decade had been filled with profound challenges — during a sample-gathering scuba expedition as part of her academic work, she ran out of air and subsequently developed debilitating PTSD. The stroke, however, was a serendipitous force: the psychological heaviness suddenly lifted, and Yorke found herself freed from past emotional baggage and propelled by euphoric creativity. While the album that became Destroyer had always been part of a process of plumbing the depths, Yorke was consumed by a desire to share what she had experienced on the other side of the veil. “The goal was to bring these images and stories back to our world,” she explains.

In Yorke’s case, music has always been a foundational mode of connection. Before she could write out sentences, she intuitively knew how to express herself through song. At age four or five, she would sit at the piano, a prodigiously talented preschooler picking out the black and white keys that would allow her to translate her innermost feelings into melodies. As Yorke grew older and grappled with the complexities of coming of age in a small village on Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy, music became as much a mode of survival as it was a form of creative expression. Over time, she found new tools — guitar, vocal timbre and tone, the subtleties of lyrics, the power and nuances of production — and discovered she had a knack for distilling those emotional missives into dreamy, percussive hooks. To this day, Yorke’s songs hold the function they did for her as a child: they’re portals to share experiences that can’t be contained in language, outlets for conveying a particular mood or dream or reflection. This is the universe of Destroyer, created in collaboration with her creative and life partner Ian Bent (a fellow Nova Scotian musical child prodigy), where those snapshots of Yorke’s psychic landscape are fanned out against a layered musical backdrop coloured by a 21-piece string orchestra, the ultraviolet cool of ’80s synth-pop, the austere grace and rhythmic cadences of minimalist contemporary composers and the whole-hearted reverberation of anthems that call forth echoes from the unconscious, somewhere between the tidal forces of Kate Bush and Philip Glass.

On Destroyer, Yorke transforms epiphanies and upheavals from her singular experience into glimmers of universal resonance. An encounter with a spirit guide informed the wistful “Léa”, a piano-led existential push-pull in which a glorious tonal shift around the midway mark lets us share in a life-changing revelation. “All the Flowers” began as a meditation on how personal grief can feel infinite in scope, then evolved into a reflection on collective mourning after the death of David Bowie — the orchestral arrangement feels both elegiac and cathartic; the stuttering percussion conjures echoing heartbeats.

As Yorke notes, capturing these world-altering experiences was itself a form of alchemy. If Destroyer began from a place of disorientation, she and Bent braved rings of fire to arrive at their ultimate vision. The first, Yorke says, involved grappling with the overwhelm of PTSD; the second was eking out the album. “It tested me so completely,” she notes. “We had to become different people to rise to the expectations of the work.” The stroke, finally, served as the third ring of fire — and in moving through those flames, Yorke underwent a phoenix-like metamorphosis. Now, as she rises above the surface, Destroyer has become an offering from the depths. “I was motivated to make something beautiful from such excruciating experiences,” she says, “so that I could help others to not have to go through that alone.”